Seven years ago I published a paper arguing against afterlife beliefs and various other kinds of “death denial” titled “The Incoherence of Denying My Death”.1 The denial of death in this sense is not a denial of physical or biological death so much as it is a denial of annihilation. In that paper I distinguished two ways of denying death, which are distinguished essentially by which word in the short proposition “I die” they deny. Strategy 1 denies the dying part – that is, it argues that I somehow (can) survive my physical/biological/bodily death. Strategy 2 denies the “I” in “I die” – that is, it argues that because in some relevant sense I don’t exist anyway, the “I” in “I die” doesn’t really refer to anything.

Superficially, it may seem that Buddhism opts for strategy 2 and all (?) other religions for strategy 1, but that is a mistake. Buddhism does indeed hold that in some sense there is no self or I, but doesn’t deny the phenomenal (experienced, conventional) self, and it is that I that dies. Because it is undeniable that I exist in some sense – even if merely as an illusion – I die in some sense, and thus strategy 2 is incoherent.2 Strategy 1 doesn’t fare any better, however.

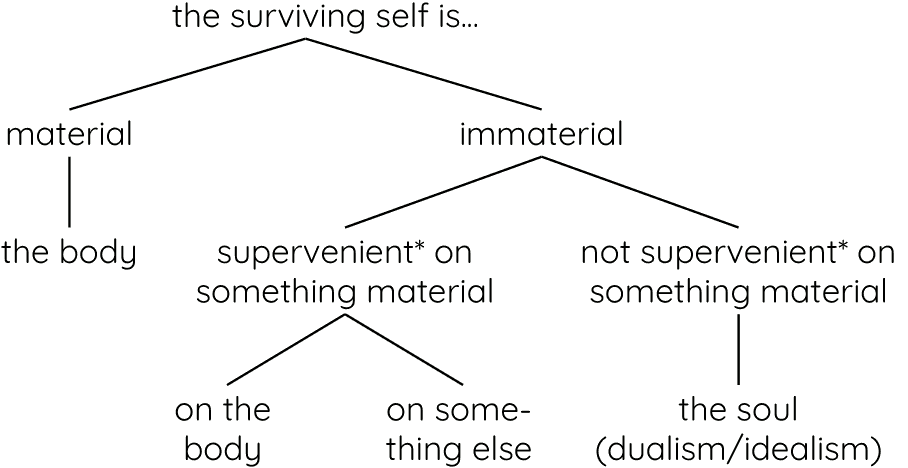

Strategy 1 isn’t really a single strategy, but a cluster of related strategies that all claim that somehow something that is essentially me survives my physical/biological/bodily death. What distinguishes these variants is what that surviving “something” is. Logically, there aren’t that many options. All of them are shown in the following diagram, but that diagram does require some explanation.

The “thing” that survives my physical/biological/bodily death – let’s call it the surviving self – is either material or immaterial. There are no further options.3 If it is material then the only interpretation that makes sense is that it is my brain or body. In other words, if I survive my apparent bodily death, then my body or brain doesn’t really die. So-called “Christian materialists” believe something like this.

The “thing” that survives my physical/biological/bodily death – let’s call it the surviving self – is either material or immaterial. There are no further options.3 If it is material then the only interpretation that makes sense is that it is my brain or body. In other words, if I survive my apparent bodily death, then my body or brain doesn’t really die. So-called “Christian materialists” believe something like this.

If the surviving self is immaterial, then there are again two options: either it is supervenient from, or ontologically dependent on, or emergent from (or something similar) something material or it isn’t. In the first case, the most obvious idea is that the self (regardless of whether it survives) is supervenient* on the body or brain.4 The self (or mind, but I’ll ignore that distinction here), then, is something like software running on the brain (i.e. the hardware). The alternative is that is supervenient* on something else, but it is rather difficult to make sense of that option, and in the aforementioned paper I argue that Mark Johnston’s attempt to argue for something like that fails.5

The final, and historically most important option, is that the surviving self is not supervenient* on something material, but is independent thereof. In that view, the surviving self is something like a soul or spirit. This view again comes in two varieties (which isn’t shown in the figure). If you hold that there are material things in addition to immaterial souls/spirits/minds, then you are a substance dualist. If, on the other hand, you hold that there are no material things and that everything is in the mind, then you are a metaphysical idealist.

This exhausts the possibilities – there are logically no further options to deny annihilation, just minor variants of the options mentioned – and for most of these “options”, Mark Johnston already showed that they are incoherent in his book Surviving Death, so all I had to do in my paper was to refute Johnston’s escape and strategy 2. However, my paper explicitly excluded technological immortality – it’s focus was on theories that deny death rather than on techniques to negate it, and that omission I want to address here. (So, after this very long introduction, we’re finally starting to get to the point.)

As far as I can see, there are two hypothetical forms of technological immortality, and both fit in the diagram shown above. The first is a sub-variant of the “supervenience* on the body” branch: it builds on the mind/self-as-software analogy and suggests that that software can be downloaded an installed on some new hardware if the current hardware (i.e. the body/brain) fails. The second is a sub-variant of the material/body branch: it suggests that medical technology might develop to a point that death is no longer a biological necessity. Let’s look at these two options in turn.

When I was a kid, we had a Commodore 64 computer at home. At school we learned (very!) basic programming on an Apple II; one of my friends had a ZX Spectrum; and other friends had other computers again. Software wasn’t interchangeable, but was specific to these different computer systems, so I couldn’t exchange a program that ran on the Commodore 64 with the friend who used a ZX Spectrum, and so forth. With the current ubiquity of Microsoft Windows, it is easy to forget that software doesn’t automatically run on any piece of hardware. Rather, it has to be written for a specific type of hardware.

Perhaps, minds (and selves) can be compared to software and the brain to hardware, but every piece of hardware (i.e. every brain) is unique, and every piece of software – that is, every mind – runs on just that piece of hardware. Moreover, it isn’t the case that the “software” is written and designed for particular hardware configurations, but rather, the software and hardware develop together, and the software continuously changes the hardware. (And it is largely for this reason that every brain is unique.) Unlike computers, brains are not independent from the “software” that runs on them – in the contrary, in response to everything your mind does and experiences, your brain changes. Hence, the supposed “hardware” isn’t very “hard” at all, and unlike in case of computer systems, there is no sharp boundary between “software” and “hardware”. The processes in the brain and the (physical) brain architecture are not two independent things like computer software and hardware, but an integrated, interdependent, and co-evolving whole.

A key implication hereof, of course, is that the idea of “downloading” a mind is nonsensical. The only way you could “download” your mind like a piece of software and run it on some other system is if that other system would have an architecture identical to the piece of “hardware” you are using now – that is, identical to your brain. Perhaps, this is possible in principle, but at the current state of technology, we are nowhere near realizing anything remotely like that. (We can neither map a brain’s architecture with sufficient precision, nor make computers with brain-architecture-like qualities.) And most likely, rather than designing a new piece of “hardware” that copies the one you are using now, it is probably much easier to make sure that the “hardware” you are using doesn’t fail, which brings us to the second option.

That second option doesn’t aim for a replacement “body”, but for improvements in medical technology that make it possible to continue to live in this body. There is ongoing research on stopping or even reversing aging in humans. Perhaps, gene-therapy can establish something like that, or nano-robots, or some other (new) technology or combination of technologies. There doesn’t seem to be any fundamental reason why such technological immortality is impossible. If medical science and technologically advance sufficiently, we might be able to live forever.

Well, … no. We won’t live forever for a number of reasons. Firstly, it’s unlikely that this kind of technology will be sufficiently developed in our life time. Secondly, it’s unlikely that climate change will be halted in time to allow for much (if any) scientific progress in the second half of this century and afterwards. (More likely, we’re steering for societal collapse.) And thirdly, we won’t be able to afford it.

If this kind of technological immortality becomes a possibility, it will come at a price, and consequently, immortality will only be available to the very rich. Now, take a minute consider the injustice implied in that. Social inequality is already bad enough, but at least we are all equal in one respect: we all die. Technological immortality would radically change that – the super-rich get to live forever, while the rest of us must die – and it is hard to predict the social consequences thereof.6 We are already disposable – how much more so will be in the eyes of a member of the immortal elite? Effectively, the current class divide (which has already been widening) would turn into a divide of species, and in the same way that we tend to disregard the interests of ants, the immortals will probably disregard the interests of the disposable untermenschen (subhumans) that is the rest of us. But unlike ants, the disposables have brains – we may be seen as zombies from the elite point of view, but we aren’t brainless, and unlike ants (but a bit like zombies) we can revolt.

If technological immortality becomes a possibility, I expect that – unless it will be made available to all7 – some mortals will try to assassinate the immortals. (And no nano-robots or gene-therapy will protect them from assassination.) Given that the number of mortals will almost certainly far exceed the number of immortals, this is very likely to succeed. Technological immortality, then, would take the hubris of the elite just a little bit too far – like Icarus flying too close to the sun – resulting in their downfall.

This, of course, is science fiction. In all likelihood we’ll never face this scenario because climate-change-driven collapse will halt pretty much all scientific progress at some point in the current century. The main point here is that – as far as we can see now – there appears to be no fundamental (bio-medical/technological) reason why some kind of technological immortality would be impossible. Whether it would be practically possible and achievable, and whether it would be morally desirable is another matter.8

supplemental note (June 17th)

Recent research published in Nature Communications suggests that technological immortality may be harder to achieve than I suggested above. I wrote that “there doesn’t seem to be any fundamental reason why such technological immortality is impossible” (in reference to medical/technological life-extension methods), but Fernando Colchero and a long list of co-authors indicate that there actually might be a fundamental reason why such technological immortality would be difficult at the very least least (and perhaps even impossible). “Can we humans slow our own rate of ageing?” they ask near the end of their paper. Their cautious reply is that “it remains to be seen if future advances in medicine can overcome the biological constraints that we have identified here, and achieve what evolution has not”.9

If you found this article and/or other articles in this blog useful or valuable, please consider making a small financial contribution to support this blog, 𝐹=𝑚𝑎, and its author. You can find 𝐹=𝑚𝑎’s Patreon page here.

Notes

- Lajos Brons (2014). “The Incoherence of Denying My Death”, Journal of Philosophy of Life 4.2: 68-89.

- Obviously, there is a bit more to it than this, but for the full argument you’ll have to read my aforementioned paper.

- Assuming that “immaterial” means “not material”. Sometimes, something like quasi-materiality is suggested, but no one has been able to make sense of such an intermediate between the material and the immaterial.

- The asterisk denotes that it isn’t exactly clear whether this really is supervenience or emergence or some other kind of ontological dependence, but that really doesn’t matter.

- Mark Johnston (2010). Surviving Death (Oxford: OUP).

- Additionally there are also obvious demographic consequences of immortality, especially if the technology would ever become cheaper and more widely available.

- Which would lead to a demographic disaster.

- The latter is not unimportant, as immortality might undermine all ethics. Nothing really matters if you live forever.

- Fernando Colchero et al. (2021). “The Long Lives of Primates and the ‘Invariant Rate of Ageing’ Hypothesis”, Nature Communications 12.3666, p. 6.