(This is part 7 in the No Time for Utopia series.)

The main guiding principle of this series is a rejection of “ideal theory”, that is, of idealizations and unwarranted abstractions from the real world. Nevertheless, by viewing the climate crisis in relative isolation and by mostly ignoring how it might interact with various other developments, I have effectively abstracted that issue from the real world. Unfortunately, this is not easily remedied, and any attempt at a broader view will be largely speculative. It can only be speculative, because even a slightly broader view is well beyond the level of complexity that the sciences can (comfortably) handle. What this means is that we cannot predict the future, but we already knew that, of course. However, it doesn’t mean that we’re groping in the dark either. Some things are foreseeable, especially for the near future.

In this seventh chapter in the No Time for Utopia series I want to (briefly) discuss a few important technological, economic, cultural, and other developments and how they are likely to interact with the climate crisis in shaping the coming decade or decades. Most of these topics I have addressed before in this blog, but I haven’t really put the pieces of the puzzle together yet, so that’s what I’ll focus on here. But before doing that it may be useful to very briefly summarize the previous six chapters in this series. You may not have read (all of) them, or you may have forgotten them, but many of the findings in these previous chapters play key roles in the following.

summary of previous chapters

No Time for Utopia started this series by explaining its general approach: a rejection of “ideal theory”, which is characterized by abstraction, idealized agents, an aim for ideal solutions or answers, and a focus on end states rather than how to get their. All of these are harmful in the context of climate change – we must first grasp the full complexity of the situation we are in if we want to have any chance of getting out of it. Simplified abstractions and Utopian dreams may have their uses, but we’re running out of time.

The second chapter, On the Fragility of Civilization, argued that if we don’t get off the current path soon, we’re heading for global societal collapse. Contrary to typical “doomist” predictions no further catastrophic climate change is needed for that. What is projected for the coming decades – and what is already more or less locked-in as a consequence of CO₂ released in the past decades – is enough to increase levels of natural disaster frequency and intensity (i.e. droughts, floods, deadly heatwaves, and so forth) well beyond what many societies can cope with. The result will be waves of refugees and a gradual breakdown of the international trade system, which will set of a cascade of collapse. A simple simulation model suggests that global societal collapse is likely to occur some time between 2040 and 2060. The theoretical model underlying those simulations is further elaborated in a working paper also published in this blog (A Theory of Disaster-Driven Societal Collapse and How to Prevent it) and was also discussed in Michael Mann vs. the “Doomists”. (An earlier blog post, Stages of the Anthropocene looked further into the future – sketching a rather pessimistic picture of Earth in the 40th century. This post also discussed the Shared Socioeconomic Pathways (SSPs), scenarios of our socio-economic future like the one I’m sketching below, which play an important role in recent climate modeling.)

The Lesser Dystopia discussed what is necessary to avoid global societal collapse without making unrealistic assumptions about energy and without depending on technologies that are still science fiction (and that may very well remain science fiction). It turns out that our dependency on fossil fuels is so enormous that massive changes are necessary. Alternative energy cannot possibly satisfy current demand and carbon capture is “magical thinking”, and consequently, energy consumption needs to be reduced to less than a quarter of what it is now. Furthermore, agriculture needs to be overhauled completely, many other industries will have to shut down, and capitalism will have to be abolished. And those are just a few of the changes necessary. This doesn’t just illustrate what must be done, but also what is at stake. For everyone and everything invested in the status quo, too much is at stake. And because of that, the enemies of the Lesser Dystopia – that is, the Enemies of Our Children – are extremely widespread and extremely powerful. This is the topic of the fourth episode in this series. The enemy is everywhere and the enemy is nearly omnipotent. At the center of that enemy – that is, at the center of the web of money, power, and death – we find the unholy alliance of the rich, the fossil fuel industry, the financial (FIRE) industry, mainstream economics, and the state.

The next two chapters discussed two closely related aspects of the fight against these enemies. The Ethics of Climate Insurgency asked and answered the question whether it is morally justified to to use violent means to try to change course from our current path to climate hell towards something approaching the Lesser Dystopia. The answer turned out to be “No” for one simple reason: there is – in the current situation – no chance of success for a climate insurgency, and consequently such an insurgency would only cause more rather than less suffering, without getting us any closer to our goal. The next chapter, The Possibility of a Revolution further looked into what is needed for a climate insurgency or revolution to succeed. Key requirements are organizational strength and the ability to establish control over the armed forces. Obviously, climate activists don’t satisfy these (and other) criteria. It seems that the only institution that does is the military itself, but those are among the biggest polluters on the planet and have thus far only defended hegemonic interests. (This episode also pointed out that a successful revolution is useless if one fails to hold on to power, but that may be less difficult than gaining it. Assuming that the new revolutionary government controls the media and is able to use that control effectively, I’m sure that a couple of show trials against oil executives, conservative politicians, and other climate criminals followed by public execution will create massive support for the new regime.)

So this is where we are now: on the path to hell, with no way to get off. However, there may be splits in the road ahead of us. The situation may change, and perhaps, some changes can be exploited to force a change of course. Perhaps, the chances of insurgency of revolution improve. Or perhaps, other options become available. Or perhaps not. In any case, it would be useful to have a better understanding of what is likely to be ahead of us.

developments and projections

This section (and its three sub-sections) will briefly introduce some of the key expectations and developments that matter for the coming decades. The next section (and its sub-sections) will take a somewhat more narrative approach in an attempt to put these various puzzle peaces together and thereby sketch a picture of our most likely future. The first two sub-sections of this section focus on direct effects of global warming and other (political, cultural, economic, technological, etcetera) developments, respectively. The third discusses “black swans”.

effects of global warming

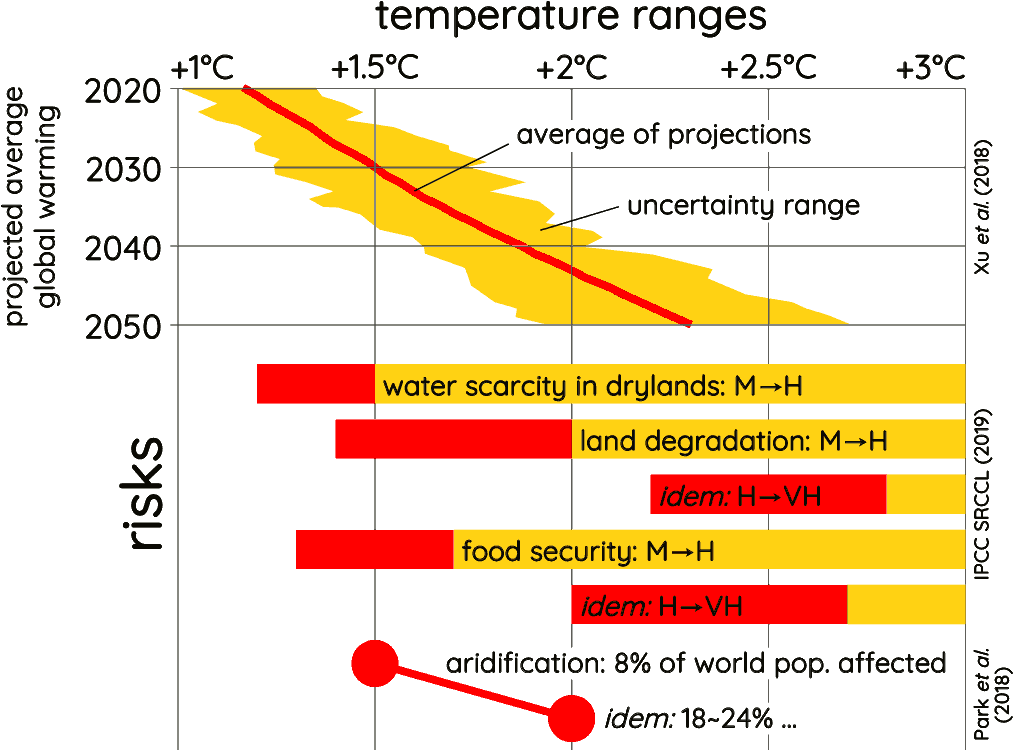

Because the focus is on the short term, effects of climate change that take many decades or even centuries to realize are mostly irrelevant here. Sea level rise is an obvious example, although it is quite likely that sea level rise will already cause serious problems for some island nations as well as for (tens of) millions of people in Bangladesh in the coming decades. What we need to know is how much warming to expect in the next couple of decades, and what this warming is likely to do right then (rather than much later). The following diagram summarizes some of this information.

The top of the diagram shows the most recent and most plausible projection of temperature increase (relative to the 1950 baseline) I’m aware of.1 Hence, in 2020 we’ll be at approximately 1.1 or 1.2°C of average global warming and by the end of that decade we’ll be at 1.5°C. Note that there are considerable margins of uncertainty, and that this is the global average – land warms up more than oceans, the poles more than tropical areas, and there are considerable regional differences in addition to that. Because there is a time lag between the increase of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere and their warming effects, much of this warming is already locked in. That is, the warming projected until 2030 or a bit later is already unavoidable, but further warming after 2040 or so can – in principle – still be avoided if we would almost completely stop releasing greenhouse gases very soon.

The five horizontal bars in the middle, labeled “risks” on the left summarize five changes in risk level mentioned in the IPCC report Climate Change and Land released earlier this year. The red part of a bar is where a change of risk level is expected to take place. Thus, between 1.2 and 1.5°C the risk of water scarcity in dryland areas (top bar) will increase from “moderate” (M) to “high” (H). And between 2 and 2.7°C risks associated with food security (bottom bar) will increase from “high” (H) to “very high”. Below these bars, two big red dots connected with a line marks another important finding, namely that 1.5°C of warming will result in aridification (severe drying) affecting approximately 8% of the world population, while 2°C will result in aridification that affects between 18% and 24% of the global population.2

A similar comparison between scenarios of 1.5 and 2°C of average warming is made in the IPCC special report Global Warming of 1.5°C (GW1.5) published a year ago, but for many more variables. Here’s a very short summary: Two to three times as many species of plants, insects, and vertebrate animals will lose more than half of their geographical area. Many of these will go extinct. Approximately 13% of land area will experience ecosystem collapse (compared to 50% less at 1.5°C). Coral reefs will go virtually extinct and ocean acidification will (even) more severely threaten mollusks (shellfish, etc.), plankton, algae, and many species of fish. The loss of average annual catch for marine fisheries will be twice as high at 2°C as at 1.5°C. There will be a significantly greater reduction in crop yields for major food crops at 2 than at 1.5°C, especially in economically less developed regions. Several hundreds of millions of people more will be exposed to climate-related risks such as natural disasters, food- and water-shortage and insecurity, and poverty.

Combining the various parts of the graph (as well as the predictions of the GW1.5 report), we can see that in the 2020s water scarcity will be an even bigger problem than it is already, and that towards the end of that period, land degradation and food security will start to become major issues as well. This continues throughout the 2030s, and by the middle of the 2040s at least a quarter of the global population will suffer from shortages of food and water.

In addition to all of that there will be a continuing, gradual (but probably exponential rather than linear) increase of natural disasters and extreme weather such as storms (including hurricanes and typhoons), floods, deadly heatwaves, and so forth. This and last year, hurricanes devastated the Caribbean, for example, and this will only get worse. Thus far, there appears to be much confidence in the possibility of rebuilding, but that confidence will probably evaporate when rebuilt areas are destroyed again one or two years later. That is not far ahead in the future – much of the Caribbean may be effectively uninhabitable due to recurring super-hurricanes in less than 10 years from now. And other areas will only be able to support a fraction of their current population due to recurring floods (Bangladesh, Pakistan, …) or droughts (the Middle East, parts of Central America, …).

other key developments

There is, of course, no shortage of other trends and developments that could be discussed here, but I will limit myself to short descriptions of the three most important ones: the rise of artificial intelligence (AI), economic stagnation and crises, and the rise of authoritarianism and (neo-) fascism. All three have been discussed before in this blog, which is the main reason why I’ll be brief here. (See especially: Crisis and Inertia (4) – Economic, Political, and Cultural Crises.)

Automation has always simultaneously destroyed and created jobs. The jobs destroyed were mainly blue-collar jobs, while the jobs created were white-collar jobs. Because much used to be invested in education and general levels of education rose, these white-collar jobs were filled easily, leading to a growing middle class. But things are different now. Of course, almost everyone realizes that there won’t be many humans driving trucks and trains in a decade from now, but Artificial intelligence (AI) doesn’t just threaten blue-collar jobs anymore (many of which have been moved to low-income countries, by the way) – it has become a serious threat to white-collar jobs. And there is no plausible prospect that AI will create sufficient new (kinds of) jobs to make up for the losses. Already, AI pharmacists are better than human pharmacists – they are faster, more accurate, make less errors, and are much more capable at judging the interaction between multiple prescriptions. AI “lawyers” are better than human lawyers at pretty much everything except pleading in court. And so forth. In other words, the kinds of jobs that are under threat now include relatively high status (and high income) jobs that require higher education (and slightly less high-status administrative jobs etcetera will disappear even sooner).

AI is developing fast. Within the next ten years very many jobs will disappear – AI drivers will become the norm in the transport sector, but AI will also take over more and more office jobs and other white-collar jobs. Some new jobs will be created, but there won’t be enough, and they won’t be comparable to the high-status jobs that AI will make obsolete. We’re rapidly approaching a stage where almost any job – new or old, and including the development of AI itself – can be done more efficiently by AI. The consequence is unemployment and falling wages. At some point, this will make hiring humans cheaper again, but only for low-paid jobs. The owners of AI systems will reek in the money, while much of the rest of humanity becomes economically useless and disposable. However, because this will also drastically reduce consumer spending (because unemployed “consumers” don’t have much to spend), it will also negatively affect economic growth. It might be possible to avoid the latter by means of a very generous system of universal basic income, however, but it is rather doubtful that the elite (i.e. the people owning the AI) will be willing to share enough of their wealth to make that possible. Elites rarely give up even a small part of their wealth and power voluntarily.

The decimation of the middle class by the rise of AI is not the only threat to economic growth and stability and not even the biggest one – that dubious honor goes to debt, private debt to be more precise. I have written about this before in Rent, Debt, and Power, so I’ll be very brief here. Debt results in a transfer of wealth from the productive parts of an economy to the financial (FIRE) sector. Private debts are especially problematic. If those reach a level of roughly 150% of GDP, then households and companies have too little money left after paying what they owe to the financial sector, consumption starts to decline (sometimes sharply), and the economy collapses.3 This is what happened in the “Great Recession” of 2008 and virtually all economic crises before that.

Historically, economies were revived by means of debt cancellation, bankruptcies, and/or other tools that produced a more or less clean slate, but in the Great Recession this wasn’t allowed – or insufficiently, at least – so debt levels remained very high. The reason for this is that as long as debt level remains high, the financial sector can continue to suck money out of the real economy, and unfortunately, the financial sector pulls the strings. (See Rent, Debt, and Power and Enemies of Our Children.) Consequently, consumption cannot sufficiently recover and economic growth remains low, turning a country into what Steve Keen calls a “debt zombie”.4 Many of the world’s largest economies are debt zombies already, which has lead to worldwide economic stagnation. (Only the financial sector escapes that stagnation, of course, as they are allowed to continue their parasitism. This particular parasite is slowly killing the host, however.5)

What’s even more reason for concern, however, is that there are many countries, including some of the world’s largest economies, that have unsustainably high levels of private debt. Some of those are well over 150% and only manage to hang on due to government intervention. (China is by far the biggest economy in that group.) This cannot continue forever, however, because government coffers become empty sooner or later. Consequently, another major financial crisis is looming on the horizon, and there is a good chance that it this one is going to be worse than the Great Recession. This time, governments won’t have the money to bail out the banks (who caused the crises anyway) because they are too indebted (to the banks) already. So parts of the financial sector are going down, and it is very hard to predict what they’ll be taking with them. Functioning governments that prioritize the real economy and their citizens could probably minimize the economic effects of a failure of the financial system (because that is largely parasitic anyway), but because governments are so close to the financial sector and have effectively been under the latter’s control for decades,6 it is very unlikely that they’ll have the right priorities – more likely government intervention will just try to protect financial interests and thereby make the effects of the crisis even worse for households and industry.

Given the state of the Chinese, American, Japanese, and German economies,7 I expect a major economic crisis within a few years from now. It may start very soon; it may be postponed for a few years; but there can be no doubt that there is going to be a major economic contraction in the first half of the 2020s. And after that, there will be a different economic landscape. How disastrous the coming crisis is going to be, and how much chances there are of recovery after it, is hard to predict. That – again – depends very much on whether governments prioritize the financial sector or the real economy. Given that the financial sector effectively owns governments (and controls them ideologically as well8), I see very little reason for optimism.

The third “other” key development that must be taken into account to see where we’re going is the worldwide rise of right-wing authoritarianism, nationalism, and/or fascism. There are interesting similarities and differences between this phenomenon and the wave of fascism that lead to the second World War 80 years ago. Unemployment, economic decline, and financial/economic insecurity fed rising fascism in the 1930s, as they do now. And consequently, the aforementioned two developments – AI and economic crisis – are very likely to reinforce this trend. On the other hand, 1930s fascism included an economic program that was focused on industry and national economic growth, while the current wave of right-wing authoritarianism tends to go hand in hand with varieties of neo-liberal capitalism. For that reason, it is more appropriate to speak of “neo-fascism” in reference to the current trend than to call if “fascism”. Terminological issues aside, this is a very important difference, because it means that neo-fascism is no threat to the economic and political elite. In the contrary, it can be a very useful tool to consolidate and protect their power and deflect threats. As long as the people are occupied with illusions of national grandeur and with blaming scapegoats – such as foreigners and refugees – for any perceived decline of, or threats to that grandeur, they do not threaten the rich and powerful. It is no wonder then, that the elite-owned and elite-controlled mainstream press has been fanning the flames of right-wing sentiment. And it is unlikely that this will change soon.

But even if economic and political elites wouldn’t support the rise of neo-fascism because it is so useful to them, it would probably rise by itself. Or not “by itself” exactly, but due to other developments. Again, economic crisis and stagnation cause (through unemployment and falling wages) financial insecurity, which results in political radicalization and scapegoating. Among political ideologies, (neo-)fascism is the primary beneficiary of economic decline. Furthermore, the traditional support base of democracy – and the main bulwark against fascism – has been the middle class, and AI is threatening the middle class. It is quite likely that within a decade from now very many middle class jobs no longer exist because AI can do them cheaper and more efficiently. Under the influence of right-wing propaganda, a significant part of the army of newly unemployed or under-employed former members of the middle class are likely to forget their former democratic or even liberal ideals and join some authoritarian and nationalistic cult.

There is, moreover, another factor that pushes us towards neo-fascism: climate change itself. Recent research has shown that natural disasters and (other) environmental changes that threaten (economic) security change a society’s norms and preferences – they become more intolerant of deviations, demand harsher punishment for violations, less open, more prejudiced (i.e. racist etc.), more authoritarian, and more hostile towards minorities.9 Or to put this in one short sentence: climate change breeds (neo-)fascism.

In addition to the role of economic decline and insecurity there is an other possible – perhaps, even probable – parallel between the 1930s and the current situation, although it hasn’t materialized yet. 1930s fascism was fairly successful in addressing the unemployment issue from which it (partly) arose – raising an army and sending it to war is a rather efficient way to get rid of your surplus labor supply. Although this may seem unthinkable right now, it would not be surprising if we’re going down this same route again. And to a large extent, it is AI that makes the unthinkable possible. When AI becomes more efficient and cheaper at almost everything, the vast majority of humans become useless, disposable, and expendable. There will be a vast army of un- and underemployed, more or less worthless humans available to repress dissent (including climate activism!), guard borders and fortified palaces, and to fight wars against other armies of disposables. This will solve several problems at once – at least from an elite perspective. It channels social stress and unrest into “harmless” hostility and violence towards other victims (i.e. refugees, foreigners, etc.), while allowing the guilty to remain in the shade. It removes climate action as a threat to the status quo (from which they profit). It puts the human surplus population to “good” use, and reduces it at the same time. And it keeps the elite’s fortresses safe (at least for a while) from the tidal wave of climate refugees. Tricking the disposables to become foot soldiers and border/palace guards is so advantageous – and so easy (!) – to the elite (especially considering their control over the mass media) that I have little doubt that this will happen (unless unexpected events prevent it; see next section). The question is just how long it will take.

What these last two paragraphs illustrate is that the climate crisis, the slow suicide of neo-liberal capitalism, the decimation of the middle class by AI, and the rise of neo-fascism are not isolated problems, but are all closely related and are reinforcing each other. And it’s unlikely that this convergence and amalgamation of socio-economic and technological developments will bring a solution to the climate crisis any closer. In the contrary, neo-fascism has an even poorer track record when it comes to environmental issues than neo-liberalism.

black swans

In his book The Black Swan, Nassim Taleb points out that highly improbable, but extreme events have large and unpredictable effects.10 The occurrence of such “black swans” makes predicting the future rather difficult. Many of the “doomist” scenarios of near term human extinction and other catastrophes that you can find on the internet are based on the assumption that a certain kind of black swan or “fat tail” event will happen, but given their improbability (by definition), such an assumption makes the scenario itself highly improbable. Nevertheless, black swans must be taken into account. Unfortunately, the black swans that no one saw coming and that no one even knew that existed (like Donald Rumsfeld famous “unknown unknowns”) are often the ones that have the biggest impact, and those – because we don’t know them – cannot be taken into account. So, we’re limited here to the blacks swans that we know to exist, but even that list is much longer than what I have space (and patience) for in this article.

For example, a solar storm disrupting electric power networks and frying a substantial percentage of electric tools and appliances worldwide may seem like some kind of remote or exotic possibility, but recent research suggests that something like this may happen about once every century.11 (The last ones were in 1859 and 1921.) If that’s correct, then there appears to be a roughly 10% chance of a solar storm in the 2020s, for example. Would something like that happen in the near future, then the effects would be devastating. The world would be without electric power. In some places it might be restored quickly, but it may take weeks, months, or even longer to restore power in many other places. And even if power is restored, many of the electr(on)ic tools and appliances (including satellites) that we rely on would no longer work. Without electricity almost everything would break down. Most importantly, food and water would get scarce soon, leading to riots, which would be hard to contain as security forces (and everything else) rely on electricity just as much. In other words, while a solar storm may not seem as apocalyptic as a massive meteor impact, for example, and would certainly not cause as many direct deaths, the people surviving the mayhem will be living in a very different world.

There’s also a chance of nuclear war, of course, especially if right-wing authoritarianism, nationalism, and militarism keep rising, and unfortunately there is good reason to believe they will (see above). It’s hard so give any credible estimate of how likely nuclear conflict is, and what the scale of that conflict would be. An escalation of the conflict between India and Pakistan is generally considered to be the most probable nuclear war, but there surely are many other plausible scenarios imaginable. Even a fairly small, regional nuclear conflict would have disastrous effects, however. Soot in the atmosphere resulting from burning cities would lead to massive droughts and a small drop in average global temperature, killing up to 2 billion people worldwide.12 Of course, the effects of a full-scale nuclear war between the nuclear superpowers would be far more devastating, resulting in an ice age for at least a few decades and killing something like 99% of humans, but full-scale nuclear war is also much more unlikely than a small-scale regional conflict, and it is important to realize that such a small-scale regional conflict would already be so devastating that little would remain the same.

In addition to catastrophes like solar storms and nuclear war, there also are more positive black swans. There may be a technological breakthrough, for example, that completely changes everything. This too, is quite unpredictable, of course. And some of the most important technological advances are hiding in plain sight. The washing machine, for example, made it possible for (many more) women to join the labor force, for example, which was one of the main sources of economic growth in the second half of the 20th century, but which also led to major cultural and social changes in industrialized countries. In hindsight, this is kind of obvious, but I doubt that anyone would have predicted it a century ago. It may be that some big technological development – in nuclear fusion or carbon capture, for example – leads to revolutionary changes, but it is also quite possible that something much more pedestrian – something like the washing machine – leads to social and cultural changes that are so big, that any attempt to predict the future is doomed to fail.

Let’s say that we are trying to predict in broad outlines what Earth is going to be like in 2050. And let’s assume that we have an accurate assessment of all the relevant trends and developments. Then, given the occurrence of black swans, what’s the chance that our prediction is going to be correct? The problem with black swans, of course, is that we don’t know most of them, and that even for the ones we do know, we have no precise or reliable data about their probability. But let’s just play with numbers a bit. If the once-per-century estimate for solar super-storms is correct, that gives us a probability of at least 30% of one occurring before 2050. (Given that the last one was in 1921 and the one before that in 1859, this may be a low estimate, however.) What’s the chance of at least one regional nuclear conflict occurring between now and 2050? I really have no clue how to estimate this, but let’s say it’s a similar percentage. And let’s assume the same probability of a revolutionary technological breakthrough. Then, taking into account only these three known possible black swans, the chance of none of them occurring is (1–30%)3=34%. Again, I’m just playing with numbers here, but none of these numbers seem particularly implausible and there obviously are other black swans that could disrupt things as well. What this means, is that even if we could come up with a perfect prediction, the chance that that prediction is going to be realized is considerably smaller than the chance that it will be invalidated by some big, apparently random event.

This doesn’t mean that predicting the future is a waste of time, however, for two reasons. Firstly, predictions clarify the path one is on, and where it is leading. And secondly, some predictions are more robust than other. Short-term predictions are obviously much less sensitive to black swans, but long-term predictions can also be if they are about systems that are less sensitive. Climate predictions and other Earth system predictions, are relatively robust, for example, while social, cultural, and economic predictions, on the other hand, are notoriously difficult. (This is one of the reasons, by the way, why the Shared Socioeconomic Pathways (SSPs) are so utterly absurd. Those scenarios are attempts to look decades ahead, but do so by assuming that nothing ever happens. Even if we ignore other fatal flaws in the approach itself (such as the nonsensical economic model at its base), given that we know one thing for sure about socio-economic development – namely that everything changes – the one thing we can know about the SSPs is that they cannot possibly come true.13)

the near future

With the implicit caveat of the last paragraphs in mind, let’s see whether we can get a clearer picture of the near future if we put some of the pieces of the puzzle together.

If you look back at the figure showing projected average global warming and temperature ranges of changing risks above, then you can see the expected time frame for several key environmental changes. I’ll summarize these here.

- 2020-2030: water scarcity becomes a much more severe problem in dryer parts of the planet (such as the Middle East, parts of South Asia, and parts of Central America), resulting in increasing stress, violent conflict, and migration (i.e. refugees).

- 2025-2035: food security becomes a major risk factor in many parts of the world. Hunger and food riots become common everywhere except in some (or perhaps, most) of the rich, industrialized nations. (Resulting, again, in increases of violent conflict and refugee flows.)

- 2030-2045: the percentage of people affect by severe drought triples. Water scarcity and food security become even bigger problems. Deadly heatwaves become common in regions closer to the equator (but also elsewhere). And so forth.

- And during all of this period, there is a steady – and probably exponential rather than linear – increase in natural disasters such as storms (including hurricanes and typhoons), extreme rain or snow, deadly heatwaves (in summer) and cold spells (in winter), floods, droughts, and so forth.

2025

The first half of the 2020s will almost certainly be very similar to the world we live in know. Trends that have characterized the past years continue, and fundamental shifts and changes will take a bit more time to materialize. The one major stone in the pond – probably, causing shock-waves rather than ripples – is a financial crisis. Like the Great Recession of 2008, it starts in the financial sector, but because governments are too indebted already to bail out the banks again, this time it results in some big bankruptcies, and the effects spread out through the rest of the economy.

Unemployment and financial insecurity resulting from the crisis (further) deteriorate people’s faith in the socio-economic status quo. Neoliberal capitalism and allied ideologies (such as centrist liberalism) lose (even more) support, while more radical ideologies grow. Mainly due to the mainstream press’s continuing marginalization of the left and normalization (if not celebration) of the (far) right, right-wing extremist ideologies profit from this most.

Anger about the climate crisis also continues to grow – especially among young people – as more and more people become aware of the seriousness of the issue and of the refusal of economic and political elites to seriously address it. The elites respond to the growing anger by reinforcing their propaganda and disinformation war, leading to increasing polarization between informed and concerned citizens and those who are fooled into ignorant complacency (including the far right).

Suppression of climate activism is further intensified, and increasingly also affects climate science and attempts to inform people about the climate crisis. Thousands of so-called “climate terrorists” are jailed (many of them on the basis of fake or trumped-up charges) or even assassinated. With tacit support from the government and mainstream press, right-wing extremists violently attack climate activists and climate scientists. Propaganda and disinformation further weakens the movement, and suppression will scare many potential climate activists into submission. The small part of the climate movement that doesn’t submit radicalizes, but they are demonized by the press and their actions only give governments an excuse for crackdowns and further suppression.

Some largely symbolic measures to counter climate change are implemented, however, but they don’t have any significant effect. Still, they are sufficient to trick many into believing that the problem is being addressed. Michael Mann continues to warn that people predicting catastrophe are more dangerous than climate changes deniers and becomes a tool in the propaganda war against climate activism. Efforts to reach international agreements about climate change (and its effects) fail due to growing frictions between countries (partially due to rising nationalism; partially due to the uneven spread of the effects of climate change).

By 2025, some Caribbean nations only exist on paper. People have given up on rebuilding and just try to leave. In the following decade, the same becomes true for many other areas that just keep being pounded by super-storms (and/or other disasters) year after year. (New Orleans won’t be rebuilt again and again.) Storms and floods in Bangladesh make between ten and twenty million people homeless. Many of them try to flee to India, which responds by fortifying its borders and shooting refugees who try to pass them. Parts of Central America, Africa, and the Middle East become too dry to support their populations. Millions of people try to flee to Europe and the US, but like India, those respond by fortifying their borders and herding refugees into concentration camps. Right-wing anti-refugee hysteria is fanned by the press, leading to widespread support for these policies.

2030

In the second half of the 2020s the development of AI makes more and more white-collar jobs obsolete. The frustration and uncertainty of the growing army of the unemployed is redirected through propaganda at refugees and deviants (such as anti-fascists, climate activists, sexual and other minorities, and pretty much everyone else who doesn’t fall in line). Neo-fascism becomes the dominant political ideology in all industrialized nations. Border defense, militarized police, and incarceration of immigrants, refugees, and dissidents become the main employers of the members of the former middle class who have lost their jobs to AI.

Refugee flows from tropical regions that are hardest hit by drought and other kinds of climate disaster to the temperate zones continue to grow. Many countries in the tropical regions are slowly turning into failed states and (civil) wars over scarce resources such as water are spreading. India is no longer able to keep refugees from Bangladesh out because it is itself on the verge of collapse due to drought, deadly heatwaves, and other disasters. Much the same is true for Pakistan, and the conflict between the two over Kashmir – an important source of water – escalates.

Because no serious effort was made to significantly reduce CO₂ emissions in the 2020s, average warming up to a least 2°C by 2040 or 2045 is now locked in, setting off and strengthening various feedback loops, and triggering some systemic changes (i.e. tipping points). Much of the Amazon has changed from rain-forest into savanna (and what is left will follow soon), many boreal and tropical forests have been lost to fire, and much of the permafrost is melting. Climate change has spun out off control. Efforts to counter climate change (by means of new technologies and new policies) increase, but it is too little and much to late to save us.

2035 and beyond

In the zombie movie “World War Z” there is a scene in which thousands of zombies try to break through the walls of Jerusalem. There are too many of them, and eventually they succeed. Something similar will become common in the 2030s, except that the “zombies” are refugees (and thus, people like you and me), and the walls they are trying to break are the fortified borders of neo-fascist states. (And probably, zombie movies will be used as propaganda tools to dehumanize the refugees and make it easier for the border guards to kill them.)

Like domino stones, the fortresses fall, one after the other. By 2050 (and probably much sooner) none are left. Civilization is a thing of the past. The planet is a smoking chaos. Large parts are effectively uninhabitable, and the remainder is embroiled in continuous civil war. By the end of the century, due to various feedback effects and tipping points, average warming will have reached at least 6°C. The tropics are uninhabitable and the temperate zones are shrinking fast. The oceans are mostly dead. Two billion or less people have survived the 21st century, but that’s still too many for the shrinking habitable zone and the scarce resources that are left.

For how things develop from here, see: Stages of the Anthropocene.

some objections

There are many reasons someone might have to be skeptical about the scenario sketched above. I’ll just mention three here, but it is quite possible that this section will be expanded later.

In discussions about climate change, one of the most common things I hear is something like “we won’t let it happen”, but the people who say that always mean “they” when they say “we”, because those people are not doing anything themselves – they merely expect that “they” will solve the climate crisis. But “they” – regardless of who “they” are – won’t. Climate armageddon is too profitable for the elite, and because they will be dead before things get really bad, the negative effects of climate change don’t concern them. They won’t save us – they make too much money by condemning us to hell.

Another possible objection could be that political culture is like a pendulum: it swings to the right now, but eventually it will swing back to the left. Perhaps, but it has been swinging to the right for a long time, and there are many forces pushing (or pulling) it further to the right (as if someone stacked up a bunch of magnets on one side of the pendulum). Financial insecurity and unemployment due to the slow death of neoliberal capitalism and the rise of AI will strongly support a further “swing” to the (extreme) right. Moreover, liberalism, democracy, and tolerance (i.e. the things that might pull the pendulum to the left again) always depended primarily on the middle class, but AI will wipe out most of the middle class. Hence, there is very little reason to believe that the pendulum will swing back.

Perhaps, the most common objection will be that I’m exaggerating things. But what exactly am I exaggerating? The climate effects I mention mostly come from rather conservative and cautious sources like IPCC reports. What I predict for AI in a decade is already mostly possible now. And some countries (such as the US, Turkey, Russia, and many others) are already scarily close to the neo-fascist states I’m predicting to arise in the near future. Europe and Australia already herd refugees in concentration camps, the US is already working on a border wall, Turkey is already jailing environmental scientists, climate activists are already being murdered and imprisoned, and so forth. None of the individual trends and developments I mentioned should be surprising to an open-eyed observer of the world we live in. All I did in the preceding paragraphs was to put the pieces together.

Nevertheless, it can’t be emphasized enough that the foregoing is a sketch of the path we’re on. It’s not the only possible path, and we may still be able to get off this path.14 I don’t believe we will, however, because all the money and power in the world keep us on this path. In the first episode of this series I wondered whether I was overly pessimistic. I guess I was searching for a glimmer of hope, but I have found none. If anything, writing this series had made me more pessimistic. Mankind will probably survive, but not in enviable conditions, and few of mankind’s achievements will survive the 21st century. This doesn’t mean that there is nothing we can do, however, or that everything is futile, but that is a topic for the next (and probably final) chapter.

Links to articles in this series:

No Time for Utopia – Series introduction. Against “ideal theory” and Utopianism.

On the Fragility of Civilization – Predicting global societal collapse within decades.

The Lesser Dystopia – What is necessary to avoid that collapse?

Enemies of Our Children – Who and what are preventing the necessary change of course?

The Ethics of Climate Insurgency – On violence as a means to prevent catastrophe

The Possibility of a Revolution – Can a revolution establish the Lesser Dystopia?

The 2020s and Beyond – This episode.

What to Do? – Some closing reflections on what we should and can do.

If you found this article and/or other articles in this blog useful or valuable, please consider making a small financial contribution to support this blog 𝐹=𝑚𝑎 and its author. You can find 𝐹=𝑚𝑎’s Patreon page here.

Notes

- Wangyang Xu, Veerabhadran Ramanathan, & David Victor (2018). “Global Warming Will Happen Faster than we Think”, Nature 564 (6 December 2018): 30-32.

- Chang-Eui Park et al. (2018). “Keeping Global Warming within 1.5ºC Constrains Emergence of Aridification”, Nature Climate Change 8: 70–74.

- Richard Vague (2014). The Next Economic Disaster: Why It’s Coming and How to Avoid It (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press). Steve Keen (2017). Can We Avoid Another Financial Crisis? (Cambridge: Polity).

- Steve Keen (2017). Can We Avoid Another Financial Crisis?.

- Michael Hudson (2015). Killing the Host: How Financial Parasites and Debt Bondage Destroy the Global Economy (Petrolia: Counterpunch Books).

- There is a staggering number of former financial executives holding key administrative posts in many countries, but much of the control takes less direct and more ideological forms. See Rent, Debt, and Power and: Lajos Brons (2017), The Hegemony of Psychopathy (Santa Barbara: Brainstorm).

- China and Japan have way too much private debt. The former is well beyond danger levels but is still propped up by its government. Japan is dangerously close to a crisis, but probably won’t collapse by itself. Germany is also struggling with debt and is, moreover, on the brink of a recession, from which it may not easily recover (if at all) as its economy is heavily dependent one export and worldwide austerity (enforced by the financial sector) has reduced the number of available export markets. The US is a debt zombie with very high private debt. Consumption has remained high for decades “thanks” to rising debt despite falling real wages, but debt cannot rise much more and wages aren’t increasing. Hence, the American economy is more or less stagnant, but this is not a stable situation. Frictions which China, banks pushing more debt onto already impoverished consumers, incompetent economic policy, and various other factors are slowly pushing the US over the edge and into the economic abyss as well.

- Controlling the host’s brain is a very effective strategy for a parasite. The financial sector does exactly that. See: Rent, Debt, and Power; Hudson (2015), Killing the Host; and Brons (2017), The Hegemony of Psychopathy.

- Joshua Jackson et al. (2019). “Ecological and Cultural Factors Underlying the Global Distribution of Prejudice”, PLOS One 0221953.

- Nassim Taleb (2007). The Black Swan: The Impact of the Highly Improbable (New York: Random House).

- Jonathan O’Callaghan (2019), “New Studies Warn of Cataclysmic Solar Superstorms”, Scientific American, online.

- See the section on nuclear weapons in Crisis and Inertia (3) – Technological Threats and Crises, as well as the papers referred to there. For an important recent recent contribution to the literature on the effects of nuclear war, see: Owen Toon et al. (2019), “Rapidly Expanding Nuclear Arsenals in Pakistan and India Portend Regional and Global Catastrophe”, Science Advances 5: eaay5478.

- On the SSPs, see also: Stages of the Anthropocene.

- Provided that we can take control of the press and dispose of the parasitical elites very soon. See various previous episodes in this series.