There are Buddhisms for all four cardinal directions: Southern Buddhism, Northern Buddhism, Eastern Buddhism, and Western Buddhism. Southern Buddhism is the Buddhism practiced in Sri Lanka, Myanmar, and Thailand. The term “Northern Buddhism” either covers everything else, or only refers to the Buddhism practiced in Tibet and Mongolia. In the latter case, Eastern Buddhism is the Buddhism found in Taiwan, Korea, Japan, China, and Vietnam. In the two-way North/South distinction, India is part of Northern Buddhism. In the three-way North/South/East distinction, on the other hand, India is missing, indicating that this isn’t a classification of historical Buddhisms. However, while Buddhism died out in India about a millennium ago, it was revived in the 20th century by B.R. Ambedkar among the dalits (untouchables/outcasts), so the three-way distinction isn’t an accurate classification of currently practiced Buddhism either.1 Western Buddhism, finally, is the Buddhism practiced in “the West” (Europe, North America, Australia), but it must be noted that Western Buddhism is almost never mentioned together with the other three geographical designations.

The two-way North/South distinction and the three-way North/South/East distinction aren’t merely geographical categorizations, but are also associated with sects, schools, or traditions within Buddhism. Southern Buddhism is Theravāda. In the two-way distinction, Northern Buddhism is either everything else, or Mahāyāna plus Vajrayāna. (“Everything else” also includes extinct sects of “mainstream” Buddhism (derogatorily called Hīnayāna), such as Sarvāstivāda, Sautrāntika, and so forth.) In the three-way distinction, Northern Buddhism is Vajrayāna and Eastern Buddhism is East-Asian Mahāyāna. Hence, the three-way distinction omits Indian Mahāyāna and other extinct sects and currents. (The omitted dalit Buddhism in India is Navayāna, by the way.)

Contrary to the other three geographical designations, Western Buddhism is not associated with a school, tradition, or broad current of Buddhism. This is an important difference and is probably one of the reasons why Western Buddhism is almost never mentioned together with the other three. A related difference is that for the other three, Buddhism in the relevant geographical area is more or less synonymous to Southern/Northern/Eastern Buddhism – that is, “Buddhism in Tibet and Mongolia” is virtually synonymous to “Northern Buddhism”. However, “Buddhism in the West” is not synonymous with “Western Buddhism”. A Jōdō Shinshū temple in London and a Tibetan temple in Tasmania would be examples of Buddhism in the West, but not (necessarily) of Western Buddhism.

As mentioned, Southern, Northern, and Eastern Buddhism are not merely geographical designations. They also refer to school affiliations and particular lineages and traditions within Buddhism, as well as to their cultural backgrounds and contexts. The term Western Buddhism also refers to cultural background and context, of course, but does not pick out school affiliation or lineage, and doesn’t denote a (recognized) tradition. While this is a fundamental difference, one may wonder whether the difference is largely due to time. Maybe 16 or 17 centuries ago, Eastern Buddhism was quite similar in this sense to Western Buddhism now. Maybe Western Buddhism is just an immature tradition or a proto-tradition, like Chinese Buddhism was then. Whether Western Buddhism will ever mature into a new Buddhist tradition is an open question, of course – it can only be answered in a few centuries from now (if civilization survives the climate crisis). And this obviously also implies that it can only be decided in the future whether current Western Buddhism is (or then was) an immature tradition indeed. Nevertheless, I think that this is a much more useful and charitable way of looking at Western Buddhism than the more typical perspectives.

Even if Western Buddhism evolves into a new tradition within Buddhism, this doesn’t mean that it would become homogeneous, of course. Northern and Eastern Buddhism consist of many schools and sects, and even though all of Southern Buddhism is Theravāda, there is significant variety within that tradition as well. Moreover, the proto-traditions that these three traditions developed from were even more heterogeneous – they consisted of many competing and intermingling currents and tendencies, none of which survives. The three Buddhist traditions were formed in internal and external dialog and debate. Currents and tendencies coexisted in the same monasteries and weren’t (initially) organized in separate sects. Scholar-monks defended ideas and practices against competing ideas and practices within Buddhism (even within the same monastery), but also against non-Buddhist ideas and practices, such as Brahmanism in India, Daoism and Confucianism in China, and Bon in Tibet. In this process, ideas were sharpened, clarified, and improved, leading to the eventual rise of new currents and tendencies, but also – sometimes – to the incorporation of non-Buddhist ideas.

四恩 si-en is a good example of the latter. The term refers to four kinds of obligations, namely to the Buddha, to one’s parents, to the state or ruler, and to other people.2 This is an essentially Confucian idea transformed into an Eastern Buddhist doctrine. It’s “Buddhist” source is the second chapter of Dasheng bensheng xin di guan jing 大乘本生心地觀經 (T159), which is traditionally considered to be a Chinese translation of a lost Indian sūtra, but which was – according to Tsukinowa Kenryū – actually composed in Chinese by a 9th century Afghan monk named Prajñā.3 This is but one example of how traditions formed and changed in the interaction with their cultural and intellectual environments, and it is largely for this reason that there are such big differences between Chinese, Japanese, Tibetan, Sri-Lankan, and other Buddhisms. 四恩 si-en is not even the most prominent example of an adaptation of Eastern Buddhism to its cultural surroundings – that honor goes Buddha-nature doctrine, which became a dominating and defining feature of the Eastern tradition.

While it is possible to distinguish tendencies and currents within Western Buddhism, these are not really comparable to early sects and currents in the Indian or Chinese proto-tradition. This may be mostly due to another very important difference. In the various proto-traditions, ideas were developed, promoted, and defended by highly accomplished scholar-monks supported by networks of monasteries. Western Buddhism, however, is an almost exclusive non-monastic, lay phenomenon. There are no Western Buddhist monks or monasteries. (There are Western monks and Western monasteries, but those belong to sects of non-Western Buddhism.) And consequently, there are no Western Buddhist scholar-monks and doctrinal/philosophical debates between them either. There are relevant debates among (mostly academic) scholars of Buddhism, of course, but there is a chasm between their work and lay Buddhist practitioners, while scholar-monks and other monks lived in the same monasteries and practiced together. Because of this, the tendencies that can be recognized within Western Buddhism differ from the currents that existed in the various proto-traditions.

In the non-Western proto-traditions, different currents or sects coalesced around points of (philosophical) doctrine and/or the monastic rules. Important sects or currents in early Chinese Buddhism include Dilun 地論 and Sanlun 三論, for example. The former was based on a variant of Yogācāra; the latter on Madhyamaka. However, they weren’t mere transplants of Indian Yogācāra and Madhyamaka to China, but Chinese developments thereof. Their Indian sectarian roots were transformed in the interaction with Chinese philosophical and cultural concerns. There are very few currents within Western Buddhism that are comparable to Dilun and Sānlùn in this respect. Western Zen and Soka Gakkai International (SGI) might come closest, although I’m much more uncertain about the second than about the first. Both appear to have deviated significantly from their Japanese parents in response to Western cultural concerns. (That both have Japanese origins is probably a coincidence.) For (most?) other sects and currents found in the West this is not really the case, or to a far lesser extent. Moreover, most of Western Buddhism is so fragmentary and individualistic that it can even be argued that it cannot be meaningfully divided into different sects at all.

Neither Dilun nor Sānlùn survives – both disappeared many centuries ago. And all of the sects of Eastern Buddhism that do survive have essentially East-Asian roots. They are not transplants of Indian sects or schools, but new developments that grew in Chinese and Japanese soil (mainly). There isn’t anything like that in Western Buddhism (yet). Secular Buddhism appears to be a mostly Western development, even though it has Asian precursors, but lacks doctrinal coherence and organization and can, therefore, not be compared to Chan/Zen 禪or Tiantai/Tendai 天台, for example.

Arguably, the lack of something like a monastic order hinders the kind of scholarly/philosophical debates that gave rise to the various ideas and sects that formed the Buddhist traditions. What would be necessary for the development of a Western Buddhist tradition is serious, sustained engagement by scholarly inclined Buddhists with the Western intellectual tradition(s) (and of non-Buddhist Western thinkers with Buddhism), and – outside academia – this is happening insufficiently. And even if it would be happening, the lack of something resembling a monastic (and inter-monastic!) organization hampers the spread of ideas, which is essential for their testing and refinement.4 Furthermore, in the Buddhist (proto-) traditions, the monastic order also performed another essential function, namely, that of gate-keeping. By keeping out people who’s ideas deviated too much or who merely sought monastic status because they expected to profit from it, the monastic order prevented dilution into nothingness. Lacking monastic organizations, Western Buddhism has no good defense against such threats. (The mindfulness industry may be a threat in exactly this sense.)

Taking all of this into account, one may wonder whether Western Buddhism is even a proto-tradition (or immature tradition). At best, it seems to be at a stage even before that – an infantile tradition, perhaps? It must not forgotten, however, that there are very significant differences between the current sociopolitical and economic context and that of the time periods in which Indian, Southern, Eastern, and Northern Buddhism developed. It would be a bit odd to expect that – given these vast differences – the paths towards maturity would be exactly the same. Perhaps, there are other “things” (in a very broad sense of “thing”) that could foster debate and provide the necessary guard rails. Nevertheless, regardless of whether there are, no path to maturity can start without serious, sustained engagement between Buddhism and the Western intellectual and cultural tradition(s).

To what extent current tendencies within Buddhism can facilitate that engagement, or are more likely to be a hindrance, is open for debate. (But I’m inclined to say that it is probably the latter.) As mentioned, these “tendencies” in Western Buddhism have little in common with the doctrine-based currents and sects found in the other proto-traditions. They are related to non-Buddhist influences and aspects of the broader cultural environment and are not really based on different ideas about doctrine and/or practice (although they have implications with regards to those). Furthermore, it is not entirely correct to speak of “adherents” or “followers” of these tendencies either for two reasons. First, these tendencies are mostly unconscious influences on practitioners/believers of Western Buddhism. And second, in most cases, individual practitioners/believers will be influenced by several of these tendencies, and the exact mix of influences/tendencies (and how that mix works out) differs from person to person. Furthermore, the tendencies are not homogeneous and in combinations of tendencies they interact, creating further variants.

The four main tendencies are (associated with) modernism, the New Age, neotraditionalism, and neoliberalism. The first two arose in the 19th century; the third was a 20th century response to the first two; and the fourth was a more or less independent development of the final decades of the 20th century. It must be noted that, aside from the New Age, these tendencies are not exclusively Western, although this may be partially due to Western influence on the rest of the world. However, while Western and non-Western forms of these tendencies are related, they are not identical. The New Age doesn’t seem to have any significant influence outside the West. Although there are New-Age-adjacent movements in Japan that have been intermingling with esoteric Buddhism, these movements have very different roots than the Western New Age, however. In addition to these four tendencies, there is a number of “attitudes” that is relatively common among Western Buddhists, such as orientalism, exoticism, and anti-intellectualism. These aren’t as multi-faceted and complex as the four tendencies, but awareness of their occurrence and effects may be equally important. The following table summarizes some of the key features of the four tendencies. A slightly more detailed description will be given below the table. After that, I will very briefly discuss the aforementioned attitudes.

| Modernist | New Age | Neotraditional | Neoliberal | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| authority | scripture | individual | sect/teacher | individual |

| doctrine | rationalist; attempts to reconstruct the historical Buddha’s original teaching | spiritual perennialist; mainly based on New Age ideas with a cherry-picked sprinkling of Buddhism | (varies between sects) | de-emphasized: focus on “useful” practice; dukkha as merely mental/psychological |

| proximate goal | (unclear) | self-improvement | merit for good rebirth | stress-relief, happiness |

| ultimate goal | (unclear) | becoming one with the universe, higher consciousness | awakening/enlightenment | (none) |

the Modernist tendency

Buddhist modernism arose in the 19th century in Sri Lanka, Japan, and the West. It is often suggested that Buddhist modernism in Asia had Western origins, but I think that there is an (orientalist?) tendency to significantly overestimate Western influence.5 Asian Buddhist modernism (and its history/origins) are of limited relevance here, however, so let’s focus on its Western variants.6

If Western Buddhist modernism had a birth date, this would be November 10, 1844. On that day French Buddhologist Eugène Burnouf published the first volume of his Introduction à l’Histoire du Buddhisme Indien (Introduction to the history of Indian Buddhism) in which he depicted the historical Buddha as an undogmatic, rational, and very human thinker.7 This demythified (or “disenchanted”) and rationalist version of the Buddha became the central figure of Buddhist modernism. When Heinz Bechert introduced the latter notion, he argued that Buddhist modernism emphasizes the rational elements in Buddhist thought, increases attention to this-worldly affairs, and increases the role of the laity.8 While Bechert was writing about Sri Lanka mainly, the same applies to Western Buddhist modernism, although there are some subtle differences. Most obviously, lacking a Buddhist monastic tradition, the emphasis on the laity is even greater in the West, but perhaps even more important is that Western Buddhist modernism is even more rationalist than its Asian sisters.

Ceylonese (or Sri-Lankan) Buddhist modernism has been called “Protestant Buddhism” by Gananath Obeyesekere (and others) due to another common feature of Buddhist modernism that it shares with (Christian) Protestantism: a strong orientation towards a kind of text-based, “authentic” Buddhism.9 Like the rationalist aspect, the scripturalist aspect of modernism is even stronger in the West as well, which may be related to the much more direct influence of Protestantism. For example, Gregory Schopen has pointed out that early Buddhology was heavily influenced by Protestantism from which the field inherited a number of methodological assumptions. He wrote that: “The methodological position frequently taken by modern Buddhist scholars, archaeologists, and historians of religion looks, in fact, uncannily like the position taken by a variety of early Protestant reformers who were attempting to define and establish the locus of ‘true religion’”.10 But it is not just Western academic Buddhologists who were influenced by Protestantism – very many Western Buddhists come from Protestant backgrounds as well. (For more on the notion of “Protestant Buddhism”, see my previous post with that title.)

While it could be said that Western Buddhist modernism was born in 1844, it did take half a century before it started to take off. What triggered this was Paul Carus’s The Gospel of Buddha, published in 1894.11 Before that, Buddhism in the West was mostly a subject of academic study, but after Carus’s book, Western interest in Buddhism started to grow significantly. And the kind of Buddhisms that took off in the West tended to be very “Protestant” indeed.

Key features of the modernist tendency are rationalism and scripturalism, but these aren’t weighed identically by all “modernists”, and these features also work out a bit differently in different combinations with (aspects of) the other tendencies. A prioritization of scripturalism – especially in combinations with (aspect of) the neotraditionalist tendency – tends to lead to fundamentalism. A prioritization of rationalism, on the other hand, tends to lead to so-called “secular Buddhism”. It is often assumed that the latter is a relatively recent Western invention, associated mostly with the work of Stephen Batchelor.12 but this assumption is mistaken, although there are no direct links between earlier secular Buddhisms in Asia and its reinvention in the West. The term “secular Buddhism” was coined in Japanese (世間仏教) by Inoue Enryō 井上圓了, the father of Japanese Buddhist modernism, in 1887,13 and the Sky-Blue sect, which was founded in the 1980s in Myanmar by U Nyana, is another interesting example of Asian secular Buddhism predating its recent Western sibling(s).14 However, while these Asian precursors typically downplay or set aside “non-secular” aspects of Buddhism, some varieties of Western secular Buddhism go much further: they embrace some kind of naturalism and reject all supernatural (or otherwise non-scientific) aspects of Buddhism. There is little consistency in this regard, however, especially in combinations with the New Age tendency, which substitutes a lot of unscientific New Age woo for Buddhist supernatural doctrines. Moreover, many nominal secular Buddhist have beliefs that conflict with a scientific worldview without realizing that this is the case due to insufficient knowledge or understanding of relevant science, or due to an inability to distinguish real science from woo masquerading as science.

(Secular Buddhism is a recurring topic in this blog. See the tag “Secular Buddhism”.)

the New Age tendency

The New Age tendency also dates to the 19th century, but remained mostly under the surface until fairly recently. Historically, there are links between New Age Buddhism, Theosophy, and Buddhist modernism, mostly because of the association of Henry Steel Olcott and Anagarika Dharmapāla with all three. Olcott was a co-founder of the Theosophical Society and officially converted to Buddhism in the 1880s. His book A Buddhist Catechism (1881) is much more modernist than New Age, however.15 While the influence of the New Age on Western Buddhism can hardly be overstated, this tends to remain relatively invisible in texts. Probably, the reason for this is that the New Age influence tends to be far greater on less erudite Western Buddhists. Based on my own experience in various internet forums (so this is a bit speculative), it seems (to me) that there is an inverse relation between understanding of Buddhism (and of science) and New Age beliefs. And because books and articles tend to be written by people who have a least some understanding of their topic, New Age Buddhism isn’t very common in writing. It is also for this reason that the New Age tendency remained mostly under the surface until fairly recently (as I wrote a few sentences back): the advent of the internet has given New Age Buddhists a voice, or many voices, and many of those are very loud.

Since I have recently posted a long article on New Age Buddhism, I will not say much about this tendency here. For details, see that article. Here, I will merely summarize some of the key features of New Age Buddhism.

- Individualism. — The highest authority in the New Age is oneself. Truth is subjective, and there is no authority on matters of belief and practice other than the individual themself.

- Perennialism and eclecticism. — There are, according to the New Age, many common themes and ideas in different religions and philosophical systems, which reflect and reveal universal truths about the nature of reality and more. Because of this, elements from various belief systems can be freely combined. New Age Buddhists often do not clearly distinguish Buddhism from Hinduism, for example, or between Buddhism and Stoicism. (On the latter, see also my post on pop-Stoicism.)

- Anti-realism and holism. — New Agers tend to believe that we create (our) realities with our thoughts. New Age holism includes a belief in the interconnectedness of all things, but also a rejection of various “dualism”, such as the dualism between the spirit/mind and matter/nature. Often, the universe is conceived of as some kind of cosmic consciousness, life force, or “energy”, and a common goal of New Age practice is “becoming one with the universe”.

- Buddha nature vs. No-self. — New Age Buddhism rejects the doctrine of no self (or reinterprets it so radically that this effectively is a rejection as well). Commonly (but not always) the rejection of no-self is supported with an interpretation of Buddha nature doctrine, but there are also New Age/Buddhist/Hindu hybrids that adopt (interpretations of) Hindu views of the self.

- Wellbeing. — New Age practice is aimed at achieving mental and physical wellbeing in this world. More distant/ultimate goals of practice are often conceived of as “achieving a higher state of consciousness” or “becoming one with everything”.

It should go without saying that none of these features of New Age Buddhism are actually Buddhist. However, the influence of New Age Buddhism is so overwhelming in some parts of the internet that many people are no longer capable of distinguishing the two. Furthermore, despite the fact that the New Age worldview is thoroughly unscientific (and the New Age was originally anti-science), its adoption of pseudo-science, quasi-scientific terminology (“energy”, “quantum”, etc.), and attempts to construct scientific-sounding supports for its doctrines has made it quite difficult for casual observers to distinguish real science from New Age woo. Because of this, the combination of the New Age tendency with nominal secular Buddhism (i.e., the most rationalist branch of the modernist tendency – see above) is surprisingly common. I suspect that a very substantial percentage of people who consider themselves “secular Buddhists” are more accurately classified as New Agers. However, no research has been done about this, so this suspicion is merely based on personal observations.

the Neotraditionalist tendency

Neotraditionalism is a 20th century response to modernism and the New Age. Neotraditionalists see modernist or Western elements in, or influences on Buddhism as inauthentic corruptions (even though they might not necessarily use these terms) and aim to adopt the doctrines and practices of a particular sect or school of traditional Buddhism. “Aim” is italicized here, as Western Buddhist followers of some variety of traditional Buddhism do not always have a sufficiently clear picture of the doctrines and practices of a particular sect. (Perhaps, the most obvious example of this is Zen. In the Western image, Japanese Zen Buddhism is all about meditation; in practice, it is mostly concerned with funeral rites, and many Japanese Zen priests rarely meditate. And pre-modern Japanese Zen monks spent much more time studying than meditating.) Furthermore, there is a very obvious friction between neotraditionalism and monasticism: real traditional Buddhism is monastic, but among Western Buddhists – even those with neotraditionalist leanings – the choice to become a monk or nun is relatively rare.

In general, neotraditionalists accept the authority of their teacher and the sects they adhere too, which is a major difference with the previous two tendencies (with reason and scripture as the supreme authorities for modernists, and subjective individual authority for New Agers). But despite this fundamental difference combinations of the neotraditionalist tendency with the aforementioned two tendencies in not uncommon at all. Neotraditionalism plus modernism often leads to some kind of fundamentalism (usually Theravāda fundamentalism) or to an attempt to reconstruct (or reinvent) so-called “early Buddhism”, which is – supposedly – the Buddhism that existed in the lifetime of the Buddha (and/or very shortly thereafter). Alternatively, neotraditionalism with rationalist/secular (rather than scripturalist) modernism is most common among adherents of Western Zen, who often seem to believe that traditional Zen Buddhism doesn’t strictly require belief in karma, rebirth, and other doctrines that are problematic from a secular/naturalistic point of view. Neotraditionalism mixed with New Age tends to fly a bit more under the radar, but is not at all uncommon among nominal Tibetan Buddhists – that is, Western Buddhists who self-identify as adherents of Tibetan Buddhism, but whose understanding of the latter is heavily influenced by New Age beliefs.

the Neoliberal tendency

The neoliberal tendency within Western Buddhism came up in the last quarter of the twentieth century under the influence of hegemonic neoliberalism. From neoliberal culture, it inherited a strong individualism and an (even stronger?) focus on usefulness (or expected “benefits”). Because of the latter, neoliberal Buddhism tends to downplay doctrine. “Buddhism is just a practice” is a common credo among neoliberal Buddhists. That practice, moreover, is entirely aimed as stress relief and/or improving mental wellbeing/happiness and ditches more traditional goals of Buddhist practice such as awakening.

In After Buddhism, Stephen Batchelor writes that he does not seek “to arrive at a dharma that is little more than a set of self-help techniques that enable us to operate more calmly and effectively as agents or clients, or both, of capitalist consumerism”,16 but as Slavoj Žižek has pointed out, neoliberal Buddhism is pretty much just that. According to Žižek, Western Buddhism is the “perfect ideological supplement” to capitalism,17 because its “meditative stance is arguably the most efficient way, for us, fully to participate in capitalist dynamics, while retaining the appearance of sanity.”18 Žižek sees Buddhism as a “fetish”, that is, as a tool “to cope with harsh reality”. A fetish allows people “to accept the way things are – because they have their fetish to which they can cling in order to defuse the full impact of reality.”19 And thus,

when we encounter a person who claims he is cured of any beliefs, accepting social reality the way it really is, one should always counter such claims with the question: “OK, but where is the fetish that enables you to (pretend to) accept reality ‘the way it really is’?” “Western Buddhism” is such a fetish: it enables you fully to participate in the frantic pace of the capitalist game, while sustaining the perception that you are not really in it, that you are well aware how worthless this spectacle really is – what really matters to you is the peace of the inner self to which you know you can always withdraw …20

The failure of some varieties of Western Buddhism to be much more than self-help is also illustrated by its most common defense by adherents when facing criticism: “it works for me”. That’s apparently all that matters: that it “works” for me (or that it “benefits” me) in better coping with the stresses caused by this world. Furthermore, this defense simultaneously illustrates the individualist focus of neoliberal Buddhism – what matters is that it works for me.

Although doctrine tends to be relatively unimportant in the neoliberal tendency, it does have some key doctrines. One of these is the idea that Buddhism is all about accepting things as they are. Suffering isn’t caused by things outside our mind, but by how we respond to those things. According to pop-Stoicism, we should just accept what we cannot control (namely, what is outside the mind), and focus on what we can control (namely, how we respond or react). This idea, which is really a corruption of Stoicism, has little to do with Buddhism (and is based on very shaky foundations, moreover), but variants of it are frequently presented as Buddhist doctrine by neoliberal Buddhists. We cannot control pain, but suffering (which – in this view – is caused by how we respond to that pain) is “optional”, adherents of this doctrine sometimes proclaim. So, we should stop worrying about what according to the doctrine is outside our control, and mold ourselves into a state of stress-free acceptance.

An interesting illustration of the second (but not unrelated) key doctrine of neoliberal Buddhism is James Deitrick’s accusation that engaged Buddhists are forgetting “the most basic of Buddhism’s insights, that suffering has but one cause and one remedy, that is, attachment and the cessation of attachment”.21 The crux of this doctrine is a reduction of suffering or dukkha to one specific variety thereof. Traditionally, three kinds of dukkha are distinguished. The most basic kind is physical and mental pain (which may even include dissatisfaction, annoyance, boredom, and fatigue). The second, more subtle kind of dukkha derives from change and the impermanence of things (in the broadest possible sense of “thing”) – any gain, any achievement, any satisfaction, any positive sensation or emotion, and so forth only lasts for a brief while, leading to unhappiness and craving for more after it has drained away. The third, even subtler kind of dukkha results from the fact that this change and impermanence is fundamentally outside of our control because everything is interdependent (or “conditioned”). Nothing is permanent and nothing is independent (of causes, conditions, and other things) – including we, ourselves. Dukkha in this third sense, sankhara-dukkha, is related to existential dread, but also to a general dissatisfaction resulting from the fact that things never are (or can be) as we expect and want them to be. Neoliberal Buddhism disqualifies the first two kinds of suffering and identifies dukkha with sankhara-dukkha. Consequently, pain and worldly suffering are irrelevant to Buddhism, and Buddhism is exclusively concerned with the kinds of mental/psychological suffering associated with sankhara-dukkha.

Both of these doctrines are ideology in the sociological sense of that term: they serve the interests of whoever profits from the status quo. Neoliberal Buddhist are expected to accept things as they are – including injustice, poverty, and oppression – and just focus on their own mental wellbeing because (a) Buddhism is all about acceptance, and (b) Buddhism isn’t concerned with injustice, poverty, oppression and other kinds of worldly suffering anyway. (It doesn’t take much knowledge of Buddhist thought and the history of Buddhism to realize that both doctrines are false, but that doesn’t matter here.)

The New Age and neoliberal tendencies share an individualist focus, suggesting an obvious combination, but because of neoliberalism’s cultural hegemony, almost all Western Buddhists are influenced by the neoliberal tendency. The only exceptions – as far as I can see, at least – are those Western Buddhists that are conscious of the corrupting influence of neoliberal cultural hegemony and that are actively fighting this influence (in their own thought as well as that of others), but that appears to be a very small minority. Many nominal secular Buddhists seem to be particularly strongly influenced by the neoliberal tendency, which may be partially due to Batchelor’s influential interpretation of Buddhism in terms of “reactivity”, which is very close to the aforementioned neoliberal Buddhist doctrine of acceptance.

attitudes – orientalism, exoticism, anti-intellectualism

As mentioned above, in addition to these four “tendencies”, there are a few other characteristics that are commonly (but not universally!) found among Western Buddhist and that further interact with the tendencies. I called these “attitudes” above. The most important are orientalism, exoticism, anti-intellectualism.

- Orientalism is a kind of othering that opposes the West to the East, simultaneously defining both, by characterizing the East as irrational, childish, erotic, feminine, weak, conservative/backward, and so forth, and the West as the Enlightened opposite of all that. In the context of Western Buddhism, one common expression of orientalism is the sentiment that (originally pure and rational) Buddhism has been corrupted in Asia by all kinds of irrational/ritual accretions. Orientalism is probably most common in the modernist tendency, where traditional Buddhism (i.e., mainstream Asian Buddhism) is often looked at with disdain, and where Asian cultures are sometimes considered to be irrational and backward.

- Exoticism is similarly dependent on stereotypes of non-Western (mostly Asian) cultures, but more or less fetishizes the perceived difference. Where orientalism uses negative stereotypes of the East to define itself in (positive) opposition to that, exoticism selectively idealizes and fetishizes some perceived qualities of the Eastern other. Eastern cultures are seen as offering something that is considered missing in Western culture. However, this “something” is typically (commercially and otherwise) exploited in a way that satisfies Western interests, without taking the interests of non-Western cultures (or even the cultural context of this “something”) into account. Exoticism is very common in New Age Buddhism, but neotraditionalists also often have exoticist leanings.

- Anti-intellectualism is a very widespread aspect of American culture and has strongly affected some strands of Western Buddhism. The most common expression of anti-intellectualism is the assertion that “Buddhism is just a practice”. Anti-intellectualist adherents of Western Buddhism typically believe that no significant study of Buddhist thought is necessary and are often even hostile or scornful towards people who are more knowledgeable in this regard. The parable of Nan-in and the Professor is often appealed to in an attempt to support this arrogant anti-intellectualism (without realizing, of course, that these anti-intellectual dilettantes are themselves analogous to the “professor” with the over-full cup in the parable). Anti-intellectualism is most closely associated with the neoliberal tendency, but is also found in the New Age tendency and in (nominal) secular Buddhism.

What could a (more) mature Western Buddhism be like?

Thus far I have focused primarily on describing current Western Buddhism, but what I actually find much more interesting is what a (more) mature Western Buddhism – if that will ever evolve – could be like.

A major complication with regards to the notion of a Western Buddhism – especially if that term is to denote a (future) tradition within Buddhism – is that the terms “Western” and “modern” are sometimes used interchangeably, implicitly suggesting that these terms mean roughly the same thing, or that being modern implies being Western and the other way around. This implicit identification of “modern” and “Western” appears to be (unintentionally) racist or orientalist. If “modern” effectively equals “Western” or the other way around, then this implies that what is non-Western is pre-modern,22 or in other words, primitive. Hence, the Western/modern identification is at least somewhat problematic, but this identification also raises an important question: How can we distinguish “Western” aspects from “modern” aspects in Buddhism?

I already mentioned above that Buddhist modernism isn’t just Western and has been very influential in South and East Asia. Furthermore, although it is often claimed that Asian Buddhist modernism has Western origins, I have seen little evidence for substantial direct Western influence on twentieth-century developments in Asian Buddhist thought. It is sometimes suggested that Western scholarship played an important role, but that is probably an exaggeration as well. The writings by Japanese academic Buddhologists and scholar-monks like Yinshun 印順 (China/Taiwan) were much more widely read and certainly much more influential than those by any Western author. Hence, an identification of Western Buddhism with Buddhist modernism fails for two reasons: First, as already pointed out above, modernism is merely one tendency within Western Buddhism. And second, Buddhist modernism is also Asian.

The term “Western” (or “the West”) denotes a civilization, culture, or family of cultures. The term “modern” (or “modernity”) either denotes a developmental stage of a civilization or culture, or functions to emphasize relative newness and/or a contrast with the traditional. (Notice that the aforementioned identification of “Western” and “modern” suggests that only Western civilization has reached and can reach the developmental stage of “modernity”, at least by itself, which supports the suggestion that this identification is racist.) “Modernity” as a historical period starts in the 16th (or even 15th) century and ends some time in the 20th century, but this not exactly the same notion of “modern” that matters here. In the context of Buddhism (and religion in general), I don’t think that modernity has ended yet, for example.

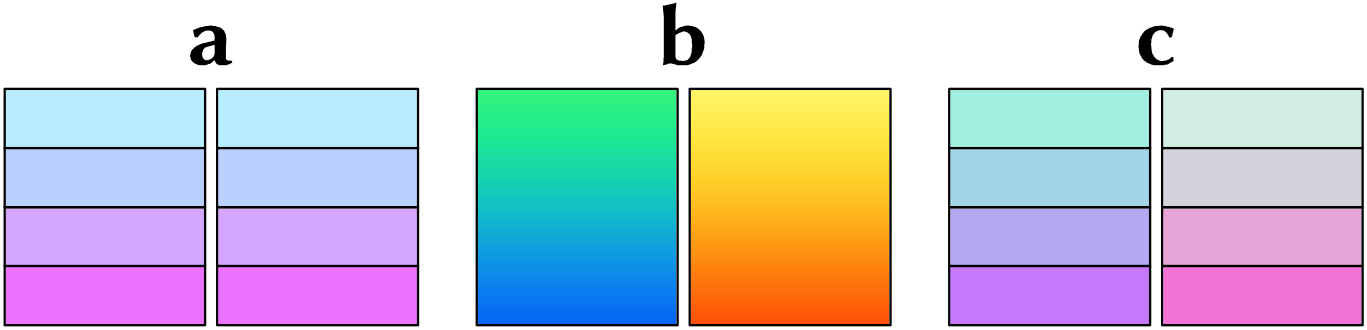

With regards to the historical development of civilizations (like Western civilization, Chinese civilization, and so forth) we can make a rough distinction between three kinds of basic models illustrated in the figure below. In that figure, the two columns under “a”, “b”, and “c” represent two different civilizations, while the vertical axis represents time.

In model a, the two civilizations pass through the exact same developmental stages. They may not do so at the same times, but the basic features of these various stages are essentially the same. Perhaps, the best illustration of this model is Friedrich Engels’s Der Ursprung der Familie, des Privateigentums und des Staats (1884, The Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State),23 or at least some orthodox Marxist interpretations thereof. Model b is the other extreme – in this model there are no stages at all, and the two cultures just have entirely different historical developments. Model c is – more or less – a compromise between these two extremes: there are historical stages, and different civilizations pass through these stages in roughly the same order, but how these stages work out exactly differs from civilization to civilization depending on particular circumstances and historical trajectories.

In model a, the two civilizations pass through the exact same developmental stages. They may not do so at the same times, but the basic features of these various stages are essentially the same. Perhaps, the best illustration of this model is Friedrich Engels’s Der Ursprung der Familie, des Privateigentums und des Staats (1884, The Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State),23 or at least some orthodox Marxist interpretations thereof. Model b is the other extreme – in this model there are no stages at all, and the two cultures just have entirely different historical developments. Model c is – more or less – a compromise between these two extremes: there are historical stages, and different civilizations pass through these stages in roughly the same order, but how these stages work out exactly differs from civilization to civilization depending on particular circumstances and historical trajectories.

Both a and b seem nonsensical to me. There is too much variety between cultures and civilizations to make a plausible, but on the other hand, there obviously are developmental stages related to agriculture, pottery, metallurgy, economy, and so forth that occurred all over the world, so b cannot be right either. Something like c, then, seems the most plausible approach. In that approach, modernity (or something very much like it) would be a stage that all civilizations can reach, but that would nevertheless differ between (i.e., work out differently in different) civilizations. What significantly complicates the picture, however, is that Western civilization seems to be the only civilization that reached modernity by itself, and consequently, that it has become nearly impossible to distinguish aspects of some local, non-Western modernity (if those exist) from imported Western modernity. In case of figure c, we can study the purple, bottom stage 4 in either civilization by comparing it, on the one hand, with stage 3 in that same civilization, and on the other hand, with stage 4 in the other civilization. In this way, it becomes possible to distinguish what is characteristic of that stage from what is characteristic of that civilization. In case of modernity, however, this is exactly what we cannot do, as one version of modernity has been exported to all other civilizations before they could develop their own. (Asuming that modernity is a stage in the sense of figure c, of course.)

What we might be able to do, on the other hand, is zoom in at specific supposed features of either modernity or Western culture and assess when and how they arose. If a feature arose relatively recently and in response to something that isn’t inherently Western, moreover, then it it is not a plausible feature of Western culture specifically. This doesn’t imply it is necessarily “modern”, of course, as there are further options.

Take individualism as an example. It is often assumed that individualism is an aspect of Western culture(s), and indeed, on most measures, Western cultures appear to be more individualistic than non-Western cultures. However, when I looked into this over two decades ago in the context of my PhD research, I found a correlation between individualism and wealth (on the spatial level of countries) with a time gap of several decades, strongly suggesting that wealthier countries eventually become more individualistic,24 and more recent research summarized by Yamagishi Toshio suggests that individual Japanese are just as individualist as Westerners, but that this individualism is tempered in some contexts by cultural expectations.25 Furthermore, Western individualism also seems to be only a few centuries old, and individualist notions such as autonomy and (individual) rights are closely associated with modernity. Hence, while it certainly can be said that individualism is part of modern Western culture, it is (probably!) not inherently Western.

An emphasis on practical usefulness or benefit doesn’t seem inherently Western either, even if it is a widespread feature of current Western culture. I don’t think that this characteristic is modernist either – it seems to be of more recent date. It might be associated with the growing cultural impact of capitalism throughout the 20th and 21st centuries. It might also be associated with American culture. (It is no coincidence that pragmatism as a school of Western philosophy is very much of American origins.) This latter suggestion points at something else that is essential to keep in mind: “Western” doesn’t equal “American”. While American culture has become extremely influential, there is more to the West than the USA, and there are many aspects of American culture (such as the aforementioned anti-intellectualism, but also the strong emphasis on usefulness) that are far less prominent or even absent elsewhere in the West.

The more I thought about other possible features of Westernity/modernity to more clearly distinguish what is “Western” from what is “modern”, the more I started to think that this may not be the right approach to understanding what Western Buddhism could be(come). So, let’s go back to the comparison with the infancy of Chinese Buddhism. No Indian sect thrived or even survived in China, and even Chinese sects that were related to Indian sects (such as Dilun and Sanlun mentioned above) eventually gave way to indigenous Chinese sects. Whether, due to different circumstances, Asian sects have a better chance of surviving in the West than Indian sects once had in China remains to be seen (but I doubt that they do). What’s more important here is the nature of the indigenous Chinese sects relative both to Chinese culture and to Indian Buddhism. Without going into detail, I think it is safe to say that the Chinese remodeled Buddhism in at least three interrelated ways:

(1) Change of language and associated conventions. — Indian Buddhist texts were translated into Chinese, but more important is that new text were written by Chinese Buddhists. There texts were written in Chinese and in a style that is typically quite different from that of Sanskrit or Pāli texts. There are differences in the flow of arguments, in the way of presenting them, in metaphors, in rhetorical styles, and so forth. Paul Swanson, who translates Chinese Buddhists texts into English and who is fluent in English and Japanese, has observed that one cannot really give the same talk in those two languages, and that there are no one-to-one correspondences between words in different languages.26 Switching from one language to another (except if they are closely related, perhaps) is also a stylistic switch, a switch in styles of reasoning and presentation, and – to some extent, at least – a switch in ways of thinking. Since the main language of Western Buddhism is English (rather than Pāli, Sanskrit, Chinese, or Japanese), it is to be expected that this leads to similar shifts in argumentative style, presentation, and ways of thinking as those that occurred in Chinese Buddhism some 17 centuries ago. This change is already visible in Buddhist text written by Western authors, but I don’t think it’s significance is fully appreciated.

The underlying logic of Western ways of writing is natural deduction. The more a text deviates from customary patterns of valid argument, the less comprehensible it tends to be, from a Western point of view, at least. While similar patterns and forms can also be observed in Indian or Chinese writing (modus tollens is extremely common in classical Chinese philosophy, for example), there also are differences. Some argument forms that are common in one tradition are uncommon or even absent in another, and there are other stylistic and rhetorical differences. Indian arguments tend to rely much more on analogy, for example, and metaphor seems to play a much bigger role in Chinese texts. Differences like these are products of different thinking styles and conventions, and such differences influence whatever is thought about.

(2) Engagement with indigenous philosophical traditions. — Chinese Buddhism developed in a continuous dialogue, confrontation, and comparison with indigenous traditions such as Daoism and Confucianism. Originally, Buddhism was explained in Daoist terms and there is a very significant influence of Daoism on Chan/Zen especially. It seems to me that Confucian influence was initially more subtle (but see the example of 四恩 si-en discussed above), but in the past few centuries, neo-Confucian ethics seems to have almost completely replaced Buddhist ethics within the Buddhism of most East-Asian sects and schools.

I don’t think that it can be reasonably predicted what a hypothetical mature Western Buddhism would gain from its engagement with Western philosophy and Western thought in general. In case of China, it took a few centuries of conversation between Buddhism and Chinese thought before an indigenous Chinese Buddhism developed, and I don’t think that anyone at the beginning of that process could have predicted what the end result would be. What is important to understand, however, is that Chinese Buddhist philosophy from the 4th century or so onward is as much Chinese philosophy as it is Buddhist philosophy. Presumably, the same would be the case for a future Western Buddhist philosophy: it would be Western philosophy as much as Buddhist philosophy.

(3) Cultural recontextualization. — Buddhism originated in a cultural environment characterized by widely shared beliefs in karma, a cycle of death and rebirth (saṃsāra), and the ultimate goal of escaping that cycle through mokṣa/nirvāṇa. None of these beliefs – or anything like them – were part of the Chinese cultural environment, and consequently, it not at all surprising that these aspects of Buddhism were very much de-emphasized in Chinese Buddhism. Western Zen Buddhists like to point out the relative unimportance of karma and rebirth in Zen, but Pure Land Buddhism is actually a much better example, and is much more influential in East Asian Buddhism, moreover. In Pure Land Buddhism, karma plays no role whatsoever in salvation, which entirely depends on professing faith in some specific Buddha or Bodhisattva (usually Amitābha). And the cyclicity of death and rebirth is (mostly) ignored: after death, the believer is reborn in the paradise-like Pure Land. The latter (i.e., rebirth in the Pure Land) is the goal, and nirvāṇa is almost forgotten, or even considered impossible in the current era of 末法 (Ch. mofa; Jp. mappō). Karma and (cyclical) rebirth are probably even more alien to Western culture than they were to ancient Chinese culture, so I think that it is very unlikely that these would play any (significant) role in a future Western Buddhism. That doesn’t mean that they would be explicitly denied as in secular Buddhism – they could just be mostly ignored as in much of East Asian Buddhism.

Another example of how Buddhism changed due to different cultural circumstances is Buddha nature theory, which (in one version) holds that every sentient being has the capacity of (eventually!) becoming a Buddha. (“Buddha nature”, in this theory, is nothing but the capacity of becoming a Buddha.) While the theory has Indian roots, it evolved and flourished in China, mainly in response to the Mahāyāna doctrine that icchantika can never achieve awakening. The Chinese, who had a more egalitarian and less stratified view of reality and the living beings in it, rejected this notion in favor of the claim that every sentient being can (eventually) achieve awakening. I don’t think that this example of adaptation of Buddhism to a different cultural context has much relevance for (the future of) Western Buddhism, but given the importance of Buddha nature theory in East Asian Buddhism, it is important to realize that this theory developed in China due to indigenous concerns and preferences. Similarly, an evolving Western Buddhism would almost certainly evolve new perspectives and new theories (on the basis of Buddhist seeds) in response to Western cultural concerns.

The question, of course, is what the relevant cultural concerns could be, which more or less brings us back to the previous question: What are the relevant aspect of Western (as opposed to merely modern) culture? The West, of course, is not homogeneous and not culturally stagnant, which makes it even harder to answer this question. The aforementioned four “tendencies” are modern Western responses to Buddhism based on modern Western concerns and culture, but there is little reason to believe that the particular concerns and cultural perspectives that gave rise to these tendencies will remain features of Western civilization for centuries to come, which leads to another question:

Can Western Buddhism outgrow its “infantile” stage?

It took several centuries for Chinese civilization to germinate an indigenous Chinese Buddhism. How many centuries exactly is hard to say as it is difficult to pinpoint exact starting and end points of the process, but anything below three centuries is surely unreasonable, and double that sounds a lot more plausible. During this period, a very large number of translators and scholars contributed to the evolution of Chinese Buddhism, and – at least as important – there were many opponents of Buddhism criticizing Buddhist thought (and practice) from the perspectives of various Chinese philosophies (necessitating defensive replies, and thereby further development of Chinese Buddhist thought).

The current situation with regards to Western Buddhism is obviously very different. The network of scholars is fairly small and largely detached from the communities of followers of Western Buddhism. Critical and constructive engagement between Buddhist thought and the Western traditions is a tiny and one-side research field with most contributions (often implicitly) proclaiming the superiority of Buddhism (and very few studies taking the opposite point of view). What may be even more important, however, is that we live in a very different world than that of the ancient Chinese. The current world is vastly more interconnected and the speed of information exchange is orders of magnitudes greater than it was even a century ago. If some of the relevant advantages of our age (like these) could sufficiently compensate for the disadvantages (like those mentioned), then maybe, just maybe, some kind of Western Buddhism could (eventually) evolve, but only if the social conditions remain sufficiently fertile for Western Buddhism to thrive.

There are good reasons to be at least somewhat skeptical about the latter, however. Currently, most climate scientists expect that we’ll reach an average global warming of more than 2.7°C some time in the second half of the current century, which would be absolutely devastating. (But which also seems a bit optimistic. Based on my own research, if find 3 to 4°C more plausible.) Large parts of Africa, Central America, South Asia, Southern Europe, China, the Middle East, and more will probably become so inhospitable that they can no longer sustain large populations.27 Many of the people living there now will either die or try to leave. There will be hundreds of millions of climate refugees (according to most estimates), many of which travel substantial distances, reaching other regions. Rich countries will continue trying to keep those refugees out with walls, fences, and armed guards, but that is doomed to fail when the numbers get this high. These massive migrations and the likely fascist response to them make it improbable that Western culture/civilization survives unscathed.28 Unless we curb our carbon emissions very soon – but we won’t – the second half of the 21st century will almost certainly be characterized by societal and economic collapse, civil war, refugee flows, famines, and increasingly apocalyptic “natural” disasters, and the West will not be spared from any of that. Whatever eventually emerges from the chaos resulting from mass migration and socioeconomic collapse is impossible to predict, but it will be something new and not something merely “Western”. But even if Western civilization would somehow be able to survive the climate crisis, the social conditions in the West won’t be particularly hospitable. Tiny and very individualistic minority religions like Western Buddhism are unlikely to survive in times of social chaos.

Speculating about what a hypothetical future Western Buddhism might be like is really quite pointless then – it will unfortunately probably die in its infancy. Perhaps, it is more interesting to speculate about the future of Buddhism during and after the global catastrophe that is coming,29 although this might be quite pointless for another reason: it is nearly impossible to predict what the post-apocalyptic world will be like.

If you found this article and/or other articles in this blog useful or valuable, please consider making a small financial contribution to support this blog, 𝐹=𝑚𝑎, and its author. You can find 𝐹=𝑚𝑎’s Patreon page here.

Notes

- One might wonder whether the omission of dalit Buddhism is intentional, and if so, what that means.

- There are some variants of this list. For example, the Three Jewels are sometimes mentioned instead of the Buddha, and one’s dharma teacher may replace other people.

- Tsukinowa Kenryū 月輪 賢隆 (1954), 「般若三蔵の翻経に対する批議」, 『印度學佛教學研究』 4.2: 434–43.

- The “test” for philosophical ideas is argument. A good idea is an idea that survives attempts to refute it. But there can only be such attempts if people are aware of the ideas in question.

- See also: Lajos Brons (2022), A Buddha Land in This World: Philosophy, Utopia, and Radical Buddhism (Earth: punctum), pp. 61–2.

- On Buddhist modernism in general, see: David McMahan (2008), The Making of Buddhist Modernism (Oxford: Oxford University Press).

- Eugène Burnouf (1844), Introduction à l’Histoire du Buddhisme Indien, Vol. 1 (Paris: Imprimerie Royale).

- Heinz Bechert (1966), Buddhismus, Staat und Gesellschaft in den Ländern des Theravāda-Buddhismus: Grundlagen. Ceylon (Berlin: Metzer).

- Gananath Obeyesekere (1970), “Religious Symbolism and Political Change in Ceylon”, Modern Ceylon Studies 1: 43–63. See also: Richard Gombrich & Gananath Obeyesekere (1988), Buddhism Transformed: Religious Change in Sri Lanka (Princeton: Princeton University Press).

- Gregory Schopen (1997), Bones, Stones, and Buddhist Monks: Collected Papers on the Archaeology, Epigraphy, and Texts of Monastic Buddhism in India (Honolulu: University Of Hawai‘i Press), p. 13.

- Paul Carus (1894), The Gospel of Buddha (Chicago: Open Court).

- Stephen Batchelor (1997), Buddhism without Beliefs: A Contemporary Guide to Awakening (New York: Riverhead). Batchelor (2011), Confessions of a Buddhist Atheist (New York: Spiegel & Grau). Batchelor (2015), After Buddhism: Rethinking the Dharma for a Secular Age (New Haven: Yale University Press). Batchelor’s papers on the topic are collected in: (2018), Secular Buddhism: Imagining the Dharma in an Uncertain World (New Haven: Yale University Press).

- Inoue Enryō 井上圓了 (1887),『仏教活論序論』, in:『井上円了選集』(Tokyo: Tōyō University 東洋大学), vol. 3: 327–93, p. 388.

- Hiroko Kawanami (2020), “The Making of an ‘Inside Enemy’: A Study of the Sky-Blue Sect in Myanmar”, Buddhism, Law, & Society 6: 1–40. Niklas Foxeus (2024), “The Doctrine of the Sky-Blue One in Myanmar: Disenchanted Buddhism”, Religion 1–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/0048721X.2024.2408540.

- Henry Steel Olcott (1881), A Buddhist Catechism: According to the Canon of the Southern Church (Colombo: The Theosophical Society).

- p. 17.

- Slavoj Žižek (2006), The Universal Exception (New York: Continuum), p. 252.

- Ibid., p. 253.

- Ibid., pp. 253–4.

- Ibid., p. 254.

- James Deitrick (2003), “Engaged Buddhist Ethics: Mistaking the Boat for the Shore”, in: Christopher Queen, Charles Prebish, & Damien Keown (eds.), Action Dharma: New Studies in Engaged Buddhism (London: RoutledgeCurzon): 252-69, p. 263. Italics in original.

- As there is no other way of being non-modern than being pre-modern. The only apparent third option is post-modernity, but that is really nothing but a minor variety within modernity, and even if that wouldn’t be the case, one would have to be modern first to be able to be(come) post-modern.

- Friedrich Engels (1884), Der Ursprung der Familie, des Privateigentums und des Staats: im Anschluß an Lewis H. Morgans Forschungen, MEW:21, pp. 25-173.

- Lajos Brons (2005), Rethinking the Culture-Economy Dialectic, PhD Thesis (Groningen: University of Groningen)

- Yamagishi Toshio 山岸 俊男 (2015), 『「日本人」という、うそ: 武士道精神は日本を復活させるか』 (Tokyo: ちくま文庫).

- Paul Swanson (2018), “Dry Dust, Hazy Images, and Missing Pieces: Reflections on Translating Religious Texts”, in: In Search of Clarity: Essays on Translation and Tiantai Buddhism (Nagoya: Chisokudō): 213–32.

- Mark Lynas (2007). Six Degrees: Our Future on a Hotter Planet, (Harper Collins), p. 213.

- Christian Parenti (2011). Tropic of Chaos: Climate Change and the New Geography of Violence (Nation Books), p. 20.

- Considering that most of the Buddhist majority countries are expected to be among the countries that will be affected most by climate change, this future isn’t looking very promising either.