The best explanation of the psychological roots of radicalization and terrorism is given by Terror Management Theory (even if the word “terror” in that name has nothing to do with terrorism). Western governments appear to be completely ignorant of this explanation, however, and as a consequence, much of their actions promote terrorism more than counter it.

* * *

There is no uncontroversial definition of “terrorism”.1 To a large extent, calling something “terrorism” or someone a “terrorist” is a political claim intended to de-legitimatize an opponent and to express disapproval of his or her actions and goals. Nevertheless, there are typical elements that most – if not all – acts of terrorism share:2 they are violent, they have goals beyond the immediate results of the act, they are intended to create fear and/or to have other psychological effects on larger populations, and they are not committed by a state.3 The third of these typical elements is particularly noteworthy because many (and perhaps even all) kinds of terrorism are not just intended to create fear, but are also fed by fear. ISIL/ISIS/Daesh and its affiliates (in a rather loose sense of “affiliate”) are the most notable contemporary example of this kind of terrorism.

The best explanation of the psychological roots of (this kind of) terrorism is given by Terror Management Theory. The word “terror” in the name of that theory, has nothing to do with terrorism, however, and neither is the theory about how terrorism could be “managed”. Rather “terror” refers to the fear of death, and “management” to the psychological and cultural mechanisms to control that fear. Terror Management Theory was developed in the 1980s by the psychologists Jeff Greenberg, Tom Pyszczynski, and Sheldon Solomon on the basis of Ernest Becker’s writings about the “denial of death”.4 According to Becker, much of civilization (religion especially) is a defense mechanism against the fear or “terror” of death. Civilization is an “immortality project” – it allows me to become part of and to contribute to something that not just survives my biological death, but that seems to offer the promise of eternal life.5

Terror Management Theory (TMT) took many of Becker’s ideas, turned them into testable hypotheses, and then put them to the test. According to TMT, “the awareness of death gives rise to potentially debilitating terror that humans manage by perceiving themselves to be significant contributors to an ongoing cultural drama”, and “reminders of death increase devotion to one’s cultural scheme of things”.6 Hence, much of what we humans do and believe is driven by “terror management”, that is, controlling the fear of death, and “effective terror management is faith in a meaning providing cultural worldview and the belief that one is a valuable contributor to that meaningful world”.7 In other words, reminding people of their mortality – or increasing “mortality salience” – leads them to bolster both their worldviews and their beliefs that they are valuable contributors to the world according to that worldview. This idea is called the “Mortality Salience Hypothesis”, and is the most extensively tested of the TMT hypotheses. A meta-analysis covering 164 articles on 277 experiments concluded that the Mortality Salience Hypothesis “is robust and produces moderate to large effects”.8

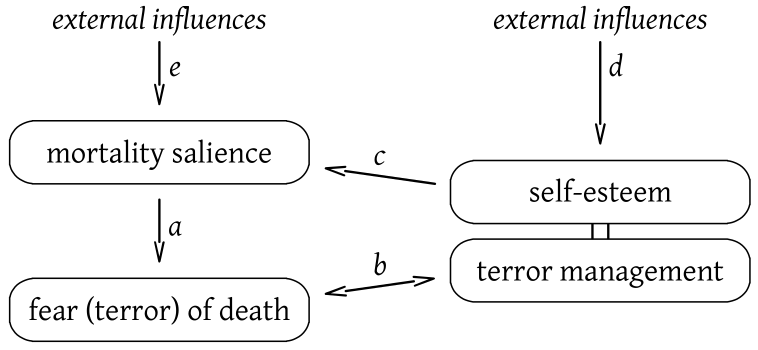

The diagram shown in figure 1 graphically summarizes the main features of TMT and will serve as a guide for further explanation in the following. In addition to the core concepts already mentioned above, the diagram shows a fourth, “self-esteem”, which is “the belief that one is a valuable contributor to [a] meaningful world” (in terms quoted above), and thus depends partially on a worldview that provides that meaning(-ful world). (It should be noted that this understanding of “self-esteem” is not significantly different from common understandings and uses of that term, although that may not be immediately obvious.)

Mortality salience is the extent to which one is consciously or subconsciously aware of death. An increase in mortality salience produces an increase in the fear/terror of death (arrow a), but this process (and that fear) can be largely unconscious. An increase in the (conscious or unconscious) fear of death must be countered (that is, brought under control or “managed”) by a reinforcement of terror management (arrow b, left to right), and this too, can happen unconsciously. Strengthened terror management decreases the fear of death (arrow b, right to left), thus restoring balance. While these relations (arrows a and b) are – more or less – causal, the relation between terror management and self-esteem, the fourth core concept, is of a somewhat different nature: terror management is self-esteem insofar as (and when) it is used to “manage” or control the fear/terror of death.

Arrows a and b represent the Mortality Salience Hypothesis, the part of TMT that has been most extensively tested and proven, but there also is empirical evidence for arrow c, which represents the relation between self-esteem and mortality salience.9 Lower self-esteem leads to more (conscious or unconscious) death-related thoughts, and thus to increased mortality salience, and higher self-esteem has the opposite effect. The remaining two arrows, d and e, are not part of TMT proper, but represent the two main outside influences on the “system”. Various events and encounters affect one’s self-esteem and mortality salience. Rather obviously, witnessing a car accident (or seeing one on TV), for example, increases mortality salience. And being the victim of discrimination reduces self-esteem, while winning a price increases it.

The most central aspect of the theory is terror management (hence its name). People manage the terror of death by strengthening their worldviews and their beliefs that they are valuable contributors to the world according to that worldview. This is called “worldview defense” (although that term is not used with the exact same meaning in all sources). Although the two aspects of worldview defense are closely related, it is useful to make a distinction between strengthening one’s (cultural, religious, political, etc.) worldview itself, and strengthening the belief that one is a valuable contributor to the world according to that worldview. The former generally takes the form of radicalization, but the effects of such radicalization depend very much on the nature of the worldview. An adherent to a worldview in which compassion is a core value will become more radically compassionate, for example.10 Strengthening the belief in one’s own value relative to that worldview (i.e. the second aspect) can also take several different forms, ranging from a mere (delusional?) strengthening of belief to actually contributing more and/or differently, and the nature of such contributions depend on the nature of the worldview, of course. Despite this variation in the forms worldview defense can take, there are common elements. It almost invariably increases cultural, religious, and/or ideological identification (and other subjectively important aspects of self-identity),11 strengthens belief in and/or consent to the doctrines of that culture/religion/ideology, and increases negativity or even hostility towards other cultures/religions/ideologies.12

Above I claimed that TMT provides the best explanation of the psychological roots of terrorism. Obviously this should not be taken to mean that TMT completely explains terrorism, or that it explains all kinds of terrorism. Such claims would be absurd. Terrorism – like almost any social phenomenon – is much too varied and much too complex to be captured in a single theory. I do want to claim, however, that TMT explains several of the most important psychological processes involved in terrorism and radicalization, and that terrorism and radicalization cannot be effectively countered, or even understood, without taking these processes into account.

In August 2016, a Dutch court sentenced MG to three years in prison on charges of terrorism. MG hadn’t done anything (yet), and there was little direct evidence that he was going to do anything illegal. Moreover, it is not entirely clear whether the evidence for his plans was gathered legally. What is most interesting about the case, however, is MG’s recorded statement (by means of a bug): “I want to fight, I want to kill, I want to be”.13 The last item on that short list is what it’s all about: wanting to be.

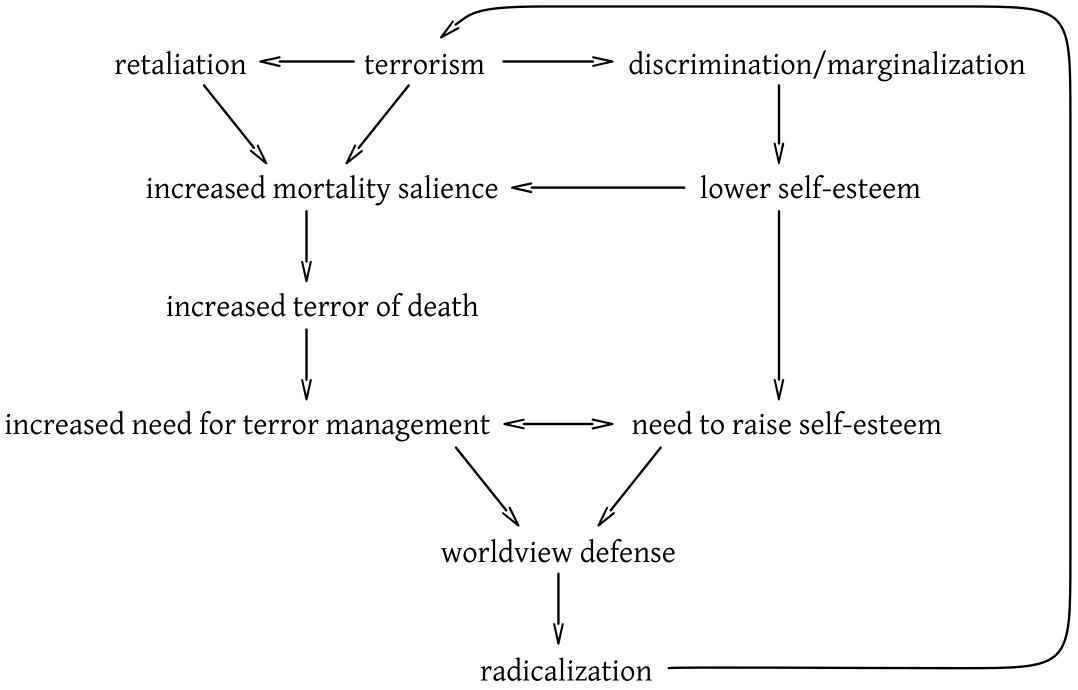

Figure 2 schematically represents the main psychological processes involved in terrorism and will function as a guide below (as figure 1 did before). Because – as the figure shows – these processes are circular (this is, in fact, as vicious as a vicious circle can get) we could start anywhere in the figure, but let’s start at the same point as before: with mortality salience.

An increase in mortality salience (i.e. awareness of death and/or unconscious reminders of death such as violence) leads to a conscious or unconscious increase in the fear or terror of death, which needs to be countered (or “managed”) by means of strengthening terror management. Towards that end, the subject engages in worldview defense. As mentioned, the form this takes depends among others on the nature of the subject’s worldview, but also on other circumstances. Worldview defense strengthens identification with an “in-group” (i.e. the social group to which the subject belongs), as well as hostility towards “out-groups” (i.e. other social groups), but if there is no clearly defined in-group identity or if there is little reason for hostility towards out-groups these effects may be weaker. Conversely, more clearly defined in-group identities are more likely to produce strengthened in-group identification, and hostility towards out-groups is more likely to increase if those out-groups where themselves hostile to the in-group to begin with.

Worldview defense leads to radicalization. This may just be a radicalization of the worldview itself (i.e. a decrease in the willingness to compromise and to seek common ground with alternative worldviews), but it may also be a radicalization in commitment to that worldview – that is, in action. If the (radicalized) worldview is such that it condones violence (in certain circumstances) and hostility towards out-groups also increases, then this may result in acts of violence towards those out-groups – that is, “terrorism”.

Terrorism itself has a number of effects. Most directly, it increases mortality salience for everyone witnessing it, either directly or indirectly through media coverage. The more attention the media pay to an act of terrorism, the more mortality salience increases; and the more people the media reach, the more people will experience an increase in mortality salience. This increase in mortality salience radicalizes different people (through worldview defense) in different ways. Members of marginalized, discriminated groups are more likely to respond with “terrorist” forms of violence (but see below), thus closing the circle. Members of dominant groups are more likely to further marginalize and discriminate the already marginalized and discriminated groups (insofar as they hold those responsible for the act of terrorism). That this radicalization of the socially dominant groups can become very ugly as well was illustrated in August 2016 when French police officers forced an innocent woman to undress in public because she was wearing a burqini.14

The horizontal line from terrorism to discrimination/marginalization in figure 2 represents this indirect effect of terrorism through radicalization of the dominant groups, but that line really summarizes a figure somewhat similar to figure 2. For the socially dominant group, an increase in mortality salience (in response to terrorism) leads to worldview defense and radicalization just as much as it does for marginalized/discriminated groups, but that radicalization leads to “structural violence” rather than “terrorist” violence in case of dominant groups. The notion of structural violence was introduced by Johan Galtung and is best explained by quoting him:

Violence with a clear subject-object relation is manifest because it is visible as action. It corresponds to our ideas of what drama is, and it is personal because there are persons committing the violence. (…) Violence without this relation is structural, built into structure. Thus, when one husband beats his wife there is a clear case of personal violence, but when one million husbands keep one million wives in ignorance there is structural violence. Correspondingly, in a society where life expectancy is twice as high in the upper as in the lower classes, violence is exercised even if there are no concrete actors one can point to directly attacking others, as when one person kills another. (1969: 171)

Structural violence is institutional (or “structural”) discrimination and marginalization. Hence, the structural violence resulting from the worldview defense and radicalization of socially dominant groups towards the already marginalized and discriminated groups that are held to be responsible for terrorism further increasing discrimination and marginalization of those groups.

That members of marginalized, discriminated groups are more likely to respond with “terrorist” forms of violence – as suggested above – does not imply that they necessarily do, of course. Most don’t, and as mentioned repeatedly before, several other factors and circumstances play a role. The main reasons why members of marginalized/discriminated groups are more likely candidates for violent radicalization are twofold. Firstly, they have more reason for hostility towards the out-groups that marginalize and discriminate them (that is, towards the socially dominant groups). And secondly – and much more importantly – marginalization and discrimination lower self-esteem, and that has various further effects. Lower self-esteem leads to more death-related thoughts and thus to a further increase of mortality salience, but it also makes terror management less effective, thus requiring further strengthening of worldview defense. Hence, in comparison to the members of other social groups, the members of marginalized/discriminated groups experience more mortality salience and thus are in need of terror management more, but because of lower self-esteem they have less effective terror management, and therefore, they need much more extreme worldview defense – and thus further radicalization – to make terror management sufficiently effective to restore psychological balance.15

Again, further ingredients are needed for radicalization to take the form of terrorism. European Jews were marginalized and discriminated for centuries, for example, but responded with intellectual and economic productivity rather than with violence. And Black Americans are probably discriminated more than Muslims in Europe, and are certainly subjected to much more (institutional) violence, but seem unlikely to respond with terrorism. There are various differences in circumstances that could explain the difference, and the question which ones of those make the difference is obviously an important one, but is outside the scope of this post.

Figure 2 shows a further relevant effect of terrorism that has not yet been mentioned: retaliation. Often, acts of terrorism leads to further acts of violence towards those held to be responsible. The so-called “war on terror” is an obvious example. But these further acts of violence lead to an increase in mortality salience in the same way as the original “terrorist” act of violence did. And because of that, violent retaliation may help a terrorist organization more in its recruitment efforts, than that it damages it.

There is nothing new or original in this post. Everyone with a serious interest in terrorism and radicalization could – and probably should – be familiar with all of the above. This doesn’t appear to be the case, however, with one important exception. That exception is ISIL/ISIS/Daesh. Some of the writings of that organization suggest that they are very much aware of the psychological aspects of terrorism, and particularly of those described in this post, and even that they base aspects of their strategy on this insight. In other words, ISIL/ISIS/Daesh appears to have a better understanding of key aspects of human psychology, and makes more effective use of that understanding, than its enemies.

Those enemies are the governments and societies of the countries targeted by ISIL/ISIS/Daesh and its affiliates. These include Western countries, but also many countries in Africa and Asia. Especially Western governments respond to terrorism in the worst possible way. Violent retaliation only further increases mortality salience. And further marginalization and discrimination of Muslim minorities only promotes radicalization. The aforementioned incident of French police officers forcing a Muslim woman to undress in public is the best propaganda ISIL/ISIS/Daesh could get, and it is hard not feel that the French collectively deserve the wave of terrorism that they will have brought upon themselves with this stupidity. But no one deserves to be a victim of terrorism, of course. (Just as much as no one deserves to be a victim of discrimination and/or marginalization.)

One final question that needs to be addressed here concerns the nature of this Western “stupidity”. As mentioned, while ISIL/ISIS/Daesh seems to have quite a sophisticated understanding of psychology, Western governments appear to be completely ignorant. There are three possible explanations for this “stupidity”.

(1) They are completely ignorant indeed. That is, Western governments overlook some essential scientific theory and data, and as a consequence only manage to add fuel to fire.

(2) It is ideological blindness. As explained above, dominant groups respond with worldview defense (and radicalization) just as much as marginalized groups do, and worldview defense includes a tendency to deny or invalidate any idea or evidence that does not fit in that worldview. If the radicalized worldview of the dominant groups tends towards a simplistic blaming of the others’ culture or religion (that is, blaming Islam for terrorism), then alternative theories and evidence for alternative explanations will just be discarded.

(3) The third possibility is that the ignorance is merely apparent, and that Western governments are making use of the psychological processes described above towards their own ends (and thus that they are consciously and intentionally promoting radicalization). Worldview defense strengthens in-group identification, but also the acceptance of the dominant values and beliefs of that in-group and of its social and political arrangements. This in turn, leads to blindness for injustices caused by (or even in) the in-group, and a decreased willingness to criticize that in-group (and its leaders). In other words, radicalization of the socially dominant groups in a society makes the members of those group more conservative, more nationalistic, more obedient, and less critical. This is, of course, all very useful from the perspective of the ruling elite.

This third possibility is the “evil option”, but I doubt that it plays a significant role in explaining the “stupidity” of Western governments. Most likely that is explained by a mixture of ignorance and ideological blindness (i.e. options 1 and 2). But the result of this ignorance and ideological blindness is that Western governments are helping ISIL/ISIS/Daesh and its affiliates more than fighting it.

Much the same is true for the mass media, of course. Their extensive coverage of both terrorist violence and retaliatory violence only increases mortality salience, and the simplistic blaming of Islam that has become increasingly common only leads to further marginalization and radicalization. Like Western governments, the Western media appear to be completely ignorant of the psychological processes involved in terrorism, and the possible explanations of this apparent ignorance are very similar as well. The “evil option” would be that terrorism sells and thus that the media profit from promoting terrorism, but a combination of the other two options, ignorance and ideological blindness, seems a more plausible explanation.

Regardless of what explains the “stupidity” of the Western response to the terrorism of ISIL/ISIS/Daesh and its affiliates, it is rather scary to realize that the terrorists are smarter than their enemies. So much smarter, in fact, that their enemies effectively become their allies, because everything those “enemies” do to fight the terrorists only helps the terrorists, and every “victory” against some particular terrorist group becomes a Pyrrhic victory in a war that cannot be won – or not in this way, at least.

references

- Becker, Ernest. 1973. The Denial of Death. New York: Simon & Schuster.

- Burke, Brian L., Andy Martens, & Erik H. Faucher. 2010. “Two Decades of Terror Management Theory: a Meta-Analysis of Mortality Salience Research”, Personality and Social Psychology Review 14.2: 155-195.

- Galtung, Johan. 1969. “Violence, Peace, and Peace Research”, Journal of Peace Research 6.3: 167-191.

- Greenberg, Jeff & Jamie Arndt. 2012. “Terror Management Theory”. In P.A.M. van Lange, A.W. Kruglanski, & E.T. Higgins (Eds.), Handbook of Theories of Social Psychology, Volume one, London: Sage, 398-415.

- Greenberg, Jeff, Linda Simon, Tom Pyszczynski, Sheldon Solomon, & Dan Chatel. 1992. “Terror Management and Tolerance: Does Mortality Salience Always Intensify Negative Reactions to Others Who Threaten One’s Worldview?”, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 63.2: 212-20.

- Hoffman, Buce. 2006. Inside Terrorism. Revised and Expanded Edition. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Kesebir, Pelin & Tom Pyszczynski. 2012. “The Role of Death in Life: Existential Aspects of Human Motivation”. In R.M. Ryan (Ed.), The Oxford Handbook of Human Motivation, New York: Oxford University Press, 43-64.

- Schmid, Alex P. & Albert J. Jongman. 2005. Political Terrorism: A New Guide To Actors, Authors, Concepts, Data Bases, Theories, And Literature. Expanded and Updated Edition. Piscataway: Transaction Publishers.

- Sherman, D.K. & G.L. Cohen. 2006. “The Psychology of Self-Defense: Self-Affirmation Theory”, Advances in Experimental Social Psychology 38: 183-242.

- Solomon, Sheldon, Jeff Greenberg, & Tom Pyszczynski. 2015. The Worm at the Core: on the Role of Death in Life. New York: Random House.

Notes

- For an overview of definitions (and more), see: Schmid, Alex P. & Albert J. Jongman. 2005. Political Terrorism: A New Guide To Actors, Authors, Concepts, Data Bases, Theories, And Literature. Expanded and Updated Edition. Piscataway: Transaction Publishers.

- With obvious exceptions for acts that are merely called “terrorism” by political opponents and that really have have nothing to do with terrorism.

- See, for example, Hoffman, Buce. 2006. Inside Terrorism. Revised and Expanded Edition. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Becker (1973). For short introductions into TMT, see Greenberg & Arndt (2012) or Kesebir & Pyszscynski (2012). For a non-academic, book-length introduction, see Solomon, Greenberg Pyszczynsky (2015).

Becker, Ernest. 1973. The Denial of Death. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Greenberg, Jeff & Jamie Arndt. 2012. “Terror Management Theory”. In P.A.M. van Lange, A.W. Kruglanski, & E.T. Higgins (Eds.), Handbook of Theories of Social Psychology, Volume one, London: Sage, 398-415.

Kesebir, Pelin & Tom Pyszczynski. 2012. “The Role of Death in Life: Existential Aspects of Human Motivation”. In R.M. Ryan (Ed.), The Oxford Handbook of Human Motivation, New York: Oxford University Press, 43-64.

Solomon, Sheldon, Jeff Greenberg, & Tom Pyszczynski. 2015. The Worm at the Core: on the Role of Death in Life. New York: Random House. - It usually does the latter in two complementary ways. Firstly, being part of something that lives on – and especially “living on” in the memories of others who are part of the same “thing” – promises “symbolic immortality”. Secondly, virtually all religions (and religion is a key aspect of any civilization) promise an afterlife, and thus “literal immortality”.

- Solomon, Greenberg & Pyszczynsky (2015): 211.

- Greenberg & Arndt (2012): 403.

- Burke, Brian L., Andy Martens, & Erik H. Faucher. 2010. “Two Decades of Terror Management Theory: a Meta-Analysis of Mortality Salience Research”, Personality and Social Psychology Review 14.2: 155-195: p. 187.

- See Solomon, Greenberg & Pyszczynsky (2015) for an overview of empirical evidence for all the aspects of TMT.

- Greenberg, Jeff, Linda Simon, Tom Pyszczynski, Sheldon Solomon, & Dan Chatel. 1992. “Terror Management and Tolerance: Does Mortality Salience Always Intensify Negative Reactions to Others Who Threaten One’s Worldview?”, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 63.2: 212-20.

- A smoker who considers being a smoker an essential part of her identity will only strengthen her commitment to that identity – and thus to smoking – in response to an increase of mortality salience. Because of this effect, some anti-smoking campaigns are unlikely to be effective

- Except in worldviews that have tolerance and compassion as key values. See previous note.

- Source (in Dutch). Accessed on August 30th, 2016.

- A burqini is a swimsuit for Muslim women that covers everything except the face.

- This process is further strengthened by a need for self-esteem or self-affirmation independent from the indirect path through mortality salience. See Sherman & Cohen (2006). This is represented in figure 2 with the direct line from lower self-esteem to the need to raise self-esteem.

Sherman, D.K. & G.L. Cohen. 2006. “The Psychology of Self-Defense: Self-Affirmation Theory”, Advances in Experimental Social Psychology 38: 183-242.