Taixu 太虛 was one of the most influential thinkers of modern East-Asian Buddhism. In 1904, at the age of 14, he became a monk at Xiǎo Jiǔhuá temple 小九華寺 in Suzhou, China. Soon after, he developed an interest in modern science, left-wing politics, and Buddhist reform. A decade later (partially due to changing political circumstances) he had himself sealed in a cell in a monastery to study Buddhist scripture and philosophy. After he left his cell in 1917, he revived a Maitreya Pure Land cult, but also continued working for the modernization and revival of Buddhism in China under the header of Rénjiān Fójiào 人間佛教, which can be translated as “Buddhism for the human world” or “Humanistic Buddhism”.1 Taixu was critical about the way Buddhism had been (ab)used by rulers and aimed to create a “Pure land in the human world” 人間淨土. “In the past,” he wrote, “Buddhism was used by emperors as a tool to fool people with ghosts and gods, but in the future it should be used to study the universal truths of life to guide the development and progress of the people of the world”.2

Through his disciple Yinshun 印順, who fled to Taiwan in 1952, Taixu’s Rénjiān Fójiào 人間佛教 eventually reached Vietnam, where Thích Nhất Hạnh translated the term as Nhân gian Phật giáo, which was translated into English as “Engaged Buddhism” in turn. While this is probably the most noticeable legacy of Taixu and Yinshun from a Western perspective, it is hard to overstate the influence of Yinshun and Humanistic Buddhism on contemporary Taiwanese Buddhism. During the “White Terror”, a period of martial law that lasted from 1949 to 1987 (or 1992), Humanistic Buddhism was active in charity work, but after the end of martial law, more activist variants of engaged Buddhism emerged in Taiwan. Humanistic Buddhism aimed to create “a Pure land in the human world” through moral education mainly, but for these activist Buddhists that was insufficient. Creating a Pure land in the human world also required environmental protection, socioeconomic reform, and cultural change.

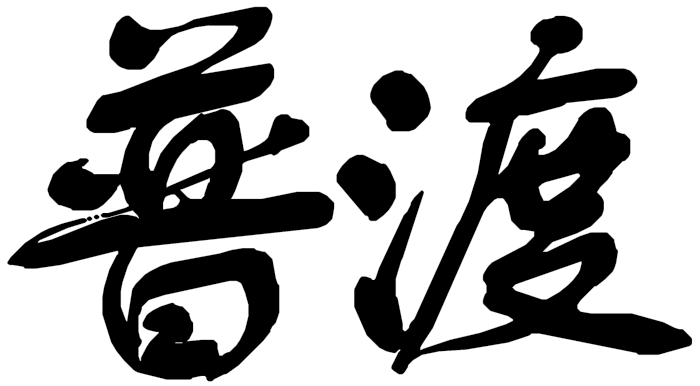

In an interview published in the first regular3 issue of the journal Buddhist Culture 佛教文化, which was the mouthpiece of this movement, Yang Huinan 楊惠南, a Buddhist scholar and student of Yinshun, distinguished two interpretations of “universal liberation” (普渡 pǔ-dù):

One is “mechanistic”: to develop the conscience of every sentient being to purify its heart and achieve liberation (渡) in great numbers is called the universal liberation of sentient beings. However, the problem is that this […] method of liberation does not necessarily enable everyone to develop their conscience. Therefore, there must be another level of universal liberation (普渡) — “organicistic” universal liberation:4 paying attention to the relations between sentient beings and sentient beings, there is no liberation unless it is the liberation of all people in a country, or at least most of them, in one stroke — it is a collective liberation. For example, working out wildlife laws and environmental protection laws, and even the establishment of a social welfare system are not [mechanistic] “self-liberation”, but are what I call “organicistic universal liberation”, because all of these liberate many people in one stroke. Believers in a Humanistic Buddhism should urge the government to care about these. […] The efficiency [of self-liberation or mechanistic liberation] is very low. What we should advocate [instead] is organicistic universal liberation, which is organized and collective, and which liberates everyone together/collectively, or at least most people, all in one stroke.5

Yang here suggests two important reasons why individual or autonomous “mechanistic” liberation is inefficient. The first is that not everyone has the capacity to achieve liberation by themselves, or even “to develop their conscience”. The second reason takes into account that we are social beings rather than isolated individuals and implicitly infers from this that it is more “efficient” to help many interrelated people achieve liberation together. The goal of Buddhism, therefore, should be universal liberation in this sense. Furthermore, Yang argues that the state should play a central role in making this universal liberation possible. Considering that universal liberation 普渡 is the traditional task of Bodhisattvas, this means that Yang is implicitly suggesting that the state should be like a Bodhisattva, at least to some extent. Both of these ideas — “organicistic universal liberation” (有機論式的普渡) and (implicitly) the state as Bodhisattva — depend on a fundamental conceptual shift that took place in Europe around the turn of the 19th century and that spread to East Asia in (roughly) the last quarter of the same century. Consequently, these are very modern ideas, which is part of what makes these ideas interesting. Moreover, these ideas may also have some radical implications (from a traditional Buddhist perspective, at least), which is further reason for scrutiny. Before we go there, however, there is a third point that should be noted and that requires some further attention. While Yang does not explicitly state what it is that people should be (collectively) liberated from, much can be gleaned from his examples of “organicistic universal liberation”: wildlife and environmental protection and a social welfare system. Clearly, the aim is not merely to address suffering or dukkha in a narrow sense as something like existential dread or the mental anguish associated with impermanence and loss. And neither is it merely the suffering of humans that matters. Rather, Yang’s interpretation of suffering appears to be very broad — universal liberation is also a liberation from poverty, for example. This broad interpretation of suffering/dukkha matters for the more fundamental questions related to the aforementioned two ideas or suggestion in the quotation by Yang. Consequently, I will discuss suffering/dukkha first, before discussing to the aforementioned conceptual shift (and its possible implications for Buddhism) and Yang’s “organicistic universal liberation”.

Both of these ideas — “organicistic universal liberation” (有機論式的普渡) and (implicitly) the state as Bodhisattva — depend on a fundamental conceptual shift that took place in Europe around the turn of the 19th century and that spread to East Asia in (roughly) the last quarter of the same century. Consequently, these are very modern ideas, which is part of what makes these ideas interesting. Moreover, these ideas may also have some radical implications (from a traditional Buddhist perspective, at least), which is further reason for scrutiny. Before we go there, however, there is a third point that should be noted and that requires some further attention. While Yang does not explicitly state what it is that people should be (collectively) liberated from, much can be gleaned from his examples of “organicistic universal liberation”: wildlife and environmental protection and a social welfare system. Clearly, the aim is not merely to address suffering or dukkha in a narrow sense as something like existential dread or the mental anguish associated with impermanence and loss. And neither is it merely the suffering of humans that matters. Rather, Yang’s interpretation of suffering appears to be very broad — universal liberation is also a liberation from poverty, for example. This broad interpretation of suffering/dukkha matters for the more fundamental questions related to the aforementioned two ideas or suggestion in the quotation by Yang. Consequently, I will discuss suffering/dukkha first, before discussing to the aforementioned conceptual shift (and its possible implications for Buddhism) and Yang’s “organicistic universal liberation”.

Suffering/dukkha

A “broad” interpretation of suffering/dukkha like Yang’s is a key characteristic of variants of engaged and radical Buddhism and contrasts with “narrow” interpretations of dukkha as a kind of mental anguish associated with (the realization of) impermanence. Advocates of a narrow interpretation sometimes reject broader interpretations as more or less “un-Buddhist”. For example, James Deitrick accuses engaged Buddhists of forgetting “the most basic of Buddhism’s insights, that suffering has but one cause and one remedy, that is, attachment and the cessation of attachment”.6 In contrast, when Joanna Macy asked learned Buddhist monks in Sri Lanka about the application of the Four Noble Truths to worldly suffering by engaged Buddhists, “almost invariably, they seemed surprised that a Buddhist would ask such a question — and gave an answer that was like a slight rap on the knuckles: ‘But it is the same teaching, don’t you see? Whether you put it on the psycho-spiritual plane or on the socio-economic plane, there is suffering and there is cessation of suffering’.”7

One of the most central doctrines of Buddhism (if not the most central) is the Four Noble Truths (4NT) found in the Dhammacakkappavattana Sutta (SN 56.11): (NT1) there is suffering (dukkha), (NT2) there is an origin of suffering, (NT3) there is the cessation of suffering, (NT4) there is a path towards the cessation of suffering. (Exact phrasings of the four noble truths differ, but are largely irrelevant here.) It should be fairly obvious that this doctrine presupposes that suffering/dukkha is bad (because why would there need to be a path towards its cessation otherwise?). The badness of suffering/dukkha could be considered the zeroth Noble Truth (NT0). The presumption of NT0 can also be found in Śāntideva’s Bodhicaryāvatāra, for example: “if one asks why suffering should be prevented, no one disputes that!”8 Suffering/dukkha is bad; no one disputes that,9 and consequently, dukkha needs to be overcome or prevented (or alleviated). But what exactly is dukkha ?

The Pāli term dukkha (Sanskrit: duḥkha; I will omit italics hereafter, except where the term dukkha is mentioned rather than used, as in this case) is translated as “suffering”, “pain”, or “unsatisfactoriness”, among others. The diversity of translations suggests ambiguity, but this is actually not a translation issue — the concept is not defined in the canonical sources, leaving considerable room for interpretation. Nevertheless, the Dhammacakkappavattana Sutta illustrates the first Noble Truth (NT1) by giving a number of examples of dukkha: “birth is suffering, aging is suffering, illness is suffering, death is suffering; union with what is displeasing is suffering; separation from what is pleasing is suffering; not to get what one wants is suffering; in brief, the five aggregates subject to clinging are suffering”.10 In as far as a definition can be gleaned from these examples, that definition seems to suggest a broad interpretation.

As mentioned, in narrower views, dukkha is simply a kind of unsatisfactoriness of life caused by an inevitably frustrated desire for permanence. In this view, dukkha is personal/individual and psychological or mental. It is a kind of stress more than a kind of pain. In broader views, on the other hand, dukkha includes this unsatisfactoriness, but also physical pain and worldly suffering. The narrow/broad spectrum is related (but not identical) to the scholastic classification of dukkha into three kinds. The most basic kind of dukkha is physical and mental pain, which may even include dissatisfaction, annoyance, boredom, and fatigue. The second, more subtle kind of dukkha derives from change and the impermanence of everything. Any gain, any achievement, any satisfaction, any positive sensation or emotion, and so forth only lasts for a brief while, leading to unhappiness and craving for more after it has drained away. The third, even subtler kind of dukkha results from the fact that this change and impermanence is fundamentally outside of our control because everything is (inter-) dependent or conditioned. Nothing is permanent and nothing is independent of causes, conditions, and other things, including we, ourselves. Dukkha in this third sense, sankhara-dukkha, is related to existential dread and to a general dissatisfaction resulting from the fact that things never are or can be as we expect them and as we want them to be.

The narrow interpretation effectively (re-) defines dukkha as simply this third kind, typically on the grounds that the second to fourth of the Four Noble Truths appear to be concerned only with dukkha in this third sense. The argument appears roughly to be that because the Buddha was really only interested in sankhara-dukkha, Buddhism is, by definition, only concerned with dukkha in that sense.11 But this argument raises two questions. What did dukkha mean for the Buddha? And if his concept of dukkha was broad rather than narrow, then why did he focus on just one kind of dukkha?

Dukkha or duḥkha is typically contrasted with sukha, meaning something like happiness, pleasure, or bliss. The etymology of both terms is uncertain and disputed, and some suggestions appear rather far-fetched. Hermann Jacobi suggested well over a century ago that the etymological, literal meaning of the two words is “well standing” and “badly standing”, and this remains the most plausible analysis I have seen.12 But in this case, etymology does not really tell us anything relevant.

A major difficulty in uncovering what dukkha may have meant to the Buddha is that Greater-Maghadan culture — that is, the cultural environment of the Buddha — had no writing at the time he lived. The oldest Indian texts are the Vedas, but those belong to Vedic culture, which later developed into Brahmanic culture, and there were significant differences between the Vedic/Brahmanic and Greater-Maghadan cultures. Hence, we cannot just assume that the Greater-Maghadan concept of dukkha was the same as the Vedic or Brahmanic concept. But at the same time, lacking other contemporary sources, there is not much else we can do.

Duḥkha does not occur in any of the four Vedas, and its opposite, sukha is rare as well and almost exclusively used in reference to chariots;13 but both terms occur in the Brāhmanas and Āraṇyakas, the next layer of Vedic texts, which predate the Buddha by a few centuries. In those,

the terms sukha and duḥkha are used with fair frequency, almost always together, and with a semi-technical psychological meaning. In these passages sukha and duḥkha are the experiences of the “body,” as “actions” are of the “hands,” and “sight” of the “eyes.” Buddhist texts never reveal an acquaintance with this technical usage but it no doubt was in the background of their descriptions of sukha and duḥkha as the characteristic experiences of man.14

Significantly, duḥkha in the Vedic sources is nothing like sankhara-dukkha; it is a much broader notion that is closer to “pain”, “suffering”, or “distress”. And the Pāli canon and Jain Agamas suggest that the Greater-Maghadan notion of dukkha was not a narrow notion either. In the contrary, the notion of dukkha encountered in those is usually suffering in the broad sense, including pain, sickness, sorrow, loss, and so forth, but also including something like existential dread. These texts were written down much later and are probably heavily redacted, but it would be hard to explain why redaction would have broadened the term’s meaning. If Buddhism is essentially concerned with sankhara-dukkha, as supposedly expressed in the doctrine of the Four Noble Truths, then one would expect redaction to narrow the use of the term dukkha in accordance with that core concern, and not broaden it. That dukkha was not narrowed suggests that it was not and should not be interpreted narrowly. (It is probably also significant that in Chinese sūtra translations and other East-Asian Buddhist text, dukkha is rendered as 苦 ku, which in general usage means suffering in the broad sense.)

Furthermore, the traditional biography of the Buddha does not suggest a narrow interpretation either. According to the Jātaka tales, the kinds of suffering the Buddha witnessed and that motivated him to become a śramaṇa were aging, disease, and death. The story is probably apocryphal, but it suggests that in the early Buddhist tradition the concept of dukkha and the kind of suffering the Buddha was concerned with was broad. Based on these considerations, it seems rather unlikely that the Buddha’s concept of dukkha was narrow. But then why did he focus on sankhara-dukkha?

Perhaps, he did not. Perhaps, the idea that he did is a misunderstanding. The point of the examples of dukkha following the statement of the first Noble Truth (NT1) in the Dhammacakkappavattana Sutta (see above) appears to be that life inevitably involves suffering, and if that is the case, then the remedy is obvious. If birth is suffering, as the sūtra explicitly claims, then the solution is no longer being born, and that is exactly the purpose of the Buddha’s “Middle Way”. Furthermore, rebirth is caused by karma, which according to the Buddha is accumulated by intentional or volitional action, and intention or volition depends on something like desire. Thus, the doctrine that became known as the Four Noble Truths may originally have been something like the following: (NT1) Life inherently involves suffering (in the broad sense). (NT2) New lives or rebirths are caused by intentional actions (karma) and thus by craving or desire. (NT3) There is a way to end suffering, namely, by eliminating karma and rebirth (i.e., new lives with new suffering). (NT4) That way is the “Middle Way”. If this interpretation is correct, then the Buddha was never specifically concerned with existential dread, sankhara-dukkha, or dukkha in some other narrow sense, but always with suffering in a very broad sense.

But this is not the only possible answer to the question. Perhaps, the Buddha did indeed focus on curing sankhara-dukkha. If the problem diagnosed in the first Noble Truth is suffering in a broad sense, however, (as the list of examples of dukkha suggests) then there must be a reason why only a cure is offered for dukkha in a narrow sense (i.e., for sankhara-dukkha), but as far as I can see, no explicit reason or argument is offered. This could imply that the Buddha was not aware of the narrowing of the notion of dukkha, which seems implausible, or that he did not see a need to mention a reason or argument for narrowing of the notion. The latter may have been the case if that reason or argument was too obvious to be considered explicitly in the cultural context. If cultural circumstances made many kinds of suffering seem like inevitable facts of life, then there was no point in trying to diagnose and remedy those. If life inevitably involves aging, sickness, death, and a variety of other forms and kinds of suffering, and there is, therefore, little if anything one can do about that, then it makes sense to focus one’s attention on a kind of suffering that can be remedied.

Other answers are possible, and it is also possible that the Buddha’s ideas about dukkha subtly changed during his long life. If we can trust his biography, the Buddha lived and taught for many decades after his awakening and it is rather unlikely that during this long period his views did not further develop. Nevertheless, regardless of what exactly the Buddha taught, available evidence does not suggest that his concept of dukkha was narrow (even if he appeared to focus on remedying just sankhara-dukkha or some related specific variety of dukkha in the narrow sense). Furthermore, throughout history, the Buddhist commitment to alleviate suffering has typically been understood as concerning dukkha in the broad sense as well. For example, In China, “Buddhist activities included road and bridge building, public work projects, social revolution, military defense, orphanages, travel hostels, medical education, hospital building, free medical care, the stockpiling of medicines, conflict intervention, moderation of penal codes, programs to assist the elderly and poor […], famine and epidemic relief, and bathing houses”.15, 16

One example (among many others) of a Buddhist thinker assuming a broad understanding of suffering/dukkha is Nichiren (日蓮, 13th century Japan). In his Establishing the Peace of the Country 立正安國論, his imaginary interlocutor asks Nichiren about the state of the world. “Famine and disease rage more fiercely than ever, beggars are everywhere in sight, and scenes of death fill our eyes. Cadavers pile up in mounds like observation platforms, dead bodies lie side by side likes planks on a bridge. […] [W]hy is it that the world had already fallen in decline […]? What is wrong? What error has been committed?”17 Nichiren’s answer was that after much research and contemplation he had come to the conclusion that the cause of all this worldly suffering was that the Buddhist sects, the government, and people in general had turned their backs on the Lotus Sūtra, and that, if only they would mend their ways and “embrace the one true vehicle, the single good doctrine of the Lotus Sutra […] then the threefold world18 will all become the Buddha land”,19 or in other words a Buddhist utopia or worldly paradise. And “if you live in [such] a country that knows no decline or diminution, in a land that suffers no harm or disruption, then your body will find peace and security and your mind will be calm and untroubled”.20

Given all we know about the history of Buddhism and Buddhist thought, it seems that dukkha has typically been understood in its broad sense. Its seems to me that the kind of narrowing associated with the claim that the Buddha, and by extension Buddhism, was (is) exclusively concerned with sankhara-dukkha or dukkha in the narrow sense (and therefore, that other kinds of suffering are irrelevant from a Buddhist point of view) is a relatively recent invention. I haven’t seen any research into this topic, but my hypothesis is that this narrowing is an example of secularization. The term “secularization” is used in reference to a number of only loosely related social and intellectual developments. The here relevant sense of “secularization” is “marginalization of religion to a privatized sphere”.21 Suffering in the narrow sense is entirely private, while suffering in the broad sense also explicitly includes many kinds of “public” or worldly suffering (disease, poverty, injustice, and so forth). The narrowing of the interpretation of dukkha is exactly a marginalization of Buddhism to a privatized sphere (and out of the public sphere).

The invention of the state and society

Above, I wrote that two important ideas suggested by Yang Huinan, namely, “organicistic universal liberation” and the state as Bodhisattva, depend on a fundamental conceptual change. This change, which was very much an intellectual and cultural revolution, took place in Europe around the turn of the 19th century in a period called the Sattelzeit23 by Reinhart Koselleck,24 and spread to East Asia in (roughly) the last quarter of the same century. The two most fundamental conceptual innovations of the Sattelzeit — at least in the present context — are the modern concepts of the “state” and “society” (as well as “the social” as a sphere or category a life in general).

The modern concept of the “state” refers to something separate from both the person(s) that rule (i.e., the ruler or rulers, king, and so forth) and (the collective of) the people (that are being ruled). This concept developed in Western thought during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries — with Machiavelli’s Il Principe (1532) and Thomas Hobbes’s Leviathan (1651) being among the most important landmarks in this development — although details of the concept’s history remain disputed.25 In any case, political thought before the invention of the concept of the “state” could only be in terms of kings or other rulers as persons, who ruled over their personal belongings, more or less as extended households. After Hobbes (and some further intellectual developments), political thought could focus its attention on the “institutions of government and means of coercive control that serve to organize and preserve power within political communities”.26

It did take some more time before this conceptual innovation — that is, this new way of looking at sociopolitical reality — was fully accepted, however, and in that transitional period further important developments took place. This was the aforementioned Sattelzeit, which lasted from roughly 1750 to 1850 in Germany (starting, perhaps, a bit earlier in France and England). Europeans living before the Sattelzeit were lacking many of the abstract social concepts that we are used to now — concepts like “society” and “culture”, for example. Some of the words were already in use, but they did not mean (exactly) the same things.27

The word “society” had been used widely for centuries in reference to small institutional units between the state and the household. Societies were social circles or (legally established) associations. From the middle of the 18th century onward, the term started to be used in combinations such as “political society” and “civil society” to refer to an understanding of the state and its citizens that was heavily indebted to social-contract theory. But only in the late 1790s did the term start to be used to refer to something distinct from the state and distinct from its old meaning as “association” (and related notions).28 So for example, when Karl Marx wrote in the winter of 1857–8 that “society does not consist of individuals, but expresses the sum of interrelations, the relations within which these individuals stand,”29 he expressed an idea that was (becoming) common at the time, but that would have been nearly incomprehensible a century earlier.

It is no coincidence that the modern concept of “society” was invented around this time, of course. Northwestern Europe was in the middle of the industrial revolution and due to technological and socio-economic changes societies in the traditional sense — that is, social circles or associations — were growing rapidly. Hence, the term “society” included ever larger groups of people. Nevertheless, this social change did not by itself lead to the invention of “society” as we now understand the term. Not even the conceptual/theoretical innovation of “civil society” by social-contract theorists was sufficient — a further catalyst was needed. That catalyst was political change at the end of the eighteenth century in France and its fallout throughout the rest of Europe. These political and intellectual developments lead to a watershed in political thought, although it must be kept in mind that this process took several centuries.30 Before this period, political thought — or what is read as political thought now — concerned the ruler(s) as person(s). It was (usually) about his rights and obligations, his personal characteristics and virtues, and so forth. It was about the good king. Political thought after this period — that is, modern political thought — is about political institutions, social obligations, and many other “things” that would have made absolutely no sense in a pre-Sattelzeit conceptual framework.

Reckoning with conceptual change (1) — the state

In Western political theory, it is customary to read “state” for “king” in pre-Sattelzeit texts. No one insists that the essence of Hobbes’s version of contractarianism is the necessity of a king — rather, his ideas are adjusted to our modern conceptual framework. In “Buddhism and the State: Rājadhamma after the Sattelzeit”, I suggested to do the same in case of Buddhist political thought and applied this to the Rājadhamma, a list of ten royal virtues or duties that occurs in the Jātaka tales.32 In the same way that most contemporary Buddhist thinkers — including the Dalai Lama, for example — no longer accept the Buddha’s beliefs in a flat earth and some related cosmological and/or geographical ideas that have been shown to be false by science, we can also “update” aspects of Buddhist sociopolitical thought and allow it to exploit new insights and ideas and further develop on the basis thereof. Disallowing a reading of Buddhist political thought in a post-Sattelzeit conceptual framework is forcing it to remain stuck in a pre-modern past and forcing it to be largely irrelevant in the modern world. When read overly literally, pre-modern political thought is largely irrelevant because it applies to kingdoms where kings have absolute power and subjects (and everything else) are effectively the king’s property. Although the recent rise of authoritarian regimes all over the world may suggest otherwise, political arrangements like these do not really exist anymore,33 and therefore, traditional rājadhamma, for example, has no application.

Moreover, there are two further reasons for reading Buddhist political theory in terms of a modern conceptual framework. The first is that it may be able to provide a theoretical basis for the implicit turn away from absolute monarchism in Buddhist thought from (roughly) the last decades of the 19th century. The second reason is the fundamental attribution error.

With regards to the first of these reasons, Matthew Moore has shown that the switch from a preference for absolute monarchy under a virtuous king (as advocated by all canonical texts) to republicanism was often pragmatic and rarely grounded in rigorous philosophical thought.34 He writes that

in the mid- nineteenth century the crisis of colonialism and globalization forced every Buddhist country to abandon monarchy and instead embrace some version of republicanism. Although the rationalizations of this change differed among countries, a common theme was the idea that, under the conditions of modernity, republican institutions could fulfill the ethical requirements for government as well as or better than monarchical institutions.35

Reading “state” for “king” in canonical and semi-canonical texts could provide support for democratic, republican government, which is essentially incompatible with those same texts if those are read overly literally — and in case of rājadhamma it does provide this support indeed.36

The fundamental attribution error is a cognitive bias that leads to an overemphasis on disposition and personality-based explanations of individual behavior and an underemphasis or oversight of situational and environmental factors. Psychological research has shown that what we do is much more influenced or determined by circumstances than by supposed character traits such as virtues. The fundamental attribution error is a serious problem for virtue-based accounts of what people do or should do, including ideal theories about virtuous kings. Whether a king acts virtuously may depend more on the circumstances he finds himself in than on his character. Something like this insight seems to underlie Sulak Sivaraksa’s critique of Buddhadāsa’s understanding of “Dhammic socialism” as a dictatorship with a benevolent dictator guided by rājadhamma (i.e., the virtues of a king).37 Sivaraksa considers this idea a weak point in Buddhadāsa’s thought “because dictators never possess dhamma”.38 A dictator could even abuse rājadhamma to justify their authoritarian and non-virtuous rule. The idea of a virtuous king (or dictator) as assumed by traditional Buddhist political theory, then, is dubious at best and probably even dangerously misleading.

Reckoning with conceptual change (2) — society

While the invention of the concept of the “state” was important, arguably, the development of the concept of “society” (as something separate from the state or the household of the king and the individuals within a society) constitutes an intellectual revolution. It is hard to overestimate the importance of the invention of “society” — without it, there would have been no social science, no social philosophy,39 and no political ideologies. And even more importantly, without it there can be no analysis of the social causes of social problems, and no critique of social problems in social terms.

This lack of a social perspective is further reinforced by another common aspect of ancient cultures: ahistoricism. In an overview of possible indicators separating “civilized” from “uncivilized” societies — in a descriptive rather than normative sense of the term “civilized” — Robert Bierstedt mentioned that uncivilized societies have “history but no historiography”.40 In other words, ancient and other premodern cultures have histories but no awareness thereof. More specifically, they lack an awareness of historical change and development. Instead, it is assumed that almost everything has stayed the same and will always stay the same. Numerous Buddhist sūtras and Jātaka tales assuming time-spans of many millions of years without any kind of sociopolitical, technological, or other kind of change are a case in point.

Ahistoricism and the lack of a concept of “society”, or the “social” as a sphere of life, together lead to system blindness, the inability to perceive social structures and systems and how they shape and are shaped by society and the people in it. Everything being the same color is effectively the same as there not being color at all. If all societies would be organized more or less the same and share the same sociopolitical and economic systems and structures, it would appear as if there would be no social structures and systems at all. Without a concept of the “social”, one cannot really think about society, and without an understanding that one’s society once was very different,41 one cannot really appreciate that different systems, structures, and institutions are possible.

Furthermore, without an understanding of social systems and what roles they play, one can only think of social processes and problems in individual terms, without realizing they are social processes or problems. Without systems, only individuals exist and only the thoughts and actions of individuals can have causal efficiency. And consequently, for pre-modern Buddhism, suffering is an individual problem with individual causes and an individual solution.

With the above in mind, let us return to the Four Noble Truths (4NT) and why those appear to be concerned with one kind of suffering only. Above I suggested two explanations. The first was that this appearance is mistaken. Life inherently involves suffering and 4NT offers a remedy for some future suffering (i.e., suffering in future lives) by preventing rebirth (or in other words, by preventing those future lives). The second was that 4NT focuses on the only kind of suffering that can be remedied. (I don’t think this second explanation is particularly plausible as an interpretation of 4NT, by the way. It seems pop-Stoicist more than Buddhist.) Notice that both of these explanations assume that worldly suffering is effectively unavoidable. The first does not address worldly suffering, but merely seeks to eventually escape it (by achieving nirvāṇa); the second sets worldly suffering aside to focus on a specific kind of mental/psychological suffering; but both assume that worldly suffering is an inherent part of life and that nothing can be done about that. It seems to me that this assumption is entirely due to system blindness and the lack of a concept of “society”. The causes of much (but not all!) worldly suffering are primarily sociopolitical and/or economic, but those aspects of life are invisible without a concept of “society” and without a grasp of the role and nature of sociopolitical and economic systems. This, of course, raises an obvious question: What does this mean for the analysis of suffering, its causes, and its remedies?

Recall that 4NT and related Buddhist thought are based on the premise that all suffering is bad (NT0), and that “all” here refers to the suffering of all sentient beings and to all kinds of suffering. According to the Buddha, suffering (of any kind) in future lives can be prevented by preventing rebirth (i.e., by preventing future lives). This is by no means easy, however. Rather, it requires many lives — and thus, much suffering — to eventually achieve nirvāṇa and avoid rebirth. Moreover, this only leads to the avoidance of that future suffering. But what about the suffering in this life? What about the suffering in those future lives before eventually achieving nirvāṇa? What about the suffering in the present and future lives of other sentient beings? Keep in mind that all suffering is bad, so (obviously) all this unavoided suffering is bad,42 and needs, therefore, to be prevented or alleviated as much as possible. To a considerable extent, Buddhism has always been committed to do exactly that (as explained above), although this may be more obvious (or more explicit) in the case of the Bodhisattva ethics of Mahāyāna Buddhism.

Nevertheless, this commitment is not based on or motivated by 4NT (which does not address any of this unavoided suffering in NT2 to 4), and no other systematic analysis of this unavoided suffering (similar to 4NT) is offered either. The reason for this is (probably, as argued above) something like system blindness and a lacking concept of “the social” leading to an implicit belief in the naturalness or inevitability of all this unavoided suffering and precluding any kind of analysis of its causes and alleviation. 20th century engaged Buddhists made a step forward in this respect, by more explicitly discussing “worldly suffering”, which is included in the kinds of unavoided suffering mentioned in the three questions in the previous paragraph, but their analysis remains stuck in a pre-modern conceptual framework. That is, the engaged Buddhists are as much affected by system blindness and a lacking category of “the social” and consequently, they blame individual defects like greed or selfishness, rather than the social (including political and economic) systems that are the underlying causes. Because of this, as James Mark Shields observed, “the current ideas of Buddhist economics are unable to imagine real alternatives to contemporary industrial capitalism”.43

If system blindness and the lack of a concept of “society” are removed, then the “zeroth” truth (i.e., the badness of suffering) and the Buddhist commitment to reducing, alleviating, and ideally, preventing all leads to different conclusions with regards to worldly suffering (in the sense intended here; i.e., involving the unavoided suffering mentioned in the three questions a few paragraphs back). Then, an application of the model of 4NT would blame much worldly suffering (but by no means all!) on the current dominant economic and political system: neoliberal capitalism. Then, a path towards the cessation of suffering would be political, if not revolutionary. Regardless of the details, if system blindness and the lack of a concept of “society” would be removed, Buddhism would be political, and a serious commitment to alleviate suffering would translate into political action. (As Yang Huinan suggested in the block quote in the introduction of this article. See also below.)

(Not) Reckoning with conceptual change (3) — literalism vs. “post-Buddhism”

A traditionalist Buddhist (or a Buddhist under the influence of neoliberal ideology) may balk at the ideas and conclusions suggested in the previous two sections and favor a kind of literalist fundamentalism instead. They might argue that the Buddha had no concept of “society” and, given that the Buddha was omniscient, this concept is, therefore, nonsense. And because the Buddha favored absolute monarchies with virtuous kings, that is the one and only form of government acceptable to Buddhism. Such a traditionalist (or neoliberal pseudo-traditionalist) might even argue that other ideas — even if they are clearly part of, or built upon, the Buddhist tradition — are un-Buddhist.

Arguably, if “Buddhism” is defined as “the thought and teachings of the Buddha”, then even most Buddhism would be post-Buddhist — that is, something that came after, and was built on “Buddhism”. This is obviously the case for Mahāyāna, but any serious scholar of Buddhism will tell you that Theravāda is not identical with the thought and teachings of the historical Buddha either. Hence, by this standard, Mahāyāna and Theravāda are post-Buddhist.44 Personally, I would find it absurd to draw the line between “Buddhism” and “Post-Buddhism” there. Surely, Theravāda and Mahāyāna are Buddhist. I’m also inclined to say that a Buddhism that seriously engages with social concepts and categories and that is cured from system blindness would still be Buddhism, but if a pre-modern conceptual framework is considered a defining category of Buddhism (and thus, Buddhism is forced, by definition, to be stuck in the Middle Ages), then much of what is argued in this article (and what is suggested by Yang Huinan and a few others) would be “post-Buddhist”. I’d be fine with that, as I don’t think that labels matter all that much, but I also think that drawing this boundary line between “Buddhism” and “Post-Buddhism” is equally absurd as drawing that line between the thought and teachings of the Buddha and everything that came after.

My opinion doesn’t matter much here, however, and I wouldn’t be surprised if many Asian sectarian Buddhists and Western Buddhists disagree, either because they prefer the safe secular marginalization of religion to the private sphere, or because they are blinded by neoliberal ideological blinkers, or for other reasons. I don’t care. If reactionary and neoliberal Buddhists prefer to deny Buddhism any sociopolitical role or relevance by sticking to something like fundamentalist literalism, then I’m happy to adopt the term “post-Buddhism” in reference to any “system” of thought that doesn’t insist on forcing Buddhist thought to remain stuck in pre-modernity.

The state as Bodhisattva

Yang Huinan’s (implicit) suggestion of the state as Bodhisattva (see the introduction of this article) may seem a radical innovation, but actually it is not. The idea that the king should be (or at least aspire to be) a Bodhisattva was very common in Buddhist political thought,45 and if we read “state” for “king” as suggested above and in “Buddhism and the State” (and which is also common in case of modern readings of pre-modern Western political thought),46 then the idea that the state should act like a Bodhisattva is quite commonplace — it is standard Buddhist political thought, and thus, anything but “radical”.

The implications of this idea are pretty radical, however, or at least they would be, if Buddhism is conceived as mostly apolitical (which it really never was). By far the most detailed specification of the moral obligations of a Bodhisattva can be found in Asaṅga’s Bodhisattvabhūmi, and under a modern reading of Buddhist political thought, all those obligations are obligations of the state, which effectively gives Buddhism a political program. (There are further sources for such a program, such as the rājadhamma, the Cakkavattisutta (DN26), and Nāgārjuna’s Ratnāvalī, but I’ll leave those aside here. My aim here is merely to illustrate the significance of a modern — rather than pre-modern or medieval — reading of Buddhist political thought; not to construct a or the Buddhist political program.)

Among the (many) duties of a Bodhisattva, the Bodhisattvabhūmi asserts that a bodhisattva:

takes care of those sentient beings who are ill, leads those who are blind and shows them to a road, causes the deaf to understand meanings with a [form of] sign language that represents words through symbols, and transports those whose limbs are deficient by carrying them [bodily] or by means of a vehicle.47

[…] protects sentient beings who are frightened from the objects that they fear.48

[…] dispels the sorrow of sentient beings who are in [various] states of distress.49

[…] furnishes the objects that are needed for subsistence to those who seek such objects[:] gives food to those who seek food; drinks to those who seek drinks; […]50

Additionally, the second of “the four acts that represent an extreme form of defeat” (i.e., the greatest moral transgression for a Bodhisattva) is:

the refusal to give material objects, because of a greedy nature and hardheartedness, to petitioners who have approached in a correct manner, who are suffering, miserable, and impoverished, and who lack a protector and someone to rely upon […]51

And listed among the “minor offenses” are failing to care for the sick, to assist those who are suffering,52 to dispel grief, to provide food to those who need it,53 and so forth.

It should be fairly obvious that these moral obligations of the state as Boddhisattva far exceed even the activities of a functioning welfare state. A closer analogy might be some kind of democratic socialism.

“Organicistic universal liberation”

Yang Huinan’s main point in the block quote in the introduction of this article is his advocacy of “organicistic universal liberation” instead of (or in addition to?) “mechanistic”, individualist “self-liberation”. He suggests that the latter is influenced by Confucianism (in a short subclause that I omitted above54), which seems unlikely to me.55 A more plausible explanation is that the individualism of “mechanistic self-liberation” is due to a lack of the concept of “society” and related concepts (as explained above). Lacking those, liberation can only be individual — that is, it is a liberation from individual problems, achieved by individual effort. However, as Yang points out, not everyone is able to “develop their conscience” and achieve liberation in this way, and moreover, “organicistic universal liberation” is more efficient because it “pays attention to the relations between sentient beings”.

What isn’t entirely clear, however, is what Yang means with “universal liberation”. The Chinese term he uses, 普渡 pǔ-dù (also written as 普度), is a traditional Buddhist concept referring to the kind of liberation (or saving) of all sentient beings as in the first of the four Bodhisattva vows. In other words, it refers to a Bodhisattva’s commitment to help all sentient beings to (eventually) achieve nirvāṇa and escape saṃsāra. Hence, it doesn’t usually refer to a liberation from what I called “unavoided suffering” above, that is, all the suffering (of all sentient beings) in this and future lives that isn’t avoided by (eventually) escaping saṃsāra. Importantly, what is commonly called “worldly suffering” is included in this “unavoided suffering”.

Yang either uses 普渡 pǔ-dù (universal liberation) to refer to liberation from suffering in the sense of achieving nirvāṇa and escaping saṃsāra (thus, ignoring unavoided suffering), or he uses the term in a more unorthodox sense to refer to a liberation from all suffering. (Or both?) The examples of “organicistic universal liberation” he gives are “wildlife laws and environmental protection laws, and even the establishment of a social welfare system”. If he uses the term 普渡 pǔ-dù in its traditional/orthodox sense, then this can only imply that he believes that enacting laws like these will improve the karma of all citizens (regardless of their involvement), thereby bringing them closer to escaping saṃsāra. This seems rather implausible, so the more likely (or more charitable, at least) interpretation is the second: he uses the term in an unorthodox sense. That is, “organicistic universal liberation” is alleviation of suffering of any kind. (Notice that — given these examples — Yang’s use of the term isn’t plausibly interpreted as a complete liberation from suffering either, which might make one wonder whether the English term “liberation” is an appropriate translation here.)

There is another reason to believe that this is the way Yang intended the term to be understood. As mentioned, he (implicitly) posits the state in the Bodhisattva role — that is, the state should be charged with the traditional Bodhisattva’s role of promoting universal liberation. If Yang intended 普渡 pǔ-dù (universal liberation) to refer to achieving nirvāṇa and escaping saṃsāra, then the state should be (primarily) occupied with helping people progress on the Buddhist path (i.e., the Eightfold Path, or the Tenfold Path, or the Bodhisattva perfections, or any other version of the path), but he doesn’t say anything like that, and moreover, it is hard to see how the state could do this (without breaking other Buddhist moral principles or guidelines, at least). If, on the other hand, “organicistic universal liberation” is alleviation of any kind of suffering, then the role and duties of the state are much clearer. (And much in line with the duties of a Bodhisattva mentioned in the previous section.)

Nevertheless, some of the things Yang says in the blockquote seem to be incongruous with this interpretation. For example, he suggests that “organicistic universal liberation […] liberates everyone together/collectively, or at least most people, all in one stroke”, which seems hyperbolic if we are talking about the state’s role in alleviating people’s (and other sentient beings’) suffering. Wildlife laws, environmental protection laws, and a social welfare system will not lead to the collective liberation from suffering of all people. Expecting otherwise would be absurd.

It seems, then, that Yang is sliding back and forth between the two interpretations of 普渡 pǔ-dù (universal liberation) mentioned. Some of the things he said in this interview only make sense if 普渡 pǔ-dù refers to the Bodhisattva’s commitment to helping all sentient beings achieve nirvāṇa and escape saṃsāra; other things only make sense if 普渡 pǔ-dù refers to a Bodhisattva’s duty to relief/alleviate/prevent suffering of any kind (explicitly including “worldly suffering”). However, it could be argued that these two duties or commitments are really the same, or more precisely, that the Bodhisattva’s duty to help sentient being escape saṃsāra is a special case of his duty to alleviate and prevent suffering in general.56 And this being the case, Yang’s apparent semantic flip-flopping might be less problematic than it appears at first glance.

Let’s return to the reasons why Yang advocates “organicistic universal liberation”. Those, again, are twofold: (1) not everyone is able to achieve liberation by themselves, and (2) the idea of individualistic/mechanistic self-liberation ignores the fact that we are social beings. The first of these points is another example of Yang’s apparent use of 普渡 pǔ-dù in a more orthodox sense. Specifically, he says that mechanistic self-liberation “does not necessarily enable everyone to develop their conscience”, which seems to have little to do with his use of 普渡 pǔ-dù as alleviation of suffering in general elsewhere. However, if “liberation” is to be understood in its traditional/orthodox sense here — that is, as (eventually) achieving nirvāṇa and escaping saṃsāra — then Yang’s first reason to reject “mechanistic self-liberation” fails, because his point that not everyone is able to achieve liberation by themselves is already recognized by traditional Buddhism in the form of the Buddhist division of religious labor: monks follow the path, working towards their liberation, while laymen improve their karma by supporting monks. (This division of religious labor is only acceptable, of course, if one accepts the underlying metaphysics involving a particular understanding of karma and rebirth, but that’s besides the point here.)

Yang’s first reason to reject “mechanistic self-liberation” only makes sense if we understand 普渡 pǔ-dù in the unorthodox sense as the alleviation and prevention of suffering of any kind, despite the fact that Yang’s words here strongly suggest a more orthodox interpretation of 普渡 pǔ-dù (within the context of this specific reason!). Now, if we interpret (1) as concerning universal liberation in the unorthodox sense, then Yang’s first reason to reject “mechanistic self-liberation” is just a recognition of the simple fact that many people are powerless individually to significantly alleviate their own suffering (of any kind) and that we collectively are much more capable of addressing the suffering of many people than they are themselves (individually). (Notice that, even though this is not literally what Yang said in this interview, it is much more in line with the overall argument he appears to be making.)

With regards to the second point, Yang says that “there is no liberation unless it is the liberation of all people in a country, or at least most of them, in one stroke”. Although I do not really understand why national boundaries matter here, I think that this is an important point. In the Bodhicaryāvatāra (chapter 8), Śāntideva argues that there is no fundamental difference between concern for my own future suffering and concern for the suffering of others because this future “me” is not numerically identical to menow either, or in other words, my future suffering is the suffering of some other. In a sense, Yang’s point that we are social beings and that it is, therefore, necessary to pay attention to the relations between social beings is the diametrical opposite of Śāntideva’s point, but these two important ideas are complementary rather than contradictory. Śāntideva’s argument that there is no fundamental difference between concern for what appears to be my future self and concern for some other other because I’m not even the same as mepast or mefuture disintegrates social reality57 into a collection of fleeting, atomic selves (or self-consciousnesses) that are all different from each other.58 Yang’s point brings these transient, atomic selves back together and re-integrates them by emphasizing the relations between sentient beings. Indeed, our transient selves (including our self-images, our personalities, our beliefs and desires, our values and perspectives, and so forth) are social products, formed and continuously reformed in social interactions with other transient selves for whom the exact same is the case. Those transient selves wouldn’t even exist without each other.

The fundamental point of both of Yang’s two reasons to advocate organicistic universal liberation instead of mechanistic self-liberation (regardless of whether Yang himself fully realized this) is a rejection of the liberal ideological dogma of the autonomous individual. Liberalism (from left-liberalism to neoliberalism or libertarianism and everything in between) is built upon the idea that we all are (and should be) autonomous, atomic individuals. Liberalism downplays or even overlooks the fact that our preferences, beliefs, and so forth are shaped and continuously reshaped in social interaction, and that our actions are influenced by, and influence others. Liberal autonomy presumes that each individual is uniquely responsible for their own actions and choices in past, present, and future, regardless of the extent to which those choice were influenced or even determined by social (and other) circumstances (that are fundamentally outside their control). Contrary to the this liberal dogma, we are not autonomous, however. How I think and speak, how and what I see and understand, what I want and dislike, and much more is all very heavily influenced by others and by social conventions, and likewise, I influence some of them. There are various relations of dependence, influence, and other kinds between me and others, and at a fundamental level, “I” wouldn’t even exist without interaction with others — that is, my sense of self, the languages I speak that allow me to think and express myself, and other key features of this transient “me” could only be formed in social processes. Humans are not “autonomous”; humans are deeply interdependent.

Most of us will never make much progress on (any version of) the Buddhist path (or even set foot on it), but this is almost entirely due to circumstances outside our control. Every one of us will encounter various kinds of suffering during their lifetimes, but very few of us will be able to significantly alleviate this suffering by themselves. Yang was entirely right when he pointed out that not everyone is able to achieve liberation from suffering (of any kind) by themselves (as “mechanistic self-liberation” presumes). We are interdependent, social beings (which was Yang’s second reason to reject “mechanistic self-liberation”, but which turns out to be closely related to the first). We need each other. We need to help each other. We can only effectively deal with suffering together.

If you found this article and/or other articles in this blog useful or valuable, please consider making a small financial contribution to support this blog, 𝐹=𝑚𝑎, and its author. You can find 𝐹=𝑚𝑎’s Patreon page here.

Notes

- Justin Ritzinger (2017), Anarchy in the Pure Land: Reinventing the Cult of Maitreya in Modern Chinese Buddhism (Oxford: Oxford University Press).

- 過去佛教曾被帝王以鬼神禍福作愚民的工具,今後則應該用為研究宇宙人生真相以指導世界人類向上發達而進步。— Taixu 太虛 (1940),〈我的佛教改進運動略史〉, in: Yinshun 印順 (ed.),《太虛大師全書》, Volume 19/29 (Taipei: Yinshun Culture and Education Foundation 印順文教基金會, 1988), p. 77.

- This interview was published in issue 1, but there was an issue 0 before that.

- The organicistic/mechanistic contrast probably refers to two opposing philosophical positions. Organicism compares the universe and its parts (including societies) to living organisms; mechanicism compares them to mechanisms or machines.

- …,一是「機械論式」的,開發每一衆生的良心以自淨其心,量上的都渡宗了,就叫普渡衆生。但問題是,這種…渡法,並不一定會使每一個人都會開發良心。所以必須要有另一層的普渡 —— 「有機論式」的普渡,注重衆生與衆生的關係,不渡則已,一渡即是全國人民或至少是大部分的人民,是爲衆體的渡。例如野生動物法、環保法之制訂,乃至社會福利制度的建立,都不是「自渡」,而是我所謂的「有機論的普渡」,因爲它們都是一渡就渡了許多人。人間佛教的信仰者,應該促請政府關心這些。 … 這種效率比較低,我們應該揚倡的是有機論式的普渡,有組織性、集體性,一渡就渡全體,或至少渡全體的大部分。 — Yang Jiaqing 楊家靑, Teng Jiaqi 滕嘉琦, and Lin Jiamei 林佳美 (1990), 〈建設人間淨土:座談會〉, 《佛教文化》 1: 10–16, at 15–16. (Thanks to Justin Ritzinger for checking and improving my translation of this passage.)

- James Deitrick (2003), “Engaged Buddhist Ethics: Mistaking the Boat for the Shore”, in: Christopher Queen, Charles Prebish, & Damien Keown (eds.), Action Dharma: New Studies in Engaged Buddhism (London: RoutledgeCurzon): 252–69, p. 263. Italics in original.

- Joanna Macy (1985), “In Indra’s Net: Sarvodaya & Our Mutual Efforts for Peace”, in: Fred Eppsteiner (ed.), The Path of Compassion: Writings on Socially Engaged Buddhism (Berkeley: Parallax): 170–81, p. 179.

- Śāntideva (8th ct/1995), The Bodhicaryāvatāra, Translated by Kate Crosby & Andrew Skilton (Oxford: Oxford University Press), §8.103.

- See also chapter 13 of: Lajos Brons (2022), A Buddha Land in This World: Philosophy, Utopia, and Radical Buddhism (Punctum).

- The Connected Discourses of the Buddha: A New Translation of the Samyutta Nikāya, translated by Bhikkhu Boddhi (Somerville: Wisdom, 2000), SN 56.11, p. 1844.

- See the quotation from Deitrick in the beginning of this section as an example.

- Hermann Yacobi (1881), “Ueber Sukha und Duḥkha”, Zeitschrift für vergleichende Sprachforschung auf dem Gebiete der Indogermanischen Sprachen 25.4: 438–40.

- Paul Younger (1969), “The Concept of Duḥkha and the Indian Religious Tradition”, Journal of the American Academy of Religion 37.2: 141–52.

- Younger, “The Concept of Duḥkha and the Indian Religious Tradition”, pp. 144–5.

- Stephen Jenkins (2003), “Do Bodhisattvas Relieve Poverty?”, in: Christopher Queen, Charles Prebish, & Damien Keown (eds.), Action Dharma: New Studies in Engaged Buddhism (London: RoutledgeCurzon): 38–49, at 39.

- It’s hard to say to what extent this was also the case in India, but according to Chinese sources, the standard curriculum at Nālandā (the biggest monastic university in the history of Buddhism that functioned from the fifth to twelfth century) included medicine, which suggests at least some concern with health care.

- Nichiren 日蓮 (1260), 『立正安國論』 [Establishing the Peace of the Country], T84n2688. Translation in: Philip Yampolsky (ed.) (1990), Selected Writings of Nichiren, Translated by Burton Watson and Others (New York: Columbia University Press), p. 14.

- The “threefold world” 三界 is the world we live in, the world of unawakened beings, including not just humans, but also animals, pretas, asuras, gods, and so forth. It is called “threefold” because of a traditional classification of the realms of these various beings into three kinds.

- Nichiren, 『立正安國論』. Translation: Yampolsky, p. 40.

- Ibid. p. 41.

- José Casanova (1994), Public Religions in the Modern World (Chicago: University of Chicago Press), p. 211.

- Punctum books, 2022.

- German for “saddle-time”; “saddle” in the sense of a pass in a mountain ridge.

- e.g., Reinhart Koselleck (1972), “Einleitung.” In Geschichtliche Grundbegriffe: Historisches Lexikon zur politisch-sozialen Sprache in Deutschland, Vol. 1: A–D, edited by Otto Brunner, Werner Conze, and Reinhart Koselleck (Klett Cotta): xiii–xxvii.

- The most influential text on the history of the concept of the “state” is: Quentin Skinner (1989), “The State.” In: Political Innovation and Conceptual Change, edited by Terence Ball, James Farr, and Russell Hanson (Cambridge University Press): 90–131. See also the entry “Staat und Souveränität”in Geschichtliche Grundbegriffe (edited by Otto Brunner, Werner Conze, and Reinhart Koselleck); and Alan Harding (1994), “The Origins of the Concept of the State”, History of Political Thought 15.1: 57–72.

- Skinner, “The State”, p. 101. Emphasis added.

- It would be interesting to know when and how exactly the concepts of the “state” and “society” were introduced into various East, South, and Southeast Asian languages, but I have not found much published work by conceptual historians detailing the history of these concepts in such languages. This is not very surprising, as conceptual history or Begriffsgeschichte is a relatively new and small research field, and as far as I know, very little work has been done on conceptual history in non-European languages. In case of Japanese, 社会 shakai, “society”, was coined in the late 19th century under Western influence [Yanabu Akira 柳父章 (1982), 『翻訳語成立事情』, (Iwanami Shoten)]. The modern Japanese word for state, 国家 kokka, is much older, but it only gained its modern meaning relatively recently, again under Western influence. China, in turn, imported many modern/Western concepts from Japan. I expect something similar to be true for South and Southeast Asian languages.

- The main sources describing the conceptual history of “society” in German and English are the entries “Gesellschaft, bürgerliche” and “Gesellschaft, Gemeinschaft” in Geschichtliche Grundbegriffe; Johan Heilbron, Lars Magnusson, and Björn Wittrock, eds. (1998), The Rise of the Social Sciences and the Formation of Modernity: Conceptual Change in Context, 1750–1850 (Kluwer); and Peter Wagner (2001), A History and Theory of the Social Sciences: Not All that is Solid Melts into Air (Sage).

- “Die Gesellschaft besteht nicht aus Individuen, sondern drückt die Summe der Beziehungen, Verhältnisse aus, worin diese Individuen zueinander stehn.” (Karl Marx, Grundrisse der Kritik der politischen Ökonomie, MEW 42: 189.)

- Hence, this “watershed” is not exactly a narrow ridge; it is more like a vague transition zone.

- Vol. 31, pp. 501-521.

- Lajos Brons (2024), “Buddhism and the State: Rājadhamma after the Sattelzeit”, Journal of Buddhist Ethics 31: 501-521.

- Absolute monarchies like Saudi Arabia, Liechtenstein, and North Korea come close, but even in those the power of the ruler is limited in a number of ways and citizens are not the ruler’s personal property (even if they are unfree).

- Matthew J. Moore (2016), Buddhism and Political Theory (Oxford University Press).

- Moore, Buddhism and Political Theory, p. 124.

- See: Brons, “Buddhism and the State”.

- Buddhadāsa (1986), Dhammic Socialism (Thai Inter-religious Commission for Development).

- Quoted in: Tavivat Puntarigvivat (2013), Thai Buddhist Social Theory (World Buddhist University).

- There would be and was political philosophy (as the branch of philosophy that is concerned with the legitimacy and organization of the king or state), but there could be no philosophical inquiry into questions about the good society. Most of the core concerns of social philosophy – justice, equality, liberty, distribution of wealth and power, and so forth – depend on the concept of the “social” as a sphere of life.

- Robert Bierstedt (1965), “Indices of Civilization”, The American Journal of Sociology 71.5: 483–90, p. 490.

- Or a neighboring society is relevantly different.

- It is unavoided suffering in the sense that it is not avoided by (eventually) achieving nirvāṇa (after many rebirths).

- James Mark Shields (2018), “Buddhist Economics: Problems and Possibilities”, in: Daniel Cozort and James Mark Shields (eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Buddhist Ethics (Oxford: Oxford University Press): 407–31, p425. (Emphasis in original.)

- And the same would be true for reconstructionist “early Buddhism”, as such reconstructions are always heavily influenced by ideas that are hegemonic at the time (and in the intellectual environment) of the people doing the reconstruction.

- The most prominent example might be Nāgārjuna’s Ratnāvalī. See also Moore, Buddhism and Political Theory.

- Brons, “Buddhism and the State: Rājadhamma after the Sattelzeit”.

- Asaṅga (4–5th ct/2016), The Bodhisattva Path to Unsurpassed Enlightenment: A Complete Translation of the Bodhisattvabhūmi, Translated by Artemus Engle (Boulder: Snow Lion), p. 250.

- Ibid., p. 252.

- Ibid., p. 253.

- Ibid.

- Ibid., p. 267.

- Ibid., p. 294.

- Ibid., p. 296.

- 但問題是,這種博統受到儒家思想影響的渡法,並不一定會使每一個人都會開發良心。— I underlined the passage that I omitted above.

- There is a lot of Confucian influence on East-Asian Buddhism, of course — it would be absurd to deny that. What I find unlikely is that this individualism specifically can be traced back to Confucian influence, although it is possible that Confucian influence strengthened or reinforced it.

- It is not merely a special case, of course, as escaping saṃsāra is the only liberation from all further suffering according to Buddhism.

- In a broad sense of “social” including all sentient beings.

- Notice that Buddhism rejects the self as some kind of persistent, defining essence. It doesn’t reject the notion of transient self-consciousnesses that matters here.