Some people seem to believe that it is too late to fight climate change. Others seem to believe that this kind of fatalism is as dangerous as climate change denialism (because both effectively advocate not doing anything).1 It’s hardly a secret that I’m rather pessimistic about climate change and its effects – just have a look at what I’ve written about the topic before – but that doesn’t mean that I think that it is “too late” to fight climate change. Rather, I think that the notion of it being “too late” (or not) in this context is nonsensical. The purpose of this short article is explaining why this is the case.

The claim that it is “too late” is meaningless without a statement of what it is too late for. So, let’s start with considering a few of the options.

Is it too late to avoid climate change? Yes, and it has been for many decades, perhaps even half a century.

Is it too late to avoid catastrophic climate change? It depends on what you mean with “catastrophic”. If we stop emitting CO₂ within a decade, we can probably limit average global warming to approximately 1.5°C (or maybe 2°C). That would be bad, and it would even be catastrophic on regional scales, but probably not on a global scale.2 Hence, technically, it is not too late to avoid catastrophic climate change (in that sense), but this is not a real possibility. We cannot reduce our emissions that much that fast.3 So, perhaps a more accurate (or more honest, at least) answer to the question is: Yes, it is too late to avoid catastrophic climate change.

Is it too late to stop climate change? Strictly speaking, No. If we stop emitting CO₂ the global climate will eventually stabilize. How long that will take depends on how much CO₂ we emit before stopping, what kind of feedback effects are triggered, and what kind of tipping points we pass on the way. Melting of ice caps in the polar regions until a new stable state is reached (which may be when all ice has melted, but which probably is reached sooner than that, especially in case of Antarctica) will take many centuries or even millennia, for example. And soil formation and the evolution of new ecosystems – which influence evapotranspiration and thereby (regional) cloud cover, wind, temperature, and precipitation – take place on similar time scales. Of course, the sooner we stop emitting CO₂, the sooner the Earth system will adapt, but in any case, eventually a new more or less stable situation will be reached, until and/or unless that new stability is disrupted by some external event. However, given how much we have already emitted and will almost certainly emit in the next decades, and taking human time scales in consideration (i.e. decades rather than centuries or millennia), a more appropriate answer to the question is: Yes, the global climate will continue changing for the rest of our lives (although it is possible that after the first decade after CO₂ emissions cease further changes will be relatively subtle and gradual).4

Is it too late to avoid the end of civilization as we know it? Before answering that question, I must emphasize that there are essentially two options (with many minor variants of both): either we adapt quickly and avoid an escalation of climate change to apocalyptic proportions, or we don’t. Obviously, in the second scenario civilization as we know it would end. Instead, we’d get massive famines, (civil) war, global societal collapse, and other disasters. However, as I explained in The Lesser Dystopia, the first scenario would require such drastic changes to the ways we live and work, to the ways we consume, produce, and distribute goods, and to the ways societies and governments are organized and function that what we would end up with would be a civilization, but not civilization as we know it. Hence, the answer to the question is: Yes, if we want to avoid a global disaster we have to end civilization as we know it (and replace it with something less harmful), because if we don’t, then global disaster will end civilization in a much more apocalyptic fashion.

Is it (therefore) too late to fight climate change? No, it’s never too late. Climate change is not like a switch with two positions. This is the problem with the notion of it being “too late”: it promotes black-and-white thinking. Either it is too late or it isn’t – black or white. Either we’ll have global catastrophe or everything will be fine. Climate change doesn’t work like that. We have already moved beyond the “everything will be fine” option – that’s no longer an option – but there are gradations of catastrophe. We have a choice (at least in theory!) between different levels of disaster. We can choose (again, in theory) how bad we’ll let things get. (Whether we have that choice in practice depends very much on the distribution of political power. As long as we are powerless, we have no choice in practice, of course, but that problem is outside the scope of the present article.5)

If there is a single number that determines the fate of human civilization and even humanity itself (and/or other animal species), it is the number of people (and/or other kinds of animals) Earth can feed. A couple of decades ago, some scientists believed that more CO₂ would make plants grow bigger and faster, but unfortunately it turns out that it doesn’t make them any more nutritious, so that supposed positive effect of CO₂ evaporated. All other effects of climate change – heat, drought, extreme weather, and so forth – are negative. The warmer it gets, the less cultivatable land there will be available, and thus the less people can be fed. Fast (global or regional!) changes in this respect lead to (global or regional) famines, food riots, refugee flows, and possibly (or eventually) even civil war and societal collapse. Only if changes are very slow will peaceful adaptation be possible, and even then this will require significant coordination and cooperation.

The most important question, then, is how many people Earth can feed at different levels of warming. Unfortunately, there is no clear answer to that question – we don’t even know how many people Earth could sustainably feed at the temperature level before global warming started to have a significant impact (i.e. 1°C or more below the present temperature). Futurists, of course, tend to claim that Earth could feed tens or even hundreds of billions of people, but that would depend on technologies that either aren’t scale-able or aren’t even available yet, and/or completely ignores resource limitations (or other limitations). And obviously, Earth can feed 7.8 billion people because it is doing so now, but the question is how many people can be sustainably fed, and it should be fairly obvious that the current situation is far from sustainable.

In 2004, Jeroen van den Bergh and Piet Rietveld published a meta-analysis on this topic and that is, as far as I know, still the best source available.6 Taking various limiting factors into account, their estimates of a sustainable population limit range from 0.7 billion to more than 100 billion, depending on which factors exactly are taken into account and how. This is, of course, a huge uncertainty range, but the higher estimates assume universal access to the best technologies (and necessary resources), and are thus better regarded as science fiction than as real possibilities.7 Van den Bergh and Rietveld argue that “efficient use of data suggests that the median of all method-oriented (objective) studies is a good estimate”, which “leads to a limit of 7.7 billion people”.8

In The Lesser Dystopia, taking necessary changes in agriculture and the food industry into account (as well as unavoidable short-term effects of climate change), I estimate a global population limit between 2.5 and 3 billion. That is, of course, significantly lower than Van den Bergh and Rietveld’s estimate, but their estimate is for a “cool” Earth (i.e. before warming) and doesn’t take into account that we probably also have to stop using artificial fertilizers, for example. In Stages of the Anthropocene, I estimated that if we heat up the planet by 10°C only about 100 million people could survive, but I’m now inclined to say that even that number might be optimistic. (I also don’t believe anymore that we’ll be able to heat up the planet that much.) On the other hand, taking feedback effects and tipping points into account, 6°C does not seem unlikely unfortunately (although there still is a good chance that we’ll stay below that) and the number of people Earth can feed at that level of warming will probably not be very much higher. Maybe 1 billion at most, but probably significantly less.

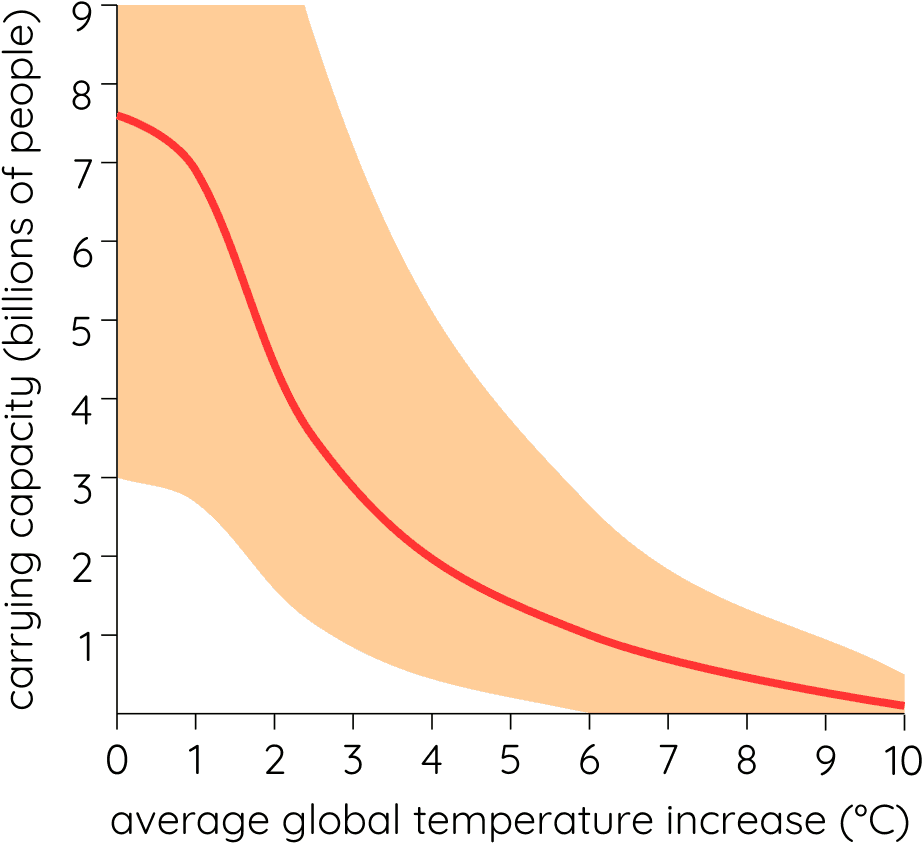

These are all rough estimates, of course, and there are big uncertainty margins, but in the present context that doesn’t really matter.9 What matters here is that there is a curve that relates global carrying capacity to temperature increase – even if we don’t know what that curve exactly looks like – and what matters is that this curve is continuously decreasing. Roughly, it looks something like this:

The red line in this graph is the hypothetical best expectation (starting at Van den Bergh and Rietveld’s 7.7 billion) and the light orange zone the uncertainty range (ignoring extreme and outlandish scenarios). Perhaps, this graph is a bit too pessimistic – that is, the slope might be (slightly) less steep – or perhaps, it is too optimistic – the starting point may be much closer to the lower edge of the uncertainty range depicted, for example. Neither of that really matters, however. What matters is that we can reasonably say that (if we ignore science fiction scenarios) the curve relating the number of people Earth can sustainably feed and average global temperature increase looks something like this, and that the actual curve is almost certainly entirely within the uncertainty range depicted. And that fact alone should be enough to show why it is never too late to fight climate change. 4°C will be worse than 3.5°C, which will be worse than 3°C, and so forth. Every degree – no, every tenth of a degree – matters.

The red line in this graph is the hypothetical best expectation (starting at Van den Bergh and Rietveld’s 7.7 billion) and the light orange zone the uncertainty range (ignoring extreme and outlandish scenarios). Perhaps, this graph is a bit too pessimistic – that is, the slope might be (slightly) less steep – or perhaps, it is too optimistic – the starting point may be much closer to the lower edge of the uncertainty range depicted, for example. Neither of that really matters, however. What matters is that we can reasonably say that (if we ignore science fiction scenarios) the curve relating the number of people Earth can sustainably feed and average global temperature increase looks something like this, and that the actual curve is almost certainly entirely within the uncertainty range depicted. And that fact alone should be enough to show why it is never too late to fight climate change. 4°C will be worse than 3.5°C, which will be worse than 3°C, and so forth. Every degree – no, every tenth of a degree – matters.

Indeed, it is too late to stop climate change, or even to avoid catastrophe, but it is never too late to make a choice between bad and even worse outcomes. The planet we leave to our children and their children will be nothing like ours. In many respects, it will be hellish. But in the same way that Dante’s hell has different circles, each worse than the next, the climate hell we leave for our children has different levels of hellishness. We have the moral duty to make it as tolerable – that is, as “un-hellish” – as possible. And for that reason, we can never give up. It is never too late to fight climate change.10

If you found this article and/or other articles in this blog useful or valuable, please consider making a small financial contribution to support this blog, 𝐹=𝑚𝑎, and its author. You can find 𝐹=𝑚𝑎’s Patreon page here.

Notes

- Michael Mann is probably the best known enemy of climate change fatalism.

- Actually, I’m not so sure about this. 2°C may already be enough to trigger a cascade of societal collapse. See: A Theory of Disaster-Driven Societal Collapse and How to Prevent It.

- See also: Carbon-neutrality by 2050.

- The direct warming effect of CO₂ emissions – and that is likely to be the biggest factor, except in case we trigger massive permafrost melting – is expected to reach its peak roughly ten years after emissions stop. See, for example: Andrew MacDougall et al. (2020), “Is there Warming in the Pipeline? A Multi-model Analysis of the Zero Emissions Commitment from CO2”, Biogeosciences 17: 2987-3016.

- On this topic, see Enemies of Our Children.

- Jeroen van den Bergh & Piet Rietveld (2004), “Reconsidering the Limits to World Population: Meta-analysis and Meta-prediction”, BioScience 54.3: 195-204.

- The authors call those scenarios “somewhat unrealistic or at best futuristic”. (p. 202)

- p. 202.

- It does matter, on the other hand, for my “project” of coming up with better predictions. (See the blog post with that title.) So for that project I need to find better predictions and other relevant data.

- Even in the extreme (and unlikely) scenario of human extinction, it can easily be argued that we have the moral duty to leave the planet as inhabitable as possible to other animal species.