According to Karl Jaspers, philosophy arose in the “Axial Age” as a kind of critical reflection on myth and tradition. Nowadays, there is widespread agreement among historians of ideas that the notion of an “Axial Age” is itself a myth, but I think that the other part of Jaspers’ idea is right, that is, philosophy indeed originates in critical reflection on myth and tradition. This doesn’t mean that this defines the scope and purpose of philosophy, of course – as a “mature” discipline, philosophy mostly reflects on itself – but I believe that reflection on this idea about the origins of philosophy can produce some insights about the nature of philosophy anyway. The category “myth and tradition” is a bit vague, however, so that’s where we should start.1

“Tradition” is an especially vague – and much too broad – notion in this context: it includes rites and rituals, various customs and institutions, ways of living and making a living, and so forth. While some of these may have been object of philosophical reflection, many others (such as agricultural or building practices and customs) have rarely if ever been considered to be within its scope. For this reason, I propose to substitute the category “mythos” for “myth and tradition”. That may not seem particularly helpful at first sight, and indeed it wouldn’t be if we’d stop there. “Mythos” is merely a convenient label for a category of cultural phenomena, however, and it is those phenomena themselves that matter. The category includes myths, legends, religion, Wisdom (with a capital W), as well as “common sense” (among others – this is not intended to be an exhaustive list). 2 What these have in common is that they all are expressions, representations, or variants of the dominant and largely taken-for-granted ideas and values of a culture or society. They do so in (sometimes subtly) different ways, however, so it may be worthwhile to have a closer look at some of these aspects of mythos.

Myths and legends are narratives, of course, and can be approached from a literary point of view as well. As aspects of mythos it’s not their narratives that matter, however, but the claims about reality, society, the good (and the bad), and so forth that are embedded in or represented by these narratives. Religion and myth overlap, but so do all the other aspects of mythos (and mythos cannot be strictly separated from philosophy either – more about that below). A defining characteristic of religion is that it relies on supernatural claims and/or explanations, and this is also a common characteristic of myth.

Wisdom and “common sense” may be the most controversial aspects of mythos. I’m not referring to wisdom in a general sense (i.e. the virtue of σοφία, 知, or prajñā) here, but to something like “the tautological emptiness” which is “exemplified in the inherent stupidity of proverbs” as Slavoj Žižek introduced the notion is his usual unsubtle way.3 “Wisdom” in this sense refers to claims that seem profound, but that upon closer inspection turn out to be problematic in some or (usually) all of the following ways: (i) they are extremely ambiguous and can (thus) be (re)interpreted in (very) different ways; (ii) they are tautological, platitudinous, meaningless, or self-contradictory (but their ambiguity and slipperiness allows constant reinterpretation and goal-post-shifting away from this conclusion); (iii) they are merely proclaimed and not supported by any kind of evidence or substantial argument.

“Common sense”, finally, is nothing but the thoughtlessly accepted vulgarization of myth, religion, and Wisdom of a culture or society. Mythos determines the limits of thought, of what can be sensibly thought, of what makes sense, and thus, of common sense. Rejecting the inherent claims of mythos – without explicit argument and/or evidence – leads to “non-sense”.

As mentioned in passing above, my short list of aspects of mythos is not intended to be exhaustive. There may be other aspects that fit in the same category. What makes something part or aspect of mythos is (a) that it (implicitly or explicitly) makes claims about the world/reality, about truth/knowledge, about good/evil, and/or what is/isn’t valuable in some other sense; (b) it does so without supporting those claims with evidence or (substantial) argument; and (c) it is widely accepted in a society or culture.4 Mythos, then, is/provides the shared background beliefs of a society or culture, and as such, the notion is closely related to “ideology” (in the Marxian sense of that term) and “hegemony” (or “cultural hegemony”). Ideology is mythos that serves the interest of a social class (usually the dominant/ruling class); hegemony is mythos that supports power and the sociopolitical status quo, and that (thereby) serves the interest of the ruling elite.

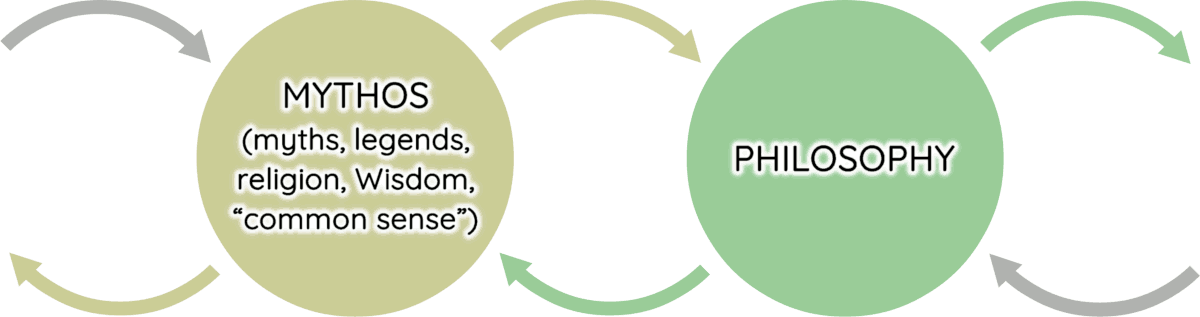

Philosophy originates in critical reflection on mythos. This is neither a definition of “philosophy”, nor a description of what it is or should be today. It is merely a historical claim. (And given that I’m not going to defend or support this claim, perhaps it should be classified as an attempt at Wisdom in the sense explained above.) The following picture is an extremely simplified representation of the relation between mythos and philosophy, but by looking into what it shows and what it simplifies or abstracts away, a more accurate picture can be sketched.

1) Philosophy is not the only intellectual enterprise that takes mythos as its object (and mythos is not philosophy’s only target either). Mythos can be studied in a variety of ways: sociologically, psychologically, historically, literary, and so forth. What distinguishes those approaches from the philosophical approach is that they ask very different questions: “Why is something claimed, believed, or accepted?” “How did that idea spread and where did it come from?” “Why is something expressed in this way rather than in another?” While these questions can also be of interest to philosophy, they are not philosophical questions. Philosophy is not so much concerned with why something is claimed, or by who, or other circumstantial factors, but whether the claim is true and/or whether it can be backed up by a good argument or evidence. (Notice that this is not a sufficient condition.)5

1) Philosophy is not the only intellectual enterprise that takes mythos as its object (and mythos is not philosophy’s only target either). Mythos can be studied in a variety of ways: sociologically, psychologically, historically, literary, and so forth. What distinguishes those approaches from the philosophical approach is that they ask very different questions: “Why is something claimed, believed, or accepted?” “How did that idea spread and where did it come from?” “Why is something expressed in this way rather than in another?” While these questions can also be of interest to philosophy, they are not philosophical questions. Philosophy is not so much concerned with why something is claimed, or by who, or other circumstantial factors, but whether the claim is true and/or whether it can be backed up by a good argument or evidence. (Notice that this is not a sufficient condition.)5

2) Mythos and philosophy do not (necessarily) differ in what they claim – the difference is methodological more than substantial. Both mythos and philosophy make claims about what kinds of things exist, about what’s true and what’s false and how we can know, about what matters and what is valuable, about the right thing to do or the kind of person to be, and so forth. These kinds of claim is typically considered to be “philosophical”. The first is metaphysical or ontological; the second epistemological; the third and fourth axiological and ethical or moral. However, it isn’t the substance of a claim that makes it philosophy or mythos; what matters is the claim’s context. If it is an implicit part of a story rather than an explicit claim, it’s probably mythos. If it is proclaimed without evidence or argument, it is Wisdom (especially if it is proclaimed in a vague or ambiguous and seemingly profound way). If it is generally and uncritically assumed to be true by the members of a culture or society, it is “common sense”. What distinguishes philosophy from mythos is that it doesn’t take such claims for granted, but critically inspects them and asks “Is this true?” “Is there evidence for this claim?” “Can it be supported by an irrefutable argument?” or something very similar. The key difference between mythos and philosophy is that between uncritical acceptance and critical scrutiny. (However, it must be taken into account that the extent of scrutiny and the standards for good argument and evidence themselves develop in the process of critical reflection, and that these standards may to some extent differ from tradition to tradition.)

3) There is no sharp boundary between philosophy and mythos. This might not be obvious – especially given the figure above – but it follows from the previous point. “Being supported by evidence or argument” or not is not a dichotomy. Rather, a claim is supported to greater or lesser extent. Proclaiming something without evidence or argument is Wisdom; extensively supporting it with reasonable arguments that result from (self-) critical reflection is philosophy; but there is much in between. Furthermore, it may not always be clear whether a claim is the result of critical reflection and argument or merely proclaimed, so it may be the case that claims made in a text appear more like Wisdom even though the author actually had very good arguments for making those claims. (The need to clearly express arguments or evidence is only there in case a view needs to be defended against opponents who recognize the relevance of argument and evidence.) In that case, the text should probably be classified as “Wisdom” and its author as a “philosopher” (but I don’t think this is very important).

It’s easy to find examples of such in-between cases in all three great philosophical traditions, but they are probably all controversial. In case of Western philosophy, the pre-Socratic philosophers and some (but not nearly all!) continental philosophers seem examples of Wisdom more than philosophy to me. In case of China, Laozi and possibly Confucius are – at least in my opinion – much closer to the Wisdom end of the spectrum than to the philosophy end, while Mozi, Mencius, and Xunzi, for example, are clearly philosophers. In case of India, the teachings of the Buddha as expressed in the Pāli canon are mostly more like Wisdom than like philosophy,6 while Nāgārjuna’s and Dharmakīrti’s most famous writings are obvious examples of philosophy. (The parenthetical note at the end of the previous point may partially explain why the recorded saying of Confucius and the Buddha appear more like Wisdom than philosophy: they stand at the beginning of traditions.)

4) Mythos and philosophy always interact and never separated completely. (Which is not top say that they cannot separate. More about that below.) Philosophy as critical reflection on mythos obviously takes ideas from mythos, but there is also influence in the other direction. Ideas developed by philosophers can become part of mythos.

The non-separation of mythos and philosophy also implies that a philosophical tradition cannot be fully be separated from its affiliated mythos. This might be obvious in case of Buddhist philosophy, for example. Buddhist philosophy and Buddhism or Buddhist mythos are obviously closely related and have influenced each other throughout history. The same is true in case of Western philosophy, however. From the Middle ages until modernity, Western philosophy is Christian philosophy and cannot really be separated from the Christian tradition that develop alongside it. Western philosophers tend to think of Descartes or Berkeley as philosophers simpliciter while Nāgārjuna and Dharmakīrti are Buddhist philosophers, but this nomenclature is really the product of a kind of blindness for the mythos of one’s own tradition (and/or of Western/white supremacism) – Descartes and Berkeley were Christian philosophers.

5) Mythos and philosophy also interact with other parts/aspects of their environment (including science and the mythos and/or philosophy of other cultures). This should be fairly obvious, but it is worth pointing out some of these interactions. I mentioned above (in parentheses) that asking whether the claims of mythos are true is not a sufficient condition for philosophy. The reason for that is that this kind of question could also be taken to define much of (the rest of) science. Science and philosophy are closely related, but the nature of that relation differs between ages and between traditions. In case of the West, most of the sciences developed as off-shoots of philosophy, while in case of China and India, it appears that science was more closely affiliated with technology than with philosophy.

There is also disagreement among philosophers about how to conceive of the distinction between (Western) philosophy and science today. W.V.O. Quine and a few others have argued that philosophy is one of the sciences, while many other philosophers see science and philosophy as two different kinds of enterprises. I think that Quine was right and that what sets apart philosophy from the other sciences is primarily methodological. Reasoning in philosophy is almost exclusively deductive, while the other sciences – with the exception of mathematics – rely heavily on inductive reasoning. This also implies that I don’t think that there are strict or clear boundaries between philosophy and the theoretical branches of various sciences. There is no strict or clear boundary between theoretical psychology and the philosophy of mind, for example, or between theoretical physics and metaphysics.

Another – and possibly even more important – kind of interaction is that of mythos and philosophy with another mythos (or another philosophy). Christianity is an interesting example hereof. The Christian mythos or mythoi was/were originally based on a Jewish mythos, but then adopted many elements of ancient Greek thought. Bart Ehrman has convincingly argued that Christian notions of the soul, heaven, and hell are of (Platonic) Greek origins and where almost certainly not things that Jesus believed in, for example.7 The Christian mythos as it developed and crystallized in the centuries after Jesus, then, was heavily influenced by Greek and Roman mythoi (and philosophies, perhaps)

6) Philosophy also (and increasingly) reflects on itself. While mythos changes due to external influences (which do not just include intellectual influences, but also other kinds of circumstances and changes therein), philosophy also changes due to reflection on itself. Philosophy originates in the critical reflection on mythos, but increasingly it turns inwards and starts reflecting on the claims and ideas of other (earlier) philosophers. It is this self-reflectivity of philosophy that makes transplantation from one mythos to another possible. Western philosophy started as the critical reflection on the ancient Greek mythos, but this was eventually replaced with a Christian mythos (which, as noted above, was itself heavily influenced by Greek thought, making the transplantation a lot easier), and more recently with a “modern” mythos. Because mythoi change (in response to changes in their environment) there are no clear boundaries between these various mythoi and no clear identity criteria either. Furthermore, if there is no single hegemonic mythos, there can be multiple competing mythoi at the same time, which – to some extent – is the case nowadays. This kind of plurality of mythoi is no problem for a philosophical tradition that has turned inward and primarily takes itself as the object of reflection. It then is no longer its affiliated mythos that identifies it, but its own tradition. Arguably, something like this is the case for Western philosophy, which can no longer be identified as “Christian philosophy” (but see also the following two points).

7) When mythos is invisible, philosophy fails. Mythos is generally accepted “knowledge”. It includes the various beliefs people take for granted to the extent that they don’t even realize that they have those beliefs. When mythos is not confronted with competing mythoi and is not the object of philosophical scrutiny it is invisible exactly because it is taken for granted and uncritically accepted. Philosophy – at least in its early stages – makes mythos visible, albeit only to philosophers (and non-philosophers do not always appreciate that). When philosophy becomes overly self-referential it may lose sight of mythos, however, and philosophers may delude themselves, believing that they have somehow emancipated from or transcended mythos.

That is a mistake. Everyone has beliefs about the nature of reality, about what exists and what doesn’t, about what we can know and how we can come to know those things, about what is right and what is wrong, and so forth. Such metaphysical, epistemological, ethical/moral, and related ideas are either provided by mythos or by philosophy (or by some combination of the two). If they are unconsciously, unthinkingly, unreflectively accepted, then their source is mythos. Western philosophy, which has largely transcended the Christian mythos, may not have emancipated from mythos altogether. There is a modern, Western mythos based on a mixture of myths and other beliefs about economics, politics, human nature, what is normal and what isn’t, the good and the valuable, and so forth that to a greater or lesser extent influence people’s (including philosophers’) ideas. The exalted status of happiness, autonomy, freedom, and so forth are not neutral or universal ideas, but are part of the modern mythos, for example, and so is the widely shared idea that there is no real alternative for the current socio-economic order (i.e. neoliberal capitalism). Of course, not every aspect of the modern mythos is accepted by everyone – in the contrary – but there is such a set of myths, “common sense” values and ideas, and morsels of “Wisdom” that forms the background of most (if not all) modern thought. And that mythos is affiliated with Western philosophy – some (critical) philosophers are aware of the modern mythos and reflect on it; others appear unaware and uncritically accept it; but no one (?) is fully independent from it.

Mythos likes to hide, and this has important implications. A good illustration (in my opinion, at least) is the kind of “secular Buddhism” propagated by Stephen Batchelor and others. As a tradition, Buddhism consists of Buddhist mythos plus Buddhist philosophy, but Batchelor rejects the latter and much of the former. In fact, he claims to reject all metaphysics, epistemology, and other philosophy. This is a mistake, of course. To reject explicit metaphysical, axiological, etcetera theorizing means to implicitly accept the dominant, common-sensical metaphysics (etc.) of the mythos of one’s culture, and this indeed is what Batchelor does. What he presents as “secular Buddhism” (or “Buddhism 2.0”) is based almost entirely on a neoliberal mythos of autonomous, self-dependent, self-improving individuals striving for (nothing but) their own happiness. He then dresses this neoliberal vision in “Buddhist” garb by selecting and (often radically) reinterpreting fragments of Buddhist Wisdom (from the Pāli canon) that (can be made to) fit his ideas.8 (The rest he discards as inauthentic or irrelevant because it was part of the mythos of the Buddha’s culture. He doesn’t use that term, of course, and neither is he aware that he is just as much under the influence of a mythos as the Buddha was.) Whether the result is “secular” is debatable, but it’s surely a stretch to call it “Buddhism”.

8) Only philosophy without mythos is “philosophy” without adjective. Western philosophy has not fully emancipated from the dominant mythos of Western culture, and probably never will. That doesn’t mean that it is fundamentally impossible for philosophy to become independent from mythos, however.

Mythos plays two roles in philosophy: one explicit and one implicit. The explicit role is that of an object or target of reflection; the implicit role is that of a source of unconsciously and uncritically accepted values and ideas.9 Separation of a philosophical tradition from its affiliated mythos would require it to become aware of the unconscious influence of mythos, to unmask mythos and make it an explicit object of critical reflection. This would only enlarge the explicit role of mythos in a philosophical tradition, however, and thus not sever the link. And because giving up on critical reflection of mythos amounts to enlarging the second (unconscious, uncritical) role of mythos, the only other option is to further expand reflection. Rather than associate itself with just one mythos, it would have to make all mythoi target of critical reflection, and thereby associate itself with none.

This is difficult, of course, and may very well be impossible in practice, but I think it is an ideal worth striving for. It is – in my opinion – what “philosophy” should be. It is the only kind of philosophy that deserves the name “philosophy” without an identifier (like “Western”, “Confucian”, or “Buddhist”) linking it to its affiliated mythos.

There’s a further problem that frustrates the emancipation of philosophy from mythos, however, and that is that the traditional aim of philosophy is – more or less – to replace mythos. Mythos includes or provides the uncritically accepted beliefs about reality, knowledge, the valuable, and the good (etc.) of a culture or society. These beliefs are unconsciously accepted (by most people) as absolute, universal, and certain truths (or certain knowledge). Philosophy critically reflects on mythos, but its traditional purpose is the same: to provide certain knowledge. Or in other words, philosophy merely aims to substitute its own certain truths for those of mythos. So, while traditional philosophy rejects mythos’s claims of absolute and certain truth, it very much believes in the idea of certain truth itself. (Skepticism seems a counterexample, but skeptics still accept that the quest for certain truth is the purpose of philosophy. They just claim that this quest is doomed to fail and – somewhat paradoxically – tend to find comfort in their belief that it is a certain truth that we cannot know anything else with certainty.) My point is that philosophy cannot really emancipate from mythos as long as it implicitly accepts a purpose that mirrors mythos. To break the bonds between philosophy and mythos, philosophy needs to ally with science instead.

Contrary to mythos and traditional philosophy, science does not claim certainty (or certain knowledge, certain truths, etcetera). Science accepts provisionally whatever is best supported by evidence and argument, while accepting that any scientific claim or theory may at some point be refuted by counter-evidence. Nothing is ever absolutely certain. Certainty is the domain of mythos, but that certainty is delusional, because if mythos is ever right, it is only right by accident. Like the rest of science, philosophy without mythos – that is, “philosophy” simpliciter – provisionally accepts whatever is best supported by evidence and argument, while acknowledging that nothing is immune to counter-evidence (at least, in principle).10

Scavenger Philosophy

Mythos has little philosophical value – at least from the perspective of “philosophy without adjective”. The ideas that make up mythos (by definition) lack epistemic justification, and if knowledge is something like justified true belief,11 then mythos cannot be a source of knowledge. Given that philosophy aims for knowledge of one kind or other, this makes mythos relatively useless. “Relatively”, for three reasons. Firstly, there is no sharp boundary between Wisdom and philosophy, and to a lesser extent the same is true for the boundary between other parts of mythos and philosophy. Secondly, mythos can – in principle – be a useful source of hypotheses, hunches, metaphors, examples, illustrations, and so forth. However, anything can be a source of those, really, and focusing on a single source can only lead to bias. Consequently, if mythoi are to serve this role, the greater the variety in mythoi that are mined for ideas (etc.), the better.

Furthermore, roughly the same applies to philosophical traditions. If focusing on a single source leads to bias, then all philosophical traditions are biased (given that they all originate in the reflection on one mythos or a very small number of mythoi), and are, therefore, not reliable sources of knowledge. (And if something isn’t a reliable source of knowledge, it is debatable whether it is a source of knowledge at all.) This doesn’t mean that all traditional philosophy should be discarded, however. (That would just be silly.) But it does suggest a change in attitude.

The dominant metaphor used to describe what a philosopher should do when she brings two or more philosophical traditions together is “dialogue”. I doubt that this is an appropriate metaphor, however . It presupposes that the person conducting this “dialogue” has the ability to honestly and accurately voice both sides in the debate and simulate the dialectical process towards agreement between these two sides, and it denies the researcher herself an active role in the debate (other than that of mediator). This requires more from that researcher than what can be reasonably expected, but is also deceptive: it is the researcher who decides the terms and questions, who selects and weighs the arguments, and who derives the conclusions. Hence, the actual practice is nothing like a dialogue (not even like an internal one).12

Moreover, there is another problem with the “dialogue” metaphor. By aiming for agreement or common ground, the two (or more) sides themselves are more or less exempt from scrutiny and critique. The “dialogue” is pre- and interceded with respectful (or even reverential) exegesis (even though it is rarely equally fair to both sides), and thus, the “dialogue” approach tends to be uncritical (or only critical of one side, due to bias of the philosopher conducting the pretend “dialogue”). If philosophical traditions (due to their affiliation with mythos) are inherently flawed and biased, however, they are undeserving of this respectful (or reverential) treatment.

The “dialogue” metaphor misrepresents actual, possible, and ideal philosophical practice all at the same time, and for that reason, it should be retired. A more useful metaphor is that of a scavenger: rather than simulating a pretend dialogue in her head, the researcher scavenges the carcasses of various philosophical traditions for digestible bits (i.e. bits she can use).

It must be emphasized here that “scavenging” is not the same as eclecticism. A scavenger that carelessly eats whatever it finds and that looks attractive at first sight will soon die of food poisoning or disease. Similarly, a philosophical scavenger that carelessly tries to incorporate any fancy idea she stumbles upon into her overall philosophy will sooner or later find that she has created an incoherent mess. (Her philosophy “died of food poisoning”.) A scavenger looks for the edible bits – that is, the pieces of meat it can digest, or in other words, the bits that provide valuable nutrients and keep it alive or even make it stronger. Similarly (again), a philosophical scavenger looks for the ideas that fit her philosophy, contribute to it, and (preferably) make it stronger. In the metaphor of “scavenging”, inedibility is the analogue of incoherence.

A few paragraphs back I wrote that there are three reasons why mythos is only relatively useless, but I only mentioned two. If a scavenger has repeatedly found that a certain type of carcass tends to have many edible bits, then this gives it a good reason to be more confident that a newly encountered carcass of that type will prove to be nutritious, as well as to prefer that type of carcass when it has a choice. Something like this applies to a philosophical scavenger as well. If a philosopher has repeatedly found valuable ideas in the work of a certain philosopher, or in a certain school of philosophy, or even in a certain mythos, then this gives her good reason to be more confident in the value of a new idea encountered in/from that same source. This is the third reason why (and how) mythos can be useful. There are some rather severe limitations on this kind of use, however.

Buddhist epistemology recognized only two sources of knowledge: perception and inference (or reason). This means that testimony (i.e. learning something from someone else or from a text) is not a source of knowledge in itself, and thus that even sūtras, which are supposed to contain the actual teachings of the Buddha, do not convey knowledge in themselves. Nevertheless, according to Dharmakīrti (the most brilliant and most influential of the Buddhist epistemologists) we are justified to (provisionally?) accept something from testimony (i.e. something we learn from a text/scripture or someone else) in certain circumstances. Jonathan Stoltz summarizes these as follows:

If a statement can be established empirically (through perception) or through ordinary (nonscriptural) inferential reasoning, then such a statement is not one that should be established through scripturally based inference [i.e. from testimony]. … Dharmakīrti goes on to state that a threefold analysis is to be applied to the scripture, s, from which one wishes to draw a scripturally based inference: (a) s cannot be contradicted by ordinary perception. (b) s cannot be contradicted by ordinary inferential reasoning. (c) s cannot contain any internal contradictions with respect to its pronouncements on radically inaccessible matters13.14

Notice that this is a threefold coherence criterion and that it supplements two other criteria: to (provisionally?) accept some knowledge from testimony, (1) one must have reasons to trust its source, (2) the idea in question must be something that cannot be inferred, perceived, or inferred from perception, and (3 to 5) it cannot be incoherent in three different ways – that is, (3/a) it cannot be incoherent with perception, (4/b) it cannot be incoherent with inference/reason (and thus with all other inferential knowledge), and (5/c) it cannot be incoherent internally (i.e. it cannot consist of parts or sub-claims that contradict each other) and neither can it be incoherent with anything else accepted on the basis of these same criteria. These are the same criteria that a philosophical scavenger applies to test whether she can accept an idea into her system, regardless of whether the source of that idea is philosophy, mythos, or something else.

What must be realized, however, is that with the growth of scientific knowledge, the domain of statements/ideas that cannot be established through perception, inference, or a combination thereof (i.e. “radically inaccessible matters”) has shrunk considerably, and possibly has disappeared entirely. Nevertheless, while there may not be many “radically inaccessible matters” anymore, there certainly is much knowledge that is contingently inaccessed by any individual philosopher. No one knows everything, and the more we know collectively, the harder it gets individually to even know a significant percentage of that collective knowledge. Trying to learn everything is humanly impossible, and often the second-best – and only practically available – option is to trust a source that has proven to be reliable in the past. Although mythos is not a likely trustworthy source, a mythos-based philosophy can very well be.

There’s another aspect of the scavenger metaphor that is worth emphasizing: not everyone can be a scavenger. There also needs to be a steady supply of carcasses the scavenger can feed on. Hence, there need to be diseases and/or predators providing those carcasses, and prey animals in the latter case. My point is that scavenger philosophy cannot (and should not) be the only approach to philosophy (or even the only legitimate or commendable approach). It is merely the only approach that is deserving to be called “philosophy” without an identifying adjective (like “Western”, “Chinese”, “Buddhist”, and so forth). However, it depends (again) on “a steady supply of carcasses”, and those “carcasses” are supplied by specialists in Buddhist philosophy, African philosophy, analytic philosophy, and so forth.

But scavenger philosophy can also become partially self-referential, of course, like all other philosophical traditions (see point 6 above). Scavengers can dine on the carcasses of other scavengers. Whether those prove to be nutritious remains to be seen. There aren’t enough philosophical scavengers around yet to judge. From the perspective of a scavenger – let’s say a vulture – by the way, this article is the equivalent of something like a dead cockroach, so there certainly isn’t much to scavenge here. I’m sorry for wasting your time. But just in case there is anything here you can use, scavenge it; leave the rest to rot.

If you found this article and/or other articles in this blog useful or valuable, please consider making a small financial contribution to support this blog, 𝐹=𝑚𝑎, and its author. You can find 𝐹=𝑚𝑎’s Patreon page here.

Notes

- Jaspers didn’t use this category “myth and tradition” as such, by the way, so he can’t be blamed for this exact vagueness. I have used it myself on a number of occasions, on the other hand.

- Wiktionary gives four meanings of “mythos”. The first three are all relevant to the way I’m using the term here. (The fourth is about the concept of “mythos” in literature, which is a different notion.) “1) Anything transmitted by word of mouth, such as a fable, legend, narrative, story, or tale … 2) A story or set of stories relevant to or having a significant truth or meaning for a particular culture, religion, society, or other group; a myth, a mythology. 3) (by extension) A set of assumptions or beliefs about something.”

- Slavoj Žižek & F.W.J. von Schelling (1997), The Abyss of Freedom / Ages of the World (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press), p. 71.

- In case of myths and legends, this doesn’t necessarily mean that their narratives are widely accepted as literally true, but that the claims about reality, truth, or the good that are implicitly made or expressed through those narratives are widely accepted.

- Notice that this can be interpreted to mean that the history of philosophy is not itself philosophy. This is a controversial claim, but I think it is correct. The history of physics isn’t physics. I don’t see why this would be any different for philosophy.

- “Mostly”, because occasionally a claim is backed up by argument.

- Bart Ehrman (2020), Heaven and Hell: A History of the Afterlife (London: One World).

- More or less this point is also made (and much better supported) in: Philippe Turenne (2021), “Buddhism without a View: A Friendly Conversation with Stephen Batchelor’s Secular Buddhism”, in: Richard Payne (ed.), Secularizing Buddhism: New Perspectives on a Dynamic Tradition (Boulder: Shambhala): 185-205.

- In continental philosophy, the explicit role of mythos is probably more important than the implicit role. In analytic philosophy it is the other way around.

- The most prominent advocate of this understanding of the nature and methods of philosophy is W.V.O. Quine. It is sometimes called “Quinean Naturalism”.

- “Something like” because a further element to the definition might be necessary to fix Gettier cases, or “justified” might have to be replaced with “reliably formed”, for example. None of that matters here, however.

- I have written this before in a note to the extended version of my book review of Jay Garfields’s Engaging Buddhism. The suggestion for an alternative approach, further developed here, was also first suggested in that note.

- ”Radically inaccessible” means that they cannot “ be established empirically (through perception) or through ordinary (nonscriptural) inferential reasoning”.

- Jonathan Stoltz (2021), Illuminating the Mind: An Introduction to Buddhist Epistemology (New York: OUP), p. 104.