In a review of a number of books about the Anthropocene, British sociologist Leslie Sklair wrote that:

Three main narratives have emerged:

(1) While posing problems, the Anthropocene is a ‘great opportunity’ for business, science and technology, geoengineering, and so on.

(2) The planet and humanity itself are in danger, we cannot ignore the warning signs but if we are clever enough we can save ourselves and the planet with technological fixes (as in 1).

(3) We are in great danger, humanity cannot go on living and consuming as we do now, we must change our ways of life radically – by changing/ending capitalism and creating new types of societies.1

These three narratives correspond to different attitudes towards climate change and its effects. The first is optimistic, while the second and especially the third are much more concerned.

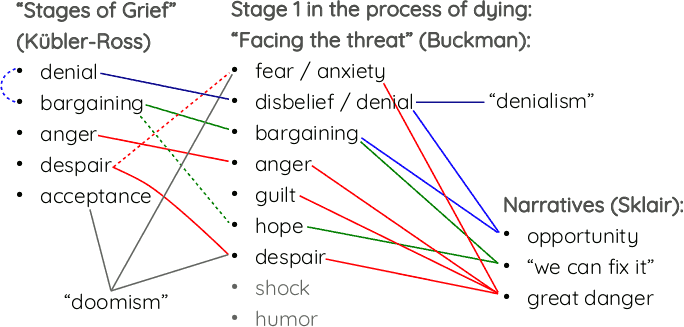

Given the rather obvious analogy between climate science and disease (albeit on a planetary rather than personal scale, and with humans as the causes rather than as the patients), another way to look at attitudes towards climate changes is through the lens of Elisabeth Kübler-Ross’s famous “stages of grief”.2 Kübler-Ross suggested that terminally ill patients go through a number of stages: denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance. Parts and aspects of her theory have been refuted, however, patients don’t necessarily go through all these stages in order – reality is a lot messier. And other theories have been suggested.3

In an overview of theories of (human responses to) death and dying, Gina Gopp attributes an updated stage model to Robert Buckman.4 In the first stage of that theory, the patient responds to the diagnoses (or “faces the threat”) with a mixture of emotional reactions including fear, anxiety, shock, disbelief, anger, denial, guilt, humor, hope, despair, and bargaining. Acceptance – missing from this list – is stage three, but this stage is not necessarily reached by all patients.

There are interesting links between Kübler-Ross’s stages and Buckman’s list of reactions when “facing the threat”. And further connections can be made with Sklair’s three “narratives” about climate change mentioned above. The following diagram illustrates this.

Denial and bargaining (top left) are closely related, as bargaining is based on a denial of the seriousness of the “disease”. Both denial and bargaining also appear in Buckman’s list, and the same is true for anger and despair. Acceptance is missing from Buckman’s list, of course, as that attitude characterizes his third stage and only initial stage reactions are listed here. Various reactions/attitudes are also linked to Sklair’s narratives about climate change in the bottom right, and lines are color coded according to which of Sklair’s narratives they connect.

Denial and bargaining (top left) are closely related, as bargaining is based on a denial of the seriousness of the “disease”. Both denial and bargaining also appear in Buckman’s list, and the same is true for anger and despair. Acceptance is missing from Buckman’s list, of course, as that attitude characterizes his third stage and only initial stage reactions are listed here. Various reactions/attitudes are also linked to Sklair’s narratives about climate change in the bottom right, and lines are color coded according to which of Sklair’s narratives they connect.

The first of Sklair’s narratives sees climate change as an opportunity, and is characterized by denial and bargaining. Bargaining, but not denial (!), is also an aspect of his second narrative, which can best be characterized as an optimistic “we can fix it” attitude. The key reaction to the “disease” (i.e. climate change) in this attitude is hope (which is, itself linked to bargaining, as the latter only makes sense if one has hope). The third of Sklair’s narratives, which stresses the gravity of the situation we are in, is closely related to fear/anxiety, guilt, and despair, but is, perhaps, most strongly associated with anger.

Two narratives or attitudes are missing in Sklair’s list, but can easily be added and connected with Kübler-Ross’s stages and Buckman’s emotional reactions. The first is climate change denial or “denialism”. The second is “doomism”, the most apocalyptic of all attitudes towards climate change, which is related to fear, despair, and acceptance. Denialists differ from Sklair’s “opportunity” narrative in that they don’t even see climate change as an opportunity, but deny that anything is wrong altogether – or if something is wrong, it is a minor thing that will automatically correct itself soon, and that is not caused in any way by humans. Doomists differ from Sklair’s “great danger” narrative in that the latter believe that catastrophe still can be avoided – even though it would require major changes – while doomists believe that it is already inevitable. According to doomists, human civilization will collapse (relatively soon), and humanity might even go extinct.

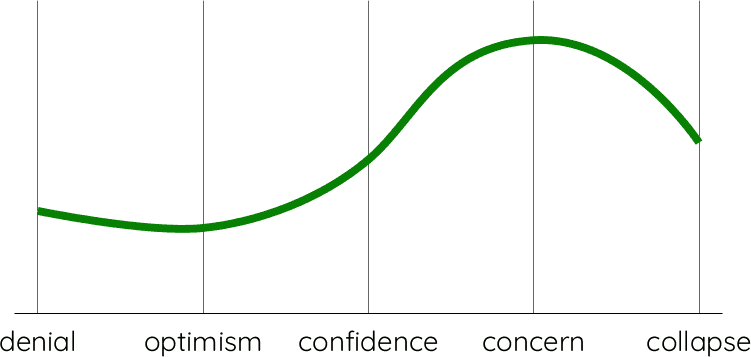

The five different narratives of, and attitudes toward climate change can be labeled and characterized as follows:

1 – denial : climate change isn’t happening or isn’t a problem.

2 – optimism : climate change isn’t a serious problem, and offers great opportunities for business and technology.

3 – confidence : climate change is a serious problem, but we can fix it by means of technology and some minor social adaptations.

4 – concern : climate change is a very serious problem that cannot be fixed by technological means, but requires major social changes.

5 – collapse : climate change will lead to societal collapse or even human extinction, and there is nothing we can do to avoid this.

These aren’t clearly separated categories, however. Rather, intermediate positions are possible. For example, I’d locate myself in the concern category, but closer to the collapse end than to the confidence end because I believe that while we can avoid collapse in principle, we won’t, because those who have money and power profit too much from the path towards collapse.5 Strictly speaking that doesn’t place me in the collapse category, however, because I do not believe that collapse is inevitable in principle. (Notice that I’m using small caps to refer to the attitudes/narratives and normal lower case letters when using the same word in its ordinary sense.)

Furthermore, the above diagram suggests that these five categories are (probably) internally heterogeneous for another reason: most of them are associated with multiple emotional responses, and there may be varieties that are characterized by a different emphasis. For example, the concern category may include sub-categories that are characterized by anger and despair, respectively. And similarly, there appear to be clearly distinguishable varieties of the collapse attitude some of which are primarily characterized by fatalist despair, while others seem expressions of something like Schadenfreude, or even of a Romantic desire for a clean sweep and a post-apocalyptic new world. On the other hand, some of the emotional responses appear to be almost defining characteristics. Anger is the most typical emotion associated with the concern narrative/attitude, while the confident narrative/attitude is strongly affiliated with hope. I don’t think there are similar catchwords for the other three, however.

truth and falsity of core beliefs

Nevertheless, more than by these emotional reactions, the five attitudes or narratives are defined by the propositions that summarized them above. These propositions represent the core beliefs of the five attitudes/narratives, and since propositions (by definition) are either true or false and not all of these propositions can be true (simultaneously), at least some of the five attitudes/narratives are founded on false beliefs. Denial is most obviously false, but the idea that climate change is an opportunity more than a danger, which characterizes optimism, is almost equally nonsensical.

In The Lesser Dystopia I argued that alternative sources of energy cannot possibly replace fossil fuels if energy consumption remains at anywhere near present levels, and consequently, that a drastic reduction in energy use is necessary. But such a drastic reduction would, however, lead to economic decline, which is impossible under capitalism, and thus, preventing catastrophe would also require an overhaul of the currently dominant economic system. But even that is not the end of the necessary changes. Agriculture is a major CO₂ emitter and needs to be transformed as well, and various industries (that use too much energy or pollute too much) need to be shut down. In other words, a realistic assessment of the energy situation and what depends on it reveals that mere technological change is insufficient, and thus that the confidence attitude/narrative is based on a false premise. (And consequently, the foundation of optimism is even further from reality.)

This, then, leaves us with concern and collapse. As mentioned above, I think that that collapse can – in principle – still be avoided, and thus that the core belief of the concern attitude/narrative is right, but I also think that the evidence is less clear here than in the other cases. Denial and optimism are obviously grounded on nonsense, and confidence is almost certainly also based on a false premise (that is, it fails to understand the true nature of our dependence on fossil fuels or makes naive assumptions about alternative energy), but I see no equally decisive evidence to arbitrate between the remaining two attitudes/narratives.

prevalence

An important question is how strong these various attitudes are in different social sectors, but unfortunately, there is no data (as far as I know) for clear and straightforward answers to that question. There are various ways to approach the question, however, depending on what sector one is focusing on.

In case of the sciences, the confidence attitude is the de facto norm. Most of the social sciences and humanities are effectively denialist, however, because they completely ignore climate change, but I doubt that explicitly denialist publications would be accepted by mainstream journals in these fields. A few denialist papers have been published in various journals, but that number is exceedingly small (and many of them have been debunked since6). The optimistic attitude is fairly common among specialists in geo-engineering, but this is an exception of the confident norm. The other end of the spectrum is taboo.

Both the concern and collapse attitude are common in more journalistic writings (and I have the impression that they are getting more common), but are not accepted in scientific journals. This is especially true for the collapse attitude. The only predictions of collapse allowed in academic journals are abstract, mathematical models that are mere theoretical exercises rather than concrete predictions.7 Academic writings that try to sketch more concrete scenarios of collapse are not accepted by scientific journals and are “published” as working papers or reports, if at all. For example, Jem Bendell published his famous “Deep Adaptation” as a working paper after it was rejected by a journal,8 and I did more or less the same thing with my paper “A Theory of Disaster-Driven Societal Collapse and How to Prevent It” after that was rejected twice. Another example is a paper by David Spratt and Ian Dunlop that got a lot of attention in the press, but that was only published as a “report” by a small Australian NPO.9 (For a discussion of their paper, see: Michael Mann vs. the “Doomists”.)

The picture appears to be a bit different in the arts and entertainment, but it is hard to find data to confirm this. In any case, climate change is not a topic in “serious” literature. As Amitav Ghosh writes in his The Great Derangement,

fiction that deals with climate change is almost by definition not of the kind that is taken seriously by serious literary journals: the mere mention of the subject is often enough to relegate a novel or short story to the genre of science fiction. It is as though in the literary imagination climate change were somehow akin to extraterrestrials or interplanetary travel.10

According to Ghosh, extreme weather events and other effects of climate change are too “improbable” to be used as plot elements in serious fiction. In a sense, climate change is “unthinkable”, and therefore taboo in serious art. But it’s not in less “serious” art and in movies, of course. In the contrary, there is a whole genre focused on climate change, called “climate fiction” or “cli-fi” for short.

Unsurprisingly, there is no data about how cli-fi relates to the five attitudes towards climate change, so I read every synopsis of a cli-fi novel I could find on Wikipedia (hoping that that gives an at least somewhat representative sample of the genre) and tried to classify it. Because some authors had many books on Wikipedia while others were represented with only one book, I ended up classifying authors rather than individual books. The result is shown in the following graph (the Y-axis is unlabeled because this data is insufficiently reliable to assign exact scores):

Despite the unreliability of this data, the bump in the right part of the diagram is too large to be a mere artifact. Contrary to the sciences in which confidence is the official norm, cli-fi appears to be (increasingly?) trending towards the concern or even collapse scenarios. (Many cases appeared to be somewhat in between the two, in the same way that I locate myself more or less in between the two, by the way – that is, they predict collapse not because it is inevitable in principle, but because political and socio-economic circumstances make it inevitable.)

Despite the unreliability of this data, the bump in the right part of the diagram is too large to be a mere artifact. Contrary to the sciences in which confidence is the official norm, cli-fi appears to be (increasingly?) trending towards the concern or even collapse scenarios. (Many cases appeared to be somewhat in between the two, in the same way that I locate myself more or less in between the two, by the way – that is, they predict collapse not because it is inevitable in principle, but because political and socio-economic circumstances make it inevitable.)

One thing that struck me while doing this, is that cli-fi has roots in two other literary genres – science fiction and apocalyptic fiction or disaster stories (the latter genre may be more common in movies than in books; more about that below) – and that cli-fi novels with a more obvious science fiction orientation were closer to the optimistic (or even denialist) end of the spectrum, while those with a more obvious affiliation to apocalyptic art and literature tended towards the right on the graph. This shouldn’t come as a surprise, of course, as traditional science fiction tends to be very optimistic about the future, and much of it is characterized by high confidence in technology and a “we can fix it” attitude.

In “Popular Culture and the ‘New Human Condition’”, Ailise Bulfin discussed the proliferation of the theme of catastrophe (and post-catastrophe) in contemporary popular fiction, focusing on film and TV.11 She “argues that ecological disaster is one of the over-arching concerns for this era and that this is amply represented in current popular culture by the proliferating depictions of catastrophe, ecological and otherwise.”12 Hollywood disaster movies tend to be apocalyptic and fatalistic more than angry, however, suggesting that they are closer to the collapse attitude than to concern. Perhaps, this can be best explained by popular cinema’s role within hegemonic culture – that role has always been to promote acceptance rather than dissent.13 And consequently, as Bulfin writes, “Hollywood cli-fi films continue to present climate change in unhelpful ways, recycling the tropes of spectacular immediate catastrophe and the healing of interpersonal relationships among small groups of survivors, and therefore failing to present more realistic and instructive scenarios of successful collective action in the face of gradual climate change”.14 Hence, the dominant treatment of catastrophe in mainstream cinema illustrates what Michael Mann justly considers the main problem with “doomism” (i.e. the collapse attitude – see Michael Mann vs. the “Doomists”): fatalism promotes inaction and thereby safeguards the status quo (and those who profit from it) from activism and social change. Or in other words, “doomism” and collapse are harmless to the socio-economic elite, and therefore, harmful to everyone and everything else.

While I have the impression that climate journalism – especially in books written by journalists – has been gravitating towards the concern attitude/narrative, this certainly isn’t the case for the mainstream press. The extreme right wing of the mainstream press – that is, Fox News and its allies – have long been dominated by denialism, but that attitude is increasingly becoming a fringe attitude. It may seem that much of the mainstream press is still in denial in the same sense as “serious” literature and the social sciences are (see above), but neglect should not be mistaken for denial. Indeed, climate change is not an important topic (or not a topic at all) in most mainstream press, but that is not because it is denied but because of a widespread belief that “they will fix it” and thus that “we” can safely ignore it and leave it to the experts.

This “they will fix it” attitude may very well be the most widespread attitude towards climate change. It is an attitude of deference and inaction in which the only legitimate climate “activism” is voting and/or appealing to politicians and other authorities. It is an attitude of confidence and hope – namely the confidence and hope that they will fix it, in which “they” stands for the political and scientific authorities (i.e. politicians, scientists, engineers, economists, etcetera). This, thus, is the confidence attitude, even if it may superficially look more like a form of denial, but it is a form of confidence rooted in ignorance, blindness, and a sheepish trust in authority.

The picture that is emerging from the foregoing looks more or less like this:

- Highbrow parts of society such as the sciences and serious literature, but also the mainstream press, are dominated by the confident or optimistic attitudes. Denial is becoming fringe, although it is still tolerated (and sometimes even encouraged) in the mainstream press. Concern and collapse are taboo.

- In more lowbrow parts of society such as popular fiction (in film and writing) and non-fiction (i.e. climate journalism) the concern and collapse attitudes are becoming increasingly common. Nevertheless, the other attitudes also (still) occur, and the ignorant inactivism of the confident “they will fix it” attitude is probably by far the most common.

I’m not sure how long the latter will remain true, however. According to the 2017 report Climate Change in the American Mind,15 “four in ten Americans (39%) think the odds that global warming will cause humans to become extinct are 50% or higher” and another study from 2015 reports that “in four Western nations: the US, UK, Canada and Australia . . . a majority (54%) rated the risk of our way of life ending within the next 100 years at 50% or greater, and a quarter (24%) rated the risk of humans being wiped out at 50% or greater”.16 It seems then, that the collapse attitude is spreading fast.

One reason for this spread may be that the collapse attitude/narrative seems to speak to widely shared religious sensibilities and the human need for meaning (in/of life). Romi Mukherjee has argued that the “nihilistic embrace” of apocalypse is one of three “para-religions of the anthropocene”.17 (The other two are ecological humanism and eco-paganism.) And Robert Jay Lifton has suggested that “dark visions cast us in the role of potential survivors who . . . seek some kind of meaning in their ordeal. One such meaning is that it is already too late for us: climate change is rampant, irreversible, and more powerful than any antidotes we may bring to it”.18 By providing a coherent, overarching, more or less goal/end-directed narrative the collapse narrative/attitude provides new meaning in world that – due to climate change – lost its previous meaning(s).

a two-front war

From a mainstream – that is, confident or optimistic – point of view, both the collapse and concern attitudes are a threat, but for very different reasons. For the part of the mainstream that is closer to concern and genuinely wants to address the climate crisis – albeit not in a way that threatens the socio-economic and political status quo – the fatalistic collapse attitude is the main threat because it promotes passivity and inaction, which undermines their efforts to address the issue. For most of the mainstream, the angry and revolutionary concern attitude is much more dangerous, however, as concern seeks to radically overhaul society and undermine (if not sweep away) the foundations of the elite’s power and wealth. From a conservative perspective – regardless of whether that conservatism is rooted in an egocentric hunger for wealth and power, in ignorance, and/or in a fear of change – the collapse attitude is no problem, exactly because it promotes passivity, while the concern attitude is a major threat.

Despite the difference in interests and threats between these two sections of the mainstream, they are effectively allied. The alliance may be uneasy at times, but it is firmly rooted in a shared conviction that dealing with climate change should be left to experts and authorities, and in a shared desire to avoid major social, economic, and/or political changes. Furthermore, the alliance is also strengthened by the fact that concern threatens the established, mainstream environmental organizations (as well as established experts and authorities on the issue of climate change) as much as it threatens the rest of the establishment. (“Big nature” has made itself pretty much irrelevant by this alliance, however, but is too dependent on it to switch sides to concern.) Michael Mann, for example, who deserves nothing but the utmost respect for his work as a climate scientist, has become a tool of the mainstream alliance by his continuous attempts to undermine and de-legitimize concern by conflating it with collapse. It is rather unfortunate that he doesn’t seem to understand this, but by undermining concern he is harming efforts to respond to the climate crisis more than helping them, and at the same time he is (unconsciously?) helping established interests and elites. (See also: Michael Mann vs. the “Doomists”.)

But even without the help of Michael Mann, the fight against concern is relatively easy for the establishment. Through its control of the press it can redirect anger (at immigrants and refugees, for example – see The 2020s and Beyond), but what might be even easier, through repression and inertia it can change anger into despair. Or in other words, just by resisting change (and using whatever force necessary to do that) it can cause a steady stream of conversions from the dangerous (to them) concern attitude to the harmless collapse attitude. For concern, on the other hand, the battle is much harder. It is not just fighting on two fronts (against the establishment as well as against fatalist collapse), but the enemy on of those two fronts controls virtually all the weapons (i.e. the mass media) and all the money. Hence, from a tactical point of view, the first objective in that struggle should be to disarm the opponent as much as possible – that is, to destroy the opponents’ (control over) the mass media.

the nature of doomism

If hope turns to anger, people switch from confidence to concern; if it turns to despair, they switch to collapse. Unfortunately, despair seems to be winning out. There is something that puzzles me about the collapse narrative/attitude, however. This “puzzle” is suggested by an apparent parallel between the prospect of one’s own death and the prospect of the “death” of (one’s) civilization.

In an abstract, more or less detached way, most (or all?) people realize that they will eventually die. But in addition to that ordinary knowledge of one’s eventual death, there is also a state of shock associated with a sudden full realization that one is going to die. In ancient Buddhist texts this is called saṃvega. Western philosophers have called it by a variety of names – James Baillie most recently used the term “existential shock”.19 Baillie describes his own experience of this state as follows:

I entered into a state of mind unlike anything I had experienced before. I realized that I will die. It may be tomorrow, it may be in fifty years time, but one way or another it is inevitable and utterly non-negotiable. I no longer just knew this theoretically, but knew it in my bones. . . . It was as if the blinders had been removed, and I was the only person to have woken up from a collective dream to grasp the terror of the situation.20

In a forthcoming paper in the journal NeuroImage, Yair Dor-Ziderman and colleagues describe the neural mechanisms that shield the mind from this full awareness – that is, from saṃvega or existential shock – in normal circumstances, which is (as far as I know) the first evidence for the distinction between these two kinds of awareness of one’s own mortality that is not based on introspective and subjective experience.21

Saṃvega or existential shock is interesting for a number of reasons. Baillie was (and is) most interesting in an epistemological puzzle: How can I be shocked by something I already know? And to a large extent the research by Dor-Ziderman and colleagues answers that question (in a way that seems to be fairly similar to Baillie’s own answer). I’ve been more interested in another question, however. Supposedly, saṃvega or existential shock has certain psychological effects – it is said to be morally and religiously motivating in ancient Buddhist texts, but also in more recent Western writings – and it is not clear how and why exactly that would be the case. In “Facing Death from a Safe Distance”, I tried to answer this question.22

If the realization of the inevitable death of (one’s) civilization is indeed analogous to the realization of one’s own eventual death, then there should be a state similar to saṃvega, and that state might have comparable effects. This suggestion raises a number of questions, however: (1) Why would one think that the two cases are analogous? (2) Is there such a state of shock related to the realization of the inevitable death of (one’s) civilization? (3) What (if any) (psychological) effects does that state have? These three questions are the aforementioned “puzzle”. Let’s address them in order.

The reason the mind protects itself from the awareness of death is because death and the awareness thereof are threatening. If Ernest Becker and Samuel Scheffler are right, the (awareness of) the death of (one’s) civilization may be even more threatening, however. This is the main reason to think that the two cases might be analogous. The main counterargument is (probably) that it is unlikely that the brain processes involved in shielding the mind from death described by Dor-Ziderman and colleagues can play a similar role in shielding the mind from the awareness of civilizational death. That those processes do not play that role doesn’t imply that there is some other way in which the mind shields itself, however.23

According to Samuel Scheffler, “the actual value of our activities depends on their place in an ongoing human history” and “humanity itself as an ongoing historical project provides the implicit frame of reference for most of our judgments about what matters”.24 And consequently, in a doomed or dying world “people would lose confidence in the value of many sorts of activities, would cease to see reason to engage in many familiar sorts of pursuits, and would become emotionally detached from many of those activities and pursuits”.25 Scheffler’s point should become quite obvious upon a moment of reflection. What’s the point of writing a book or composing a symphony if civilization is collapsing or mankind is even going extinct? What’s the point of raising and educating children in a world heading for collapse? Without a future, very little matters, and without a future for mankind, almost everything that matters to us loses its value. It is for this reason that Scheffler claims that “the collective afterlife [i.e. the survival of mankind] matters more to people than the personal afterlife”.26

Scheffler’s argument about “the collective afterlife” appeals to the importance of some kind of “audience” for our products and actions. Hence, while he assumes that it is the survival of mankind in general that gives value to our activities, most of his argument only suggests that it is the survival of people that are sufficiently like us that matters.27 If his argument is adjusted for this oversight, we end up with something very similar to Ernest Becker’s argument in The Denial of Death,28, much of which has been empirically confirmed by psychologists working on “Terror Management Theory” (TMT). (But, rather oddly, Scheffler refers neither to Becker, nor to Terror Management Theory.)

According to Ernest Becker, much of civilization – religion especially – is a defense mechanism against the fear or “terror” of death. A civilization is an “immortality project” that allows me to become part of and contribute to something that survives my biological death and that thereby offers some kind of symbolic survival or eternal life. TMT operationalized, tested, and confirmed many of Becker’s ideas. According to the main theorists behind TMT, “the awareness of death gives rise to potentially debilitating terror that humans manage by perceiving themselves to be significant contributors to an ongoing cultural drama”, and “reminders of death increase devotion to one’s cultural scheme of things”.29 In other words, many of our activities and many of our beliefs are motivated by “terror management”, controlling the fear of death, and “effective terror management is faith in a meaning providing cultural worldview and the belief that one is a valuable contributor to that meaningful world”,30 and conversely, our ability to fend of the potentially debilitating fear of death depends on our confidence in the value and survival of the worldview and civilization to which we subscribe.31

In answer to the first question, then, personal death and civilizational death are (or may be) similar because they are threatening. Importantly, if Scheffler and Becker are right, then civilizational death is even more threatening than personal death, and if that is the case, one might expect that a full awareness of civilizational death has even stronger psychological effects than a full awareness of personal death. This brings us to the second and third questions: Is there a (saṃvega-like) state of shock related to the realization of the inevitable death of (one’s) civilization? And what (if any) (psychological) effects does that state have?

I have no (good) answers to these two questions, however. I’m fairly familiar with saṃvega (or existential shock) – I know how to bring it about (and how to prevent it), but I can only do that because I’m convinced that I will inevitably eventually die. I’m not equally convinced that civilization will perish (or collapse, but that is the same thing), however, and consequently, I doubt that using similar techniques could bring about a similar state about civilizational death. Saṃvega is a state of shock about something one already knows, but I do not know that civilization will “die” (even though I believe that it is unlikely that anything resembling civilization will remain by the end of the current century).

Furthermore, even if I would be able to bring about some kind of saṃvega-like shock about civilizational death, I would be very hesitant to try for reasons related to the third question. In “Facing Death from a Safe Distance”, I argued that the effects of saṃvega depend on two processes: an increase in mortality salience and an improved insight in (the nature of) suffering.32 Suffering, however, is inherently personal. A civilization itself does not suffer (except in a metaphorical sense, perhaps), only its members do. And consequently, this second process doesn’t apply to the analogous case. Furthermore, the first process doesn’t analogously apply either because the effect of mortality salience (i.e. the awareness of death) itself depends on one’s identification with something like a cultural worldview and on the continued existence of the culture or community associated therewith (which is exactly what civilizational death denies). Hence, if there is a saṃvega-like state related to the prospect of civilizational death or collapse and if that state does have certain (psychological) effects, then those effects are unlikely to be (very) similar to the effects of saṃvega. And consequently, we cannot rely on saṃvega as a guide to what those effects might be. An answer to the third question – what (if any) (psychological) effects does this supposed state of shock have – can, therefore, only be speculative. My best guess is that it leads to an elimination of the last glimmers of hope and to a state of utter despair. But this might be a state of despair bordering on insanity because – if Scheffler and Becker are right – it would radically sweep away the foundations of all value and make everything completely and utterly pointless. If that is right, it would be a state (much) worse than depression.

Given that reports of existential shock (or saṃvega) aren’t hard to find, I suspect that the phenomenon is fairly common. If that is the case, one would expect that its civilizational equivalent would not be exceedingly rare either among those who firmly believe that civilization or even mankind is really going to end soon. However, I have never read about or heard of anything even remotely like existential shock about civilizational collapse. Despair, fear, fatalism, anger, and so forth are all pretty common responses, but I have never encountered a report about a kind of shock with similar intensity as saṃvega.

There are (at least) two possible explanations for why there seem to be no such reports. The first explanation is that there is no such state of shock. I find this rather implausible, however, given what’s at stake, and given the similarities with personal death. The second explanation is that (almost?) no one is really convinced that civilization (or even mankind) is going to end soon. People do indeed say that they believe that civilization will collapse or that mankind is going extinct, and they may be quite confident in this belief, but they aren’t nearly as certain about this belief as they are about their own eventual deaths. Saṃvega requires certainty, and lacking such certainty, a similar kind of existential shock about civilizational collapse or human extinction just cannot occur.

This seems to me the most plausible explanation. It has the implication that (almost?) no one genuinely and completely believes in the collapse narrative. However, because believers in collapse aren’t really fully convinced, they need to continuously convince themselves, which makes the collapse attitude part of their self-identity. Because of that, they built up defenses against perceived attacks against their worldview (i.e. collapse), making it harder (rather than easier) to argue with them. This may seem counter-intuitive, but lack of certainty about something can make people behave as if they are more certain about that “thing”. As already mentioned above, collapse has similarities with religion – this is one of those similarities. It is, then, no coincidence that doomists are among the fiercest fanatics one can encounter in debates about climate change and its effects. (On worldview defense, see also The Stories We Believe in.)

some concluding remarks

Of the five attitudes towards, or narratives of climate change two have similarities with religious fanaticism. Those two are denial and collapse or “denialism” and “doomism”. The first of these has long been fed by fossil fuel financed propaganda and the right-wing press (i.e. most of the mainstream press), but is now becoming a fringe attitude. The second, collapse or “doomism”, is growing fast, however. The two aren’t similar just in the fanaticism of their adherents, however, but also in their harmlessness to the status quo, and therefore, their harmfulness to this planet and its inhabitants. As Michael Mann has observed, both denialism and doomism promote inaction – the first because action is unnecessary, the second because it fatalistically assumes that climate action is pointless.

Even if collapse is inevitable (because the rich and powerful rather see the world burn than share their wealth, for example), climate action is not pointless, however. We may not be able to reduce CO₂ emissions sufficiently to avoid increasing natural disasters and other (direct and indirect) effects of climate change to a level that causes global societal collapse. But there is a future after collapse, and what we do matters a great deal to that future. We can heat up the planet so much that it leaves room only for a few hundred million (or less) people struggling for their survival in an unimaginably hostile environment. (See Stages of the Anthropocene.) Or we can limit global warming to a level that gives several billions of people a decent change to survive in significantly less hellish conditions. (And surely, the interests of other species should also be taken into account.)

The fatalistic “doomism” of the collapse attitude/narrative is a threat indeed, but unfortunately so are many of the other attitudes. Given all the evidence, concern is right. The naive complacency of confidence can only lead to disaster. We cannot avoid utter disaster without making very major changes. (See The Lesser Dystopia.) And consequently, to anyone who profits from the status quo (i.e. anyone who’s wealth, power, and/or status depends on the way things are now) concern is a threat – the truth that systemic change is necessary is a threat. It is for this reason that those in power promote attitudes that are harmless to them: confidence and especially the meek and ignorant “they will fix it” version thereof, or the equally harmless collapse, alternatively.

Concern is the right attitude, however. Collapse can in principle still be avoided. It won’t be avoided, because the elites care more about their profits, wealth, status, and power, than about the future of our children (and their children, and countless animals). Anger is the right emotional response to climate change; not despair or fatalism. Despair might be appropriate when facing a terminal disease, but Earth is not dying of a disease; Earth is being murdered. The murderers are trying to bury that fact; to bury their own involvement. The murderers are obstructing action and promoting despair. Again, anger is the right response. If we want Earth to remain somewhat inhabitable, we have to fight both despair and the complacent hope that they will fix it (i.e. both confidence and collapse). Despair is our enemy. Hope is our enemy. Anger is our only ally. And we are not nearly angry enough.

If you found this article and/or other articles in this blog useful or valuable, please consider making a small financial contribution to support this blog, 𝐹=𝑚𝑎, and its author. You can find 𝐹=𝑚𝑎’s Patreon page here.

Notes

- Leslie Sklair (2017). “Sleepwalking though the Anthropocene”, The British Journal of Sociology 68.4: 775-784.

- Elisabeth Kübler-Ross (1969). On Death and Dying (Routledge).

- On Kübler-Ross’s theory in the context of attitudes to climate change, see also: Fictionalism – or: Vaihinger, Scheffler, and Kübler-Ross at the End of the World.

- Gina Gopp (1998). “A review of Current Theories of Death and Dying”, Journal of Advanced Nursing 28.2: 382-390. Gopp refers to: R. Buckman (1993), “Communication in Palliative Care: A Practical Guide”, Oxford Textbook of Palliative Medicine, 1993 edition (Oxford Medical Publications). I have not been able to find this source, however, and the paper by Buckman with title mentioned by Gopp that I did find did not include the theory she attributes to him.

- See Enemies of Our Children.

- See, for example: Rasmus Benestad et al. (2016), “Learning from Mistakes in Climate Research”, Theoretical and Applied Climatology 126.3-4: 699-703.

- I discussed a few of these models in On the Fragility of Civilization.

- Jem Bendell (2018). Deep Adaptation: A Map for Navigating Climate Tragedy, IFLAS Occasional Paper 2.

- David Spratt & Ian Dunlop (2019). Existential Climate-Related Security Risk: a Scenario Approach (Breakthrough).

- Amitav Ghosh (2016). The Great Derangement: Climate Change and the Unthinkable (Penguin).

- Ailise Bulfin (2017). “Popular Culture and the ‘New Human Condition’: Catastrophe Narratives and Climate Change”, Global and Planetary Change 156: 140-146.

- Idem, p. 142.

- I have written about hegemony and the “culture industry” on numerous occasions in this blog. For a short introduction, see chapter 3 of: Lajos Brons (2017), The Hegemony of Psychopathy (Santa Barbara: Brainstorm).

- Bulfin (2017), “Popular Culture and the ‘New Human Condition’”, p. 144.

- A. Leiserowitz et al. (2017). Climate change in the American mind: May 2017. (New Haven: Yale Program on Climate Change Communication).

- M.J. Randle & Eckersley, R. (2015). “Public Perceptions of Future Threats to Humanity and Different Societal Responses: a Cross-National Study”, Futures 72: 4-16.cc.

- S. Romi Mukherjee (2016). “Para-religions of Climate Change: Humanity, Eco-nihilism, Apocalypse”, in: T. Bristow & T Ford (eds.), A Cultural History of Climate Change (London: Routledge), pp. 192-210.

- Robert Jay Lifton (2017). The Climate Swerve: Reflections on Mind, Hope, and Survival (New York: The New Press).

- James Baillie (2019), “The Recognition of Nothingness”, Philosophical Studies (published online in August 2019). See also his earlier (2013) “The Expectation of Nothingness”, Philosophical Studies 166.S: S185-S203. And: Lajos Brons (2016), “Facing Death from a Safe Distance: Saṃvega and Moral Psychology”, Journal of Buddhist Ethics 23: 83-128.

- Baillie (2013), “The Expectation of Nothingness”, p. S189.

- Yair Dor-Ziderman, A. Lutz, & A. Goldstein (forthcoming). “Prediction-based Neural Mechanisms for Shielding the Self from Existential Threat”, NeuroImage.

- Brons (2016), “Facing Death from a Safe Distance”.

- Furthermore, as will become clear towards the end of this section, they do not even need to play such a role.

- Samuel Scheffler (2013). Death and the Afterlife (Oxford: Oxford University Press), pages 54 and 60, respectively.

- Idem, p. 44.

- Idem, p. 72.

- And he more or less acknowledges this in a footnote on page 49.

- Ernest Becker (1973). The Denial of Death (New York: Simon & Schuster).

- Sheldon Solomon, Jeff Greenberg, & Tom Pyszczynski (2015). The Worm at the Core: on the Role of Death in Life (New York: Random House), p. 211.

- Jeff Greenberg & Jamie Arndt (2012). “Terror Management Theory.” In: P.A.M. van Lange, A.W. Kruglanski, & E.T. Higgins (Eds.), Handbook of Theories of Social Psychology, Volume one (London: Sage): 398-415, p. 403.

- Much of the last three paragraphs was copied from Fictionalism – or: Vaihinger, Scheffler, and Kübler-Ross at the End of the World.

- Brons (2016), “Facing Death from a Safe Distance”.