(This is part 5 in the No Time for Utopia series.)

Let’s say that you want to avoid the Mad-Maxian hell of societal collapse that climate change is making increasing likely, then how can and should you try to do that? You’d have an incredibly powerful and well-connected enemy, and just asking them to give up their short-term profits in order to save the planet isn’t likely to have any effect – at least, it hasn’t had any effect thus far. Then what?

Very many different answers can be given to that last question, but I want to focus here on the most radical answer: war – or insurgency, technically, as it would be a fight between non-state parties and state parties. You might wonder why I want to discuss the most extreme means to establish the goal – avoiding global societal collapse – if other means available, but I have several reasons for this approach.

Firstly, it is by no means certain that there indeed are other means available, but more importantly, even if there are, focusing on the most extreme means may help clarify options, limits, tactical aims, and so forth that might remain hidden (or insufficiently exposed, at least) when focusing on less extreme means.

Secondly, there is a relatively uncontroversial theory in the ethics of war that can help answering the question about whether and how to fight a climate insurgency, while there is no unifying theoretical framework that is similarly helpful in answering questions about other means and tactics. This “relatively uncontroversial theory” is Just War Theory. (If it wasn’t obvious yet from the title of this article, I’m concerned here with the morality and justification of climate insurgency, and not so much with the effectiveness of tactics and strategies. The questions I aim to answer are whether and when climate insurgency is right. Just War Theory answers similar questions with regards to war.)

Thirdly, we’re already at war. This may be less obvious if you’re living in a Western country, although in some of those peaceful protesters and climate activists are also increasingly treated as terrorists, attacked by soldiers and militarized police, teargassed and pepper-sprayed, and even imprisoned. But outside the West climate activists – people defending their land and water – are being killed. It’s hard to find reliable statistics, but Shell and other oil companies are responsible for 100s (if not 1000s) of deaths in the Niger delta (Nigeria), for example. (There is a very incomplete list of murdered environmental activists at Wikipedia.1)

In any case, if we go to war, we won’t be the ones who started it. They started the war when they decided to obstruct action to prevent climate disaster in the 1990s. When they started their campaign of lies and deception.2 When they changed an issue that should concern us all into a political issue.3 They started the war when they destroyed landscapes and livelihoods. When they polluted air and water. They started the war when they send the army or police to attack or even kill people who were defending their land and water. They started the war. Perhaps, it is time to start fighting back.

But there are many ways to fight, and even if the enemy is using violence to ensure a profitable destruction of our planet, that doesn’t necessarily mean that we have the right to use violence to prevent that.

The goal and the enemy

Before laying out Just War Theory and its application to a hypothetical climate change insurgency, we need some clarity on both the goals and the enemy (or enemies) of the insurgents. The goal would be to prevent or minimize catastrophic climate change. To what extent catastrophe can still be prevented is debatable, but it can certainly still be minimized, and every degree of lesser warming matters. This would require a very fast decrease in the use of fossil fuels as an energy source, and given that most of our energy comes from fossil fuels and that much of the world economy as well as most food production is entirely dependent on energy, the implications of a decrease in fossil fuel use cannot be overestimated. We cannot feed the current world population without fossil fuels, and thus we need a population reduction, which can be achieved either by means of war and starvation or by birth control. I’m assuming that every sane person will agree with me that the second is preferable.

Furthermore, capitalism requires economic growth and economic growth requires fossil fuels (and is, moreover, the root of the current climate catastrophe), so capitalism will have to be replaced as well. I don’t know what exactly should replace it, but it might have to be some kind of repressive state to ensure fossil fuel reduction and population control, and to implement various other measures that will be necessary to avoid or minimize massive suffering due to climate disaster, economic collapse, and other crises. And that state cannot be funded through taxation of the poor (which by then will include much of the former middle class) – it will require expropriation of the ill-gotten wealth of the rich (who are largely to blame for the climate crisis anyway).4

Hence, much in line with the rejection of ideal theory that framed this series, the goal of this hypothetical insurgency is not an Utopian goal. Rather, it is the Lesser Dystopia. The choice is between this Lesser Dystopia and barbarism. The alternative (i.e. the Greater Dystopia) is a hotter world in which billions will die of starvation and war, a world in which the rich will be safe for a while in their air-conditioned fortresses, but in which ultimately everything will give way to continuous disasters in conditions that make the Mad Max movie series look like a fairy-tale.

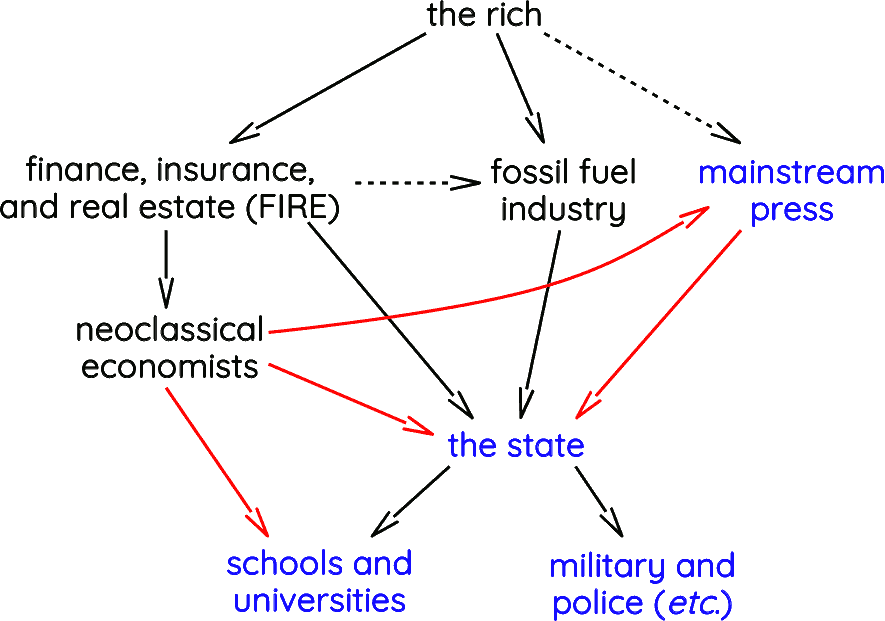

The previous paragraph summarizes some of the main points of The Lesser Dystopia, the third chapter in this series, which discussed what is necessary to avoid the scenario of global societal collapse that was sketched in the second chapter, On the Fragility of Civilization. The previous (fourth) chapter, Enemies of Our Children presented a rough sketch of the enemy in a hypothetical climate insurgency. That enemy is manifold, pervasive, and extremely powerful. It consists of all groups and institutions that aim to prevent the status quo at all costs, and thus to prevent the prevention of climate catastrophe. The metaphorical “spider” in the web of money, power, and death that forms the enemy is the global financial and industrial elite – the rich, and particularly, the super-rich. They are most to blame for climate change,5 and have profited from it most. They have most to lose from preventing climate catastrophe and are threatened the least by the short-term effects of climate catastrophe (thanks to their air-conditioned fortresses and other safeties and insurances that their money can buy). The rich control the financial (FIRE) sector, the fossil fuel industry, and most of the mainstream press, and through those they control public opinion and the state. This web of control is illustrated in the following figure:

(For an explanation of the use of color in this figure, as well as for a more extensive description of the enemy, see Enemies of Our Children.)

Just War Theory

Above I wrote that the fact that our enemy is using violence to ensure profitable environmental destruction doesn’t imply a right to use violence to prevent that. Hence, the main question to be answered in this article concerns the question whether political violence is or can be a morally acceptable means to try to prevent climate catastrophe.

The use of potentially deadly violence as a means within a larger struggle against a relatively clearly defined enemy and with a political goal more or less defines insurgency (or terrorism – the difference between the two will be explained below), and insurgency is a kind of war. There is a widely accepted framework in the ethics of war, Just War Theory (JWT), even though there is a lot of debate about various aspects and details thereof.6 JWT is a particularly useful framework in the context of this series, because it recently experienced a turn away from ideal theory – that is, it increasingly bases its arguments on actual conflicts rather than artificial abstractions – and the rejection of ideal theory is a key methodological principle of this series.

Traditionally, Just War Theory (JWT) was about wars between states, but such wars have become increasingly uncommon. Civil wars and insurgencies have become the typical kinds of wars, and therefore, a turn away from ideal theory should be a turn towards the ethics of civil war and (counter-) insurgency. Unfortunately, most work in JWT still focuses on traditional wars, but a few philosophers have written about the application of JWT to civil wars and insurgencies. The most important contribution to that (still small) literature is Jonathan Parry’s “Civil War and Revolution”.7 I’ll very briefly summarize JWT here,8 and discuss its application to a hypothetical climate insurgency in the following two sections.

Traditional JWT consists of two parts, Jus ad Bellum and Jus in Bello. The former is about the moral justifiability of a particular war; the second is about the moral justifiability of particular acts within a war. Since the present topic isn’t morality in (traditional) war (bello in Latin), but morality in insurgency (seditio), we should, perhaps, talk of Jus ad Seditionem and Jus in Seditione instead,9 and I’ll use those two Latin terms as section titles below.

Both Jus ad Bellum and Jus in Bello are typically conceived as lists of principles. Jus ad Bellum (or Jus ad Seditionem) includes six principles:

1. Just cause – the war is fought for the right reason(s);

2. Competent authority – the war is fought by something that is entitled to fight wars;

3. Right intention – the war is fought for a just goal (and is intended to have a just outcome);

4. Reasonable prospects of success;

5. Proportionality – the moral benefits achieved by the war (if successful) outweigh the moral harms of the war itself; and

6. Necessity – the war is a last resort (i.e. there is no other, less harmful way to achieve a sufficiently similar result).

Jus in Bello (or Jus in Seditione), typically includes only three principles:

1. Noncombatant immunity (or Discrimination) – the principle that only combatants (and/or other responsible parties) may be targeted;

2. Proportionality – the moral (and tactical) benefits achieved by some act (in war) (if successful) outweigh the moral (and other) harms of that act itself;

3. Necessity – violence is always a last resort (i.e. there is no other, less harmful way to achieve a sufficiently similar result).

The following two sections discuss the application of these principles to a hypothetical climate insurgency. Because some of the aspects of Jus ad Seditionem (i.e. the justification of insurgency) depend – in a sense – on aspects of Jus in Seditione (i.e. the justification of particular acts and tactics within an insurgency), I’ll start with the latter. In other words, I’ll postpone the question whether climate insurgency is justified at all and will focus on what kinds of tactics would be allowed within such a insurgency first.

Jus in Seditione

For now, we’ll assume that climate insurgency is justified (whether it actually is or can be will be discussed below). The question, then, is What kind of acts or tactics are the insurgents allowed to use? What is the right way to fight?

Three criteria were introduced above: Noncombatant immunity (or Discrimination), Proportionality, and Necessity. All three restrict the moral acceptability of the use of violence, but in different ways. The first focuses on the targets of violent acts, while the second and third compare the violent act under consideration with non-violent alternatives including non-action. If less harmful means are available to achieve a similar result, then violence is not an acceptable means. And if the tactical or strategic benefits that are expected to result from some violent act are relatively minor, then violence is not an acceptable means either. Or in other words, violence is always a last resort and the expected benefits from the act of violence must outweigh the harm of the act itself. It should be fairly obvious that these two principles imply that there cannot be a general rule that dictates what kinds of violent acts are allowed and what kinds are not – it depends on context, alternatives, goals, and so forth. And consequently, whether violent acts pass these criteria has to be judged case by case.

Discrimination

Nevertheless, the restrictions posed by Proportionality and Necessity are severe, but the first may be an even bigger obstacle. The Principle of Discrimination (or Noncombatant immunity) forbids any kind of violence targeted at “noncombatants”, but that raises a question what and who these “noncombatants” are. A simplistic answer would be that anyone who is not a combatant is a noncombatant, and that combatants consist of the armed forces of the states involved (i.e. army and police), but that answer is overly simplistic, as police officers and soldiers who are not involved in fighting a hypothetical climate insurgency and/or other kinds of climate action are not parties in that fight. Or in other words, they are noncombattants in the climate insurgency, and are thus not acceptable targets. But then, who are?

Arguments for the acceptability of targeted deadly violence in war (or insurgency) typically focus on the “right to life”. Michael Walzer, the father of modern JWT, proposed that some people, by posing a lethal threat to others, can lose their right to life, but this idea has been criticized in a variety of ways. Pacifists argue that no one can ever lose their right to life and there is much to say for that point of view. However, there may be situations in which lives on both sides are at steak, such as situations in which a few enemies threaten the lives of many innocents or allies. Perhaps, those enemies don’t lose their right to life in that situation, but surely neither do the innocents and allies. Of course, in such a situation violence would be used in collective self-defense, but arguable, that’s the whole point of a climate insurgency: collective self-defense against the threat posed by climate Armageddon.

Posing a threat is, moreover, not the only criterion mentioned in the literature that may lead to someone losing their right to life. An alternative is responsibility or liability. Those most liable for the war (on the enemy’s side) then are least protected by the Principle of Discrimination. This, of course, puts political leaders and others who are effectively in control in the spotlight. It also leads to a radically different answer to the question of those who could be targeted. Threat-based views appear to focus on the enemy “soldier” in the street, at the bottom of the line of command, while liability-based views aim for the top. Such responsibility/liability-based views are controversial, however.

The question of who can be justifiably targeted by violent action in war is probably the most hotly debated topic within JWT – it certainly is the most controversial. What is uncontroversial, however, is that is almost never acceptable to intentionally kill civilians (i.e. non-soldiers). An important distinction that supports this judgment is that between opportunistic and eliminative violence. Eliminative violence serves a direct tactical (or strategic) goal: it removes a threat that could not reasonably be expected to be removed in any other way. Opportunistic violence does not remove a threat, however, but is an attempt to use fear and suffering towards other, indirect goals.

Opportunistic violence is the hallmark of terrorism. The terms “terrorism” and “terrorist” are, of course, often abused to denounce any kind of political violence in support of a goal one disagrees with. (Hence, the difference between a “freedom fighter” and a “terrorist” is often merely one of support or lack thereof for his/her political goals.) But that is a kind of politically motivated ignorance. The term “terrorism” derives from “terror” and refers to the use of terror or fear (created by means of violence) as a tool to try to bring about some political goal. In other words, terrorism is defined by opportunistic violence.

There is near universal agreement that opportunistic violence is not acceptable. This might seem too strong, however. Surely, if opportunistic violence could have prevented the Holocaust, it would be justified, wouldn’t it? I’m inclined to say that it would, but at the same time, I cannot imagine how opportunistic violence could have prevented the Holocaust. Or how it could prevent the climate holocaust. Historical examples of effective opportunistic violence are sieges and aerial bombing campaigns against civilians to force an enemy state to surrender, and the use of terrorist attacks by ISIS (and related extremists) as a recruiting tool,10 but I can’t see anything analogous to those that might have prevented or stopped the Holocaust (or that might prevent catastrophic climate change). So, even if opportunistic might – in principle – sometimes be morally acceptable in very particular and very extreme cases, this would depend on whether it can reasonably expected to achieve its goal and that is exceedingly unlikely in a climate insurgency.

Conclusion

Two things should be noted about the foregoing. Firstly, the Principle of Discrimination (or Noncombatant immunity) does not apply to material targets. Whether it is morally acceptable to blow up a coal plant, investment bank, or TV station without human (and animal?) casualties (if that is possible) is outside the scope of this principle, and thus entirely guided by the other two principles.

Secondly, to a large extent all three principles can be reduced to the Principle of Proportionality: expected benefits must outweigh expected harms. What the preceding discussion points out is that some harms weigh heavier than others: killing a civilian is much greater harm than killing a “combatant”, for example. But that discussion also made clear (I hope) that it is far from clear what or who the enemy combatants are, which puts a very severe restriction on the use of potentially deadly violence against human targets.

Perhaps, this should be taken to imply that even if a climate insurgency is morally justified, intentionally killing people within that insurgency is almost never acceptable. If violence is allowed, it would be violence against things rather than people.11 In any case, any act of violence under consideration must be judged by its proportionality and necessity. If other means are available, and if expected benefits do not outweigh expected harms, then violent means are not acceptable.

Satisfying those criteria – if one would want to – might be a challenge, moreover. I’m not sure whether blowing up a coal plant could reasonably be expected to be tactically worthwhile, for example. On the other hand, burning down the offices of Fox News may very well pass these criteria.

So in conclusion (of this section), it is probably fair to say that even if climate insurgency is morally justified, there may not be very many justifiable violent acts within it. Again, much depends on context, goals, and alternatives, so a categorical ban on violence is too strong, but the limitations are so forceful that the question of the justifiability of the insurgency itself almost becomes moot.

Jus ad Seditionem

Whether a climate insurgency is justified is determined by the six criteria mentioned above: Just cause, Competent authority, Right intention, Reasonable prospects of success, Proportionality, and Necessity. The last two are analogous to the principles of the same name in Jus in Seditione but applied to the insurgency as a whole. By implication, they are closely related to the fourth principle, Reasonable prospects of success, and therefore, I will discuss those three principles together, but only after looking into the first three.

Just cause and right intention

Traditionally, the only just causes for war (or insurgency) are self-defense or avoiding some other harm that is so great that it outweighs the harm of the war itself. A climate insurgency seems to easily pass this criterion: it is self-defense of the young and the poor and defense of future generations against the imminent and immense harm of catastrophic climate change. Climate insurgency also passes the criteria of right intention if what it aims to establish (i.e. something like the “Lesser Dystopia”) is a better and more fair outcome than any other (realistically available) alternative. Of course, this is still open for debate, but given all we know now, the Lesser Dystopia may be the best possible future indeed, and therefore, an insurgency aiming to establish that certainly has a “right intention”.

Competent authority

Traditionally, only states were considered to have the authority to start a war, but this view is now generally considered overly “statist” and two competing views have replaced it. One aims to replace the traditional view with one that grounds authority in something like consent; the other argues that the authority requirement should be abolished altogether. The main argument for the abolitionist view is that the consent view faces several serious problems. Jonathan Parry reviews the main problems,12 but I want to add one more.

According to the consent view, a group of would-be insurgents has the authority to start an insurgency if they have popular support in the form of some kind of (qualified) majority consent from the people on whose behalf they want to start an insurgency. Now, imagine that due to successful propaganda or brainwashing a substantial majority of Jews during WW2 believed that they were rounded up for free luxury vacations in a tropical paradise, and that because of this they did not consent to any attempt to block or hinder the Holocaust. Then, lacking consent, an anti-Holocaust insurgency would lack competent authority, and would, therefore, not be morally justified (on that ground), but that conclusion seems absurd – it would imply that effective propaganda makes all resistance immoral.

A possible solution to this problem is that hypothetical or counterfactual consent is sufficient: a group of insurgents has competent authority if it can be reasonably expected that rational, well-informed, and non-brainwashed members of the group on whose behalf the insurgency is (to be) fought would consent with that insurgency. A possible alternative solution (in at least some cases) can be found in Parry’s solution for another problem for the consent view – namely that requiring majority consent can have unacceptable implications:

When a just cause for war is based purely on individual rights (such as a war of defence against mass murder or enslavement), each individual right-holder has the moral power to authorise a third-party to defend their rights, which is unaffected by the refusal of other victims. By contrast, if the just cause is grounded in the defence of interests that are protected by collective rights, that right can only be permissibly acted upon by those who have been collectively authorised to do so.13

If the insurgency in question is fought to prevent a serious individual rights infringement and at least one member of the group whose rights are infringed consents, then the insurgents have competent authority. Hence, provided that the just cause is of the right kind, only one non-brainwashed supporter is sufficient.

The brainwashing/propaganda scenario is important here because due to hegemony (the social processes by means of which the values and beliefs that serve the interests of the ruling class become the common sense values and beliefs of everyone)14 a significant part of the people who are threatened by climate change may not realize and/or understand the nature and extent of that threat. Many – perhaps even most – people are effectively “brainwashed” (although this is not “brainwashing” in a strict sense of that term, of course). Given what is at stake, if the other requirements for a just insurgency are met, it can be reasonably expected that a rational, well-informed, non-“brainwashed” member of the most threatened groups would consent to that insurgency, which implies that the hypothetical or counterfactual criterion is satisfied. Furthermore, because not everyone is “brainwashed” and the insurgency would be a war against something like a holocaust against the future, and thus against a serious individual rights infringement (on the same scale as mass murder), only a single non-“brainwashed” member of the most threatened groups would have to consent according to Parry’s criterion. Hence, if further conditions are satisfied, then either criterion would justify a hypothetical climate insurgency. That further conditions are satisfied is doubtful, however.

Proportionality, necessity, and the probability of success

According to the Principle of Necessity a climate insurgency is only justified if its aims – or something sufficiently like it – cannot be established by other, less harmful means. I have severe doubts that a peaceful solution to the climate crisis is possible. Those who stand to gain most from continuing the status quo will be dead before the worst effects of climate change affect them (partially thanks to the fact that they can buy protection) and, therefore, a preventing climate disaster is not in their (financial) interest. And given their stranglehold on the rest of society, they will not be removed easily. Nevertheless, according to this principle, insurgency should be a last resort, and thus, until everything else that might work has been tried, insurgency is not justified. So, is there anything else that might work? (I don’t know. Let’s save that question for later.)

The Principle of Proportionality forbids war (or insurgency) if its harms outweigh its benefits. It is hard to estimate what the harms of a climate insurgency would be, but the harms a successful insurgency would prevent are immense. The global societal collapse we’re heading for will kill hundreds of millions, and if we don’t reduce CO₂ emissions soon, climate change will spiral out of control leaving space for only hundreds of millions or, perhaps, a billion of people on Earth.15 Hence, I’d say that a climate insurgency easily passes this principle.

Lastly, a war or insurgency is only justified if it has a reasonable probability of success. So, what’s the chance of a climate insurgency succeeding?

Zero, I think. Or very close, to zero.

What chance do a small number of climate insurgents (who are restricted by what was written in the section on Jus in Seditione) against a well organized enemy that has nearly unlimited funds, controls virtually all resources, and that controls public opinion. Look back at the web of money, power, and death sketched before16 and despair. This is no David vs. Goliath scenario – it’s a few mice against an army of lions.

Conclusion

For a war or insurgency to be justified, it must satisfy all six criteria. A climate insurgency would satisfy most – but not all – of them. Let’s go over the list:

1. Just cause – yes (self-defense of the young and poor; defense of future generations; survival; avoiding or minimizing massive suffering);

2. Competent authority – yes (individual or even hypothetical consent is sufficient given what is at steak);

3. Right intention – yes (the “Lesser Dystopia”);

4. Reasonable prospects of success – no (the chance of success is close to zero);

5. Proportionality – yes (societal collapse and climate disaster would be even worse than war); and

6. Necessity – uncertain (perhaps there are alternative means; perhaps not).

Thus, in conclusion, climate insurgency is not morally justified because it has almost no chance of succeeding. This, of course, raises the question of whether that could change. If for some reason, the enemy is weakened to such an extent that a climate insurgency would have a good chance of success, would it then be justified? It is far from obvious that the answer to that question is “yes”, because in such a situation there would almost certainly be changes in other conditions as well. For example, if the enemy is weakened to such an extent that insurgency is likely to succeed, there may very well be less violent and thus less harmful means available to achieve something similar to the aims of the hypothetical insurgency, and thus, a insurgency would not satisfy the criterion of Necessity.

The War of Position

If what is stated in the previous concluding (sub-) section is right, then the justifiability of climate insurgency largely depends on the strength of the enemy – but possibly in a somewhat paradoxical way. If the enemy is too strong then insurgency is not allowed because it cannot succeed; if the enemy is weak, then insurgency is not allowed because almost certainly less harmful means would be available. It is important to recall at this point that insurgency is not the goal itself, but a mere means towards a goal, so this latter finding is not a problem. What matters is the prevention of climate catastrophe (as much as possible) – that is the goal. Insurgency is merely one possible means towards that goal, and it turns out that it is very unlikely to be an appropriate means.

But this also focuses attention on a key point: the pivotal issue is the strength of the enemy. No attempt to avert catastrophe can succeed without disabling the enemy first.

This reminds of Gramsci’s distinction of two stages in the struggle against “hegemony” (the collection of values and ideas that keep the ruling class and the state in power). The “war of manoeuvre” is the phase that most resembles an actual fight (i.e. a war or insurgency), but that “war” can only succeed if the right groundwork has been laid in the first phase, the “war of position”, which is much more like a war of ideas. The war of manoeuvre is an attempt to grasp power and/or to bring about one’s political goals. The war of position is the attempt to create the conditions to make that possible.17

In the struggle to avert climate catastrophe, the war of position must have two goals, however. One is indeed to change the hegemonic values and ideas, very much in line with Gramsci’s suggestion. But the other, and perhaps even more important goal (not in the least because it is necessary to make the first goal attainable18) is to undermine, disempower, and break up the enemy. That then, must be the main short term goal in the struggle for a future. And this can only start with identifying the enemy. It must start with raising public awareness of who is responsible for the situation we are in, of what they have done, and continue to do, of who is lying to us and why, of who sold out our children’s future for their short-term profit. It must start with feeding public anger directed at that enemy; with undermining the enemy’s power base; with attacking and separating its allies; and so forth.

The struggle to avert climate catastrophe is not some abstract fight against -isms, systems, or ideas, but is a war against a very real enemy. It cannot be won by focusing on the issue(s) and ignoring the enemy. It’s not a war against climate change, but a war against the people and institutions responsible for climate change. The sooner climate activists realize that, the better, because climate action cannot succeed if it continues to ignore the enemy.

Links to articles in this series:

No Time for Utopia – Series introduction. Against “ideal theory” and Utopianism.

On the Fragility of Civilization – Predicting global societal collapse within decades.

The Lesser Dystopia – What is necessary to avoid that collapse?

Enemies of Our Children – Who and what are preventing the necessary change of course?

The Ethics of Climate Insurgency – This episode.

The Possibility of a Revolution – Can a revolution establish the Lesser Dystopia?

The 2020s and Beyond – A scenario for the coming decades.

What to Do? – Some closing reflections on what we should and can do.

If you found this article and/or other articles in this blog useful or valuable, please consider making a small financial contribution to support this blog 𝐹=𝑚𝑎 and its author. You can find 𝐹=𝑚𝑎’s Patreon page here.

Notes

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_environmental_killings

- Naomi Oreskes & Erik Conway (2010). Merchants of Doubt: How a Handful of Scientists Obscured the Truth on Issues from Tobacco Smoke to Global Warming (Bloomsbury).

- See, for example: Nathaniel Rich (2019), Losing Earth: The Decade We Could Have Stopped Climate Change (London: Picador).

- But don’t the rich deserve their money? No. Most wealth is inherited, and all wealth is ultimately based in rent extraction – that is, in abusing the control over some resource or market to exhort exorbitant fees. No one ever got rich by working for it. No one ever got rich in a fair or honest way. When it comes to the rich, Proudhon was entirely right when he said that “all property is theft”. If the rest of society wants to survive in better-than-barbaric conditions, then they need to take back what the rich have stolen.

- For example, the amount of CO₂ emitted directly or indirectly by the global 0.5% richest people is roughly similar to the amount of CO₂ emitted by the global poorest 50%.

- For a good overview of Just War Theory, see: Seth Lazar (2016), “War”, Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- Jonathan Parry (2018). “Civil War and Revolution”, in: Seth Lazar & Helen Frowe (eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Ethics of War (Oxford: OUP): 315-335.

- For a good general introduction to Just War Theory, see: Lazar (2016), “War”.

- Or alternatively, Jus ad Rebellionem and Jus in Rebellione.

- See: A Note on the Psychology of Radicalization and Terrorism.

- And it is, of course, debatable whether that falls within the definition of “violence”.

- Parry (2018). “Civil War and Revolution”.

- Parry (2018). “Civil War and Revolution”: 329.

- See: Lajos Brons (2017), The Hegemony of Psychopathy (Santa Barbara: Brainstorm).

- See: Stages of the Anthropocene.

- See above as well as: Enemies of our Children

- See: Brons (2017), The Hegemony of Psychopathy, pp. 69-70.

- Mainly because of the enemy’s control of the mass media.